Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY — Aug 18, 2022

By Joseph Hayes

Ahead of the August PMI release, we highlight three major themes to keep tabs on through six charts: inflation, recession risk and labour market conditions.

Inflationary pressures have eased in recent months thanks to reduced supply-chain frictions and the commodity market coming off the boil. Global monetary policymakers will hope to see the weakening trends in the price and supply-related PMIs continue in August.

However, at the same time, recession risk has stepped up, particularly across the developed world as high inflation curtails demand. Whether these risks materialise into a short and shallow or deep and longer downturn likely hinges on what happens in the labour market.

Resilience in the labour market would keep the window open for tighter central bank policy for longer to control inflation, although policymakers will likely become concerned about the inflationary effect of rising pay pressures should tightness in the labour market and high job vacancies bid up wages, as we're already seeing. We highlight six charts to monitor these three themes.

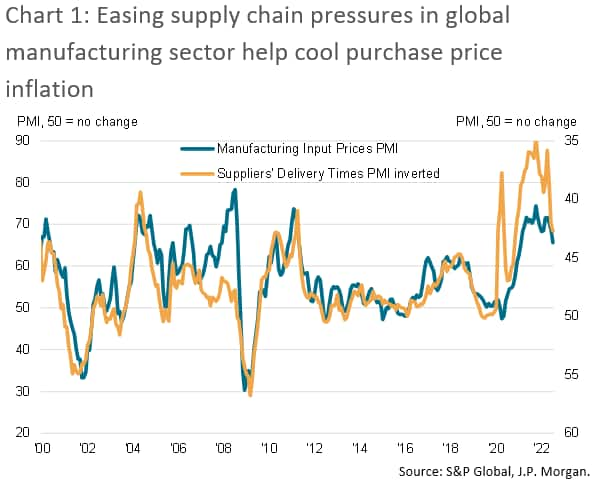

There was growing evidence in July to suggest global price pressures may have passed their peak as the Global Composite Input Prices Index fell to a five-month low. Slower input cost inflation reflected an easing of pressures among both manufacturers and service providers. A key factor which is bringing inflationary pressures down, particularly in the manufacturing sector, is fewer supply constraints (see chart 1).

The Global Suppliers' Delivery Times Index rose to its highest level since November 2020 in July as capacity improvements at vendors, waning demand for raw materials and a reduction in shipping constraints (such as improved capacity at Chinese ports) lessened lead time delays. Worldwide reports of supply shortages were four times their historical average in July (more detail can be found here). While still indicative of considerable supply issues, this marked a third successive drop from around seven times in April.

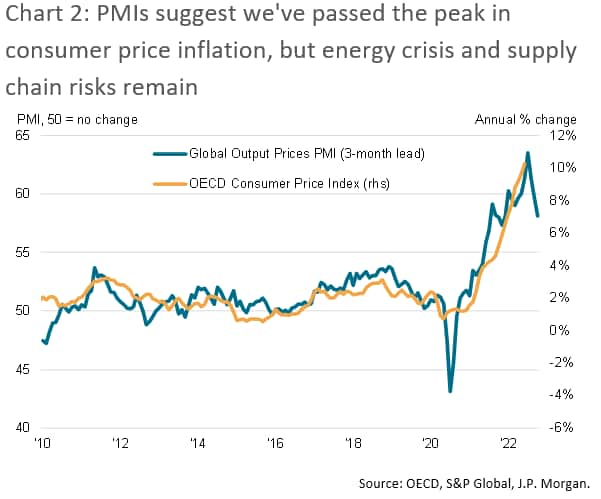

Meanwhile, the Global Composite Output Prices Index fell to its lowest level since September 2021 in July, suggesting that companies are moving their rates charged in line with cost developments and, if input price pressures continue to cool, hints at a further slowing of output price inflation. Comparing the Output Prices PMI with official consumer price inflation among OECD countries suggests a cooling of price pressures in the coming months.

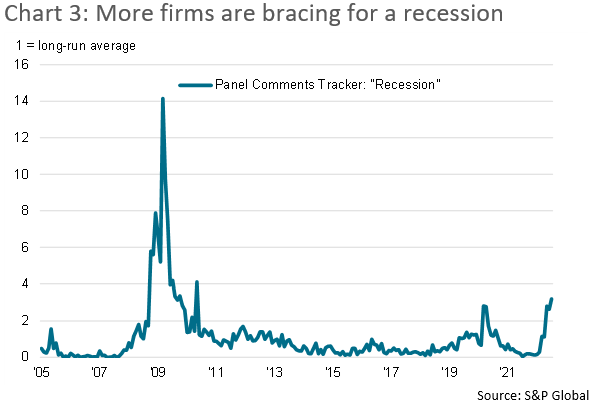

The stark loss of growth momentum, driven primarily by weakness in Europe and the US, suggests the global economy is edging closer to a downturn. With inflation either at or skirting close to double digits and multi-decade highs in many parts of the world, demand conditions showed further signs of slumping in July as new order growth fell to its weakest in two years. Policymakers have made it clear that they wish to raise rates to a level which will reduce demand and in turn, cool inflationary pressures. Surveyed companies signalled growing concern about the prospect of a global recession in July as the number of private sector companies mentioning "recession" was over 3 times its long-run average, a level not seen since the global financial crisis era. More companies citing recession concerns would likely bode ill for the global demand, investment and employment outlook.

