Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

19 Apr, 2023

| Local ordinances and reach codes restricting natural gas use in buildings have been a major part of California's drive to phase out fossil fuel heating and became a leader in electric heat pump adoption. Source: welcomia/iStock/Getty Images Plus via Getty Images |

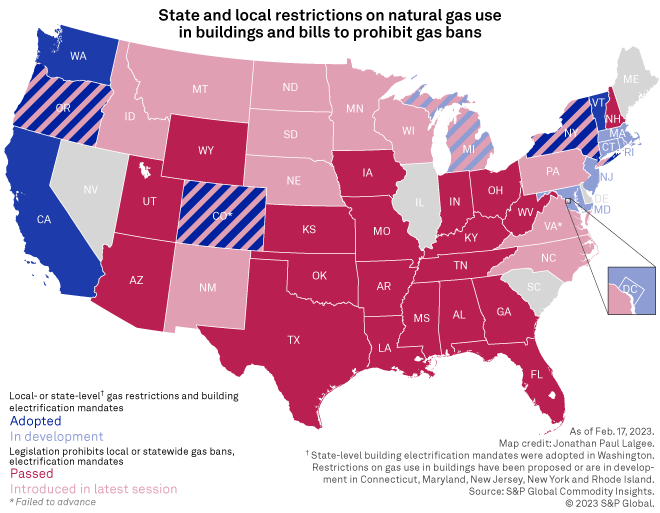

A US appeals court decision that struck down Berkeley, Calif.'s pioneering ban on natural gas use in new construction will likely have limited immediate impacts on a nationwide building electrification movement, though the long-term repercussions are unclear, according to lawyers.

The decision by a three-judge panel to overturn a district court ruling has raised questions about the legal footing of all-electric building requirements and restrictions on gas use in California and several other states. Those measures have proliferated and evolved since the San Francisco Bay Area kicked off the policy push in 2019.

"I think this is a little bit of a tricky issue," said Sarah Jorgensen, a partner at law firm Reichman Jorgensen Lehman & Feldberg, which represented the plaintiff, the California Restaurant Association (CRA), in the case. "Certainly, the more similar a local ordinance is to what Berkeley passed, the more likely it is to fall within ... the holding of this court."

The US Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit ruled April 17 that the federal Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA), which regulates the energy efficiency and use of consumer products, preempts Berkeley's 2019 gas ban. The first-in-the-nation policy prohibited local officials from issuing a building permit for new construction projects that include gas infrastructure within the building. The policy drew a lawsuit from the CRA, which a district court judge dismissed in 2021.

Berkeley-style bans are limited

Of the 72 California cities, towns and counties that enacted policies restricting gas use in new buildings, only about a dozen followed a model similar to Berkeley's, according to data tracked by S&P Global Commodity Insights through year-end 2022. Some cities, including Berkeley, have adopted multiple approaches.

Many of those jurisdictions will likely stop enforcing those policies, lawyers said. If they do not, a party like the CRA could sue the local government. A city would likely seek to avoid litigation expense if it is clear that its policy is no longer valid following the 9th Circuit decision, Jorgensen said.

The decision only applies to the nine western states and two US territories within the 9th Circuit, including Washington and Oregon. Eugene, Ore., followed the Berkeley model when it passed Oregon's first gas ban in residential construction in February.

Asked whether Eugene would review the ordinance in light of the decision, a representative for the city said election law prevented staff from commenting on the ordinance because it has been referred to a ballot referendum.

It is less clear what the decision — and the legal precedent established by the 9th Circuit's reading of the EPCA — means for other types of policies.

Ruling could have unforeseen impacts

In California, most local and county governments followed a model developed in Menlo Park, Calif., which requires all-electric construction through an amendment to the state's Building Energy Efficiency Standards, known as Title 24. A smaller number follow another Title 24-based approach, developed by local community choice aggregators, which requires new buildings with natural gas hookups to achieve higher energy efficiency performance, which incentivizes all-electric construction.

Episodes of Energy Evolution are available on iTunes, Spotify and other podcast platforms.

Asked whether the restaurant industry will pursue challenges to Title 24-based policies, CRA Vice President of Public Affairs Sharokina Shams could not say what the group's next legal steps would be. "I can certainly tell you that the CRA will continue advocating for restaurants to maintain their access to flame cooking," Shams said.

