Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

BLOG — Jun 30, 2021

By Ken Wattret and Venla Sipilä-Rosen

European and Central Asian countries are at the forefront of the rising tide of monetary tightening, with the Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA) region leading the way. Several more central banks will follow, given emerging inflationary pressures and persistent exchange-rate vulnerabilities. We expect monetary tightening in the Europe and EECA region to keep progressing at three differing paces.

Eurozone: Easy does it

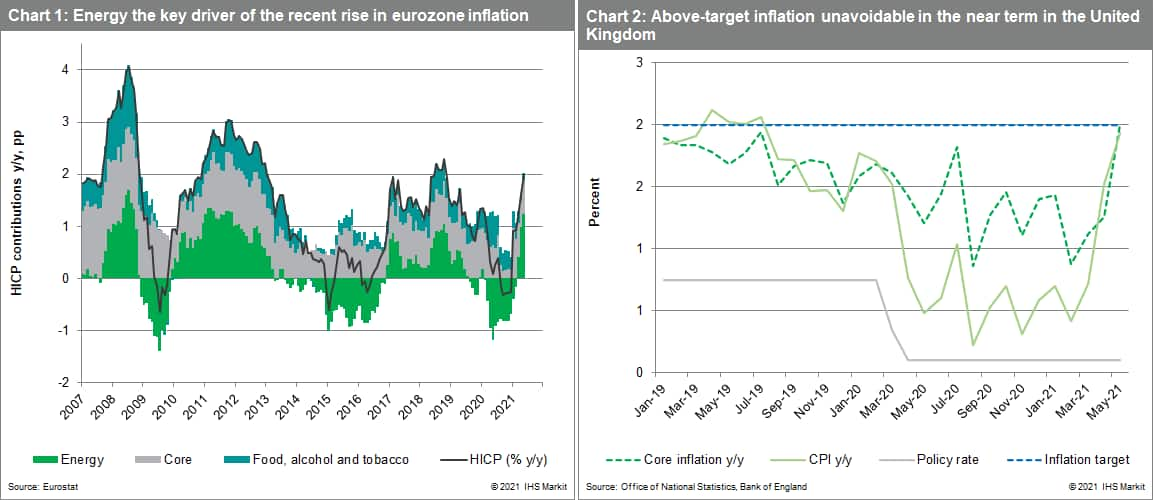

Recent rises in Western European inflation have largely been driven by energy prices (Chart 1), while output gaps remain large and demand-side inflation pressures modest. IHS Markit does not expect policy rate rises in the eurozone until 2025.

The ECB's current guidance stipulates that asset purchases under the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) will continue until at least March 2022 and that there will be no reduction in the stock of assets held under the PEPP until from end-2023. We expect a tightening of policy via a PEPP-driven balance-sheet reduction only from 2024, with rises in policy rates to follow from early 2025, initially in the form of a less negative deposit facility rate (DFR).

A risk to the forecast is a(n) (low probability) "early" tightening scenario, which could materialize in the case of persistently higher headline inflation rising inflation expectations and leading to lasting second-round effects. Another risk is that bond markets conclude that the ECB is doing too little, too late, in response to the changed inflation outlook, with bond yields rising more quickly as a result, tightening financial conditions.

United Kingdom: Bank of England in no rush to tighten

Minutes of June's meeting revealed that the MPC believes that the UK will experience a "temporary period" of strong GDP growth and above-target CPI inflation. These transitory pressures are not likely to influence monetary policy. While building global input cost pressures were increasingly being passed to prices, and CPI inflation is likely to exceed 3% (Chart 2), a higher peak than previously forecast, market-derived measures and surveys suggest that inflation expectations are well anchored. Consequently, we continue to forecast that policy rate hikes will begin only from late 2023.

Elsewhere in Western Europe, monetary tightening is expected to continue in Iceland, likely already in 2021, and to start in Norway in early 2022.