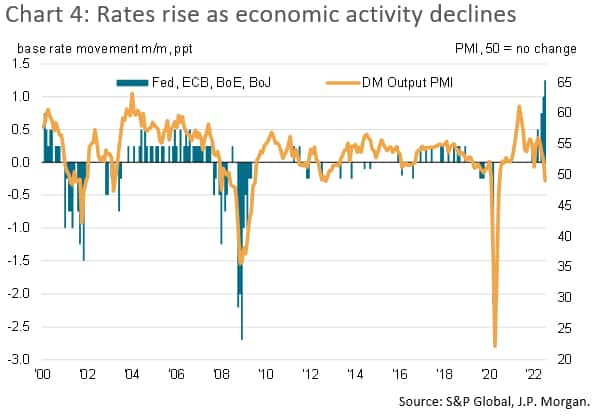

Indeed, while this measure crept up in July, global growth slowed, with the Composite Output Index for developed countries falling to 49.0 and, outside of those seen in the pandemic, signalled the first contraction in business activity since October 2012. The Federal Reserve, European Central Bank and Bank of England have all embarked on policy tightening, but PMI data is in a territory which historically is consistent with policy loosening.

Should a recession materialise, the next question will be whether the downturn is short and shallow or deep and protracted, the answer to which will likely hinge on the labour market.

On the one hand, if we continue to see resilience in employment data, this will likely spur global central banks to maintain course on their aggressive tightening path to bring inflation under control. The Global Composite Employment Index recorded 52.1 in July, above its long-run average (since 1998) of 51.3, signalling relatively robust jobs growth.

Resilience in the labour market will be a welcome sign for monetary policymakers as it should keep the window for rate hikes open for longer, allowing central banks to tackle inflation before a recession hits. That said, a faster unravelling of employment would raise the possibility of a deeper downturn, and potentially drive a pivot back to looser monetary policy, or at least a pause in the hiking cycle.

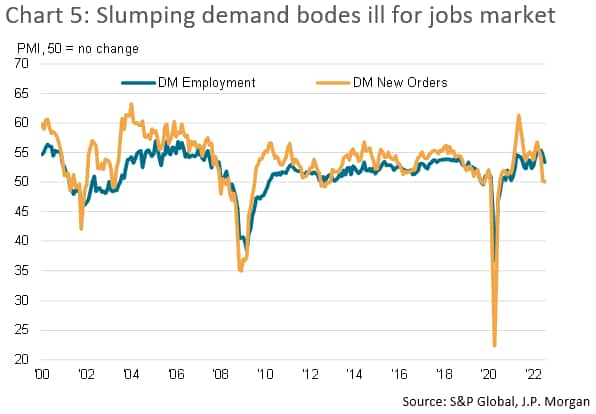

While developed market employment growth slowed in July, comparisons with new orders (see chart 5) suggests this is likely to slow further in August. Weaker jobs market numbers will place central bankers in a position where an aggressive inflation-tackling stance risks raising unemployment and aggravating already-worsening economic conditions. Under this scenario, policymakers may find themselves under pressure to ease policy.

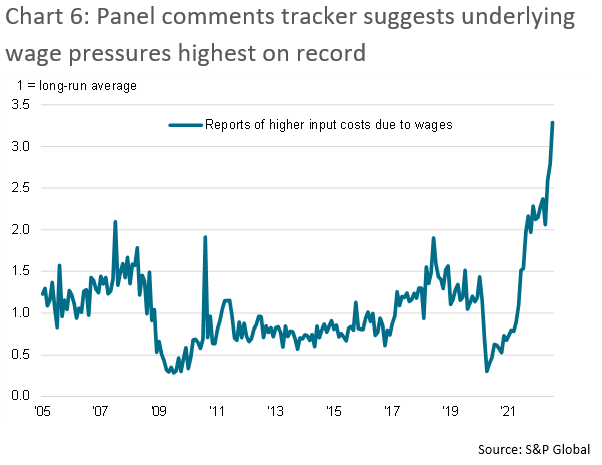

On the other hand, with staff shortages continuing globally, central banks may be wary of nominal wages being bid higher as companies compete for scarce workers. In this scenario, monetary policymakers may be more accepting of rising unemployment. Indeed, according to the panel comments tracker, reports of higher salary costs reached its highest on record (since 2005) in July (see chart 6), signalling strong and accelerating pay pressures globally. With labour market tightness persisting, job vacancies remaining high and workers pushing their employers to raise their wages amid rising living costs, timely indicators of pay pressures will be crucial to watch over the coming months.

Joe Hayes, Senior Economist, S&P Global Market Intelligence

Tel: +44 1344 328 099

joseph.hayes@spglobal.com

© 2022, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.