In Washington, policymakers have included electric space and water heating requirements in updates to statewide commercial and residential energy codes. A recently filed lawsuit alleges the Washington State Building Code Council exceeded its statutory authority when it adopted the amendments in 2022.

Jorgensen said it will take further study and analysis to determine whether the 9th Circuit's reasoning will affect policies that deviate from the Berkeley model. "I think if there was something that was either a ban on gas appliances, a ban on natural gas infrastructure, or something that was effectively operating as a ban, it could potentially be subject to the reasoning of the court," Jorgensen said.

Once the 9th Circuit decision goes into effect, it will immediately apply only to policies modeled after the Berkeley approach, not provisions codified in building energy codes, according to Amy Turner, a senior fellow for the Cities Climate Law Initiative at Columbia Law School's Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.

"It's comparing apples to oranges," Turner said. "I do worry that the 9th Circuit judges' reading of EPCA preemption is overly broad and could have impacts on other state and local policies in ways we haven't foreseen yet."

The court's view of preemption

Turner, who studies the legal context around electrification codes and gas bans and supports those policies, believes that the 9th Circuit's holding was overly broad because it preempts local laws that are "several steps removed" from regulating EPCA-covered appliances. In Turner's view, the EPCA's preemption provision is meant to ensure appliance-makers do not face a patchwork of manufacturing standards across the US.

The panel disagreed with several arguments for a narrow reading of EPCA preemption. It rejected Berkeley's argument that EPCA preemption only applies to regulations that establish standards for appliance design and manufacture, rather than rules governing distribution and access to energy sources. It also dismissed the Biden administration's contention that EPCA preemption applies narrowly to energy conservation standards on covered appliances themselves.

Similarly, the panel said one of the lower court's key holdings — that EPCA preemption is limited to regulations that "directly regulate either the energy use or energy efficiency of covered appliances" — was "divorced from the statute's text."

The panel held that the EPCA preempts local or state regulations that "relate to 'the quantity of [natural gas] directly consumed by' certain consumer appliances at the place where those products are used." The point that the panel stressed is that the EPCA is concerned with consumers' ability to use covered appliances at their "intended final destination" within homes and other buildings.

"So, by its plain language, EPCA preempts Berkeley's regulation here because it prohibits the installation of necessary natural gas infrastructure on premises where covered natural gas appliances are used," the panel said. "In sum, Berkeley can't bypass preemption by banning natural gas piping within buildings rather than banning natural gas products themselves."

Uncertain whether policies satisfy exemption criteria

The panel noted that a subsection of the EPCA's preemption provision addresses building codes, illustrating that its scope extends beyond direct regulation of consumer products. That shows that the US Congress intended for the EPCA to preempt building codes that function as energy use regulations, the panel said.

However, as the court noted, the EPCA includes an exemption to its preemption provision. In states like California that give cities authority to amend building codes, local governments can include standards in their codes that concern energy use and efficiency of EPCA-covered appliances, provided they meet several criteria, Turner said.

To satisfy those criteria, a city would have to give builders options to install EPCA-covered appliances, including gas equipment, Turner said.

Whether the reach codes adopted throughout California satisfy those criteria is uncertain. Representatives for Menlo Park and Bay Area Reach Codes, a collaborative that develops model electrification policies, said they were evaluating the 9th Circuit's findings and seeking to understand the ruling and its implications.

Local and county governments adopted the initial round of electrification reach codes following the 2019 update to Title 24. Cities are now readopting and adapting those reach codes as part of the 2022 update cycle, giving them an opportunity to consider the 9th Circuit ruling, said Matt Vespa, a senior attorney at Earthjustice's Clean Energy Program.

Beyond California, it is not certain that other circuit courts would come to the same conclusion as the 9th Circuit, Vespa said. However, for jurisdictions that want to pursue similar policies, it is probably safer for cities to avoid the Berkeley model and opt for policies focused on whole building efficiency, which discourage but do not prohibit gas use, Vespa said.

"I think the takeaway is there's still plenty of pathways for local governments to still restrict gas in new construction and protect their residents and address the climate crisis," Vespa said.

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.