Central Europe and the Balkans (CEB): Czechia and Hungary leading tightening

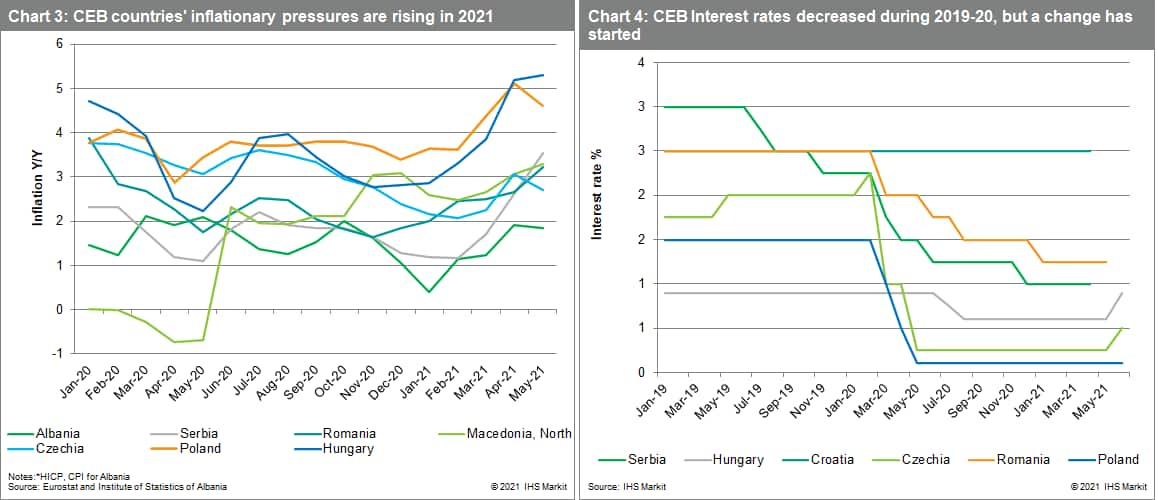

The CEB region is facing more significant inflation pressures and, accordingly, will experience more tightening (Chart 3). Hungary in late June became the first country in the EU to raise interest rates in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic (Chart 4), and further tightening is likely in the third quarter. Czechia closely followed Hungary, and the Czech National Bank (CNB) is the central bank within the region expected to introduce the most significant tightening in 2021-22.

Although the central banks of Poland and Romania have maintained a dovish stance thus far, tightening in Czechia and Hungary could force them to act sooner than previously expected, possibly by late 2021. Among the smaller economies, Albania is expected to raise rates in 2021 and 2022, and Serbia in 2022.

Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA): Leading the way and more in store

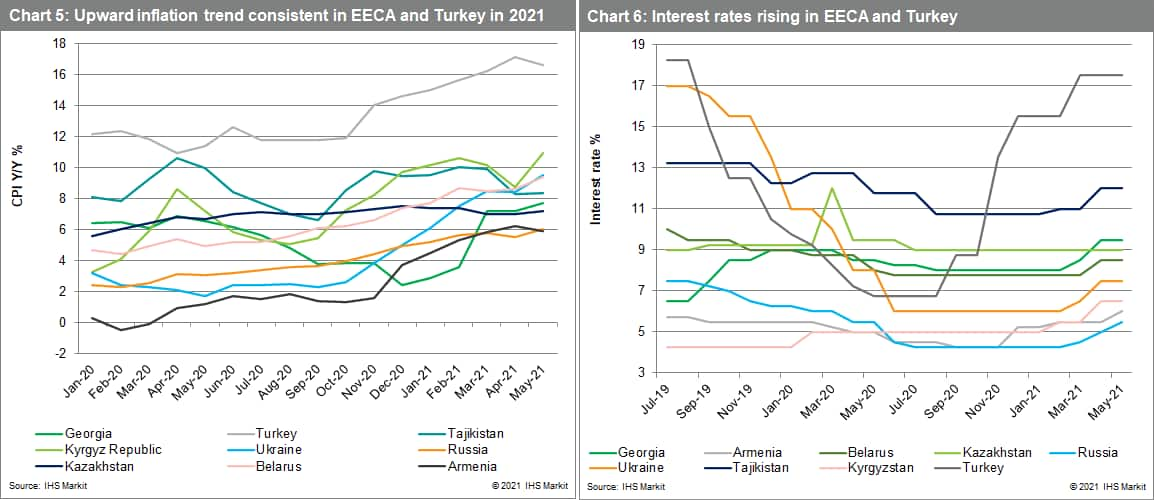

The EECA countries have experienced the most pronounced monetary policy shift globally since the start of the year. Thus far, the region's net energy importers have been tightening their policy, with Russia, as a net energy exporter, being the only exception. Severe inflationary risks, both transient and more persistent, have forced Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Ukraine to raise their policy rates, in some cases multiple times already (Charts 5, 6). Inflation is accelerating owing to rebounding market prices for energy and food, as well as exchange-rate volatility. Moreover, domestic demand has started to recover, pushing up core inflation. We expect further monetary tightening by most EECA central banks, including those of Kazakhstan and Moldova, through 2021 and early 2022.

However, given that several EECA financial systems are still developing, in some cases, higher policy rates may only reflect the monetary authorities' higher inflation expectations. These countries' central banks often react to exchange rate pressures. These may either be direct (for energy exporters) or indirect (for energy exporters' trade partners). This may also hold for central banks that are officially operating an inflation targeting framework. In the case of higher oil prices, energy exporters' appreciation pressures increase. If the monetary system is undeveloped, the central banks may try and prevent the exchange rate from appreciating in order to safeguard competitiveness, and these interventions themselves are inflationary.

Some EECA central banks also face the risk of increased political pressure, and this may derail or delay tightening, particularly if the pace of economic recovery falters. Especially in the less developed financial systems, risks to macroeconomic stability would increase as a result, ultimately leading to the need for more monetary tightening in the medium-to-long term.

Posted 30 June 2021 by Ken Wattret, Vice-President, Global Economics, S&P Global Market Intelligence and

Venla Sipilä-Rosen, Principal Economist, Europe and CIS, Sovereign Risk Service Coordinator, S&P Global Market Intelligence