Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

04 Aug, 2025

By Brian Scheid

The US unemployment rate was little changed in July, but the number of Americans out of work for a long time surged to the highest level since the COVID-19 pandemic.

Meanwhile, the number of new workers struggling to find their first job soared to levels not seen in decades. The labor market, which experienced historic employment growth, low joblessness and demand for labor that consistently outpaced the supply of workers in recent years, appears to be losing momentum as hiring slows and people have a harder time finding work.

Several factors have affected the job market, including stricter federal immigration policy, which has reduced the supply of workers, and higher tariffs and interest rates, which have stalled companies' hiring plans.

"If the labor market was a bathtub and the faucet is labor supply, that faucet has been turned off," said Sam Kuhn, an economist at Appcast. "At the same time, new employment opportunities just aren't what they were two or three years ago."

Hours after the jobs report was released, President Donald Trump announced on Truth Social that he planned to fire the commissioner of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Erika McEntarfer, for what he claimed were politically motivated revisions to jobs data. Economists and government officials have repeatedly refuted such claims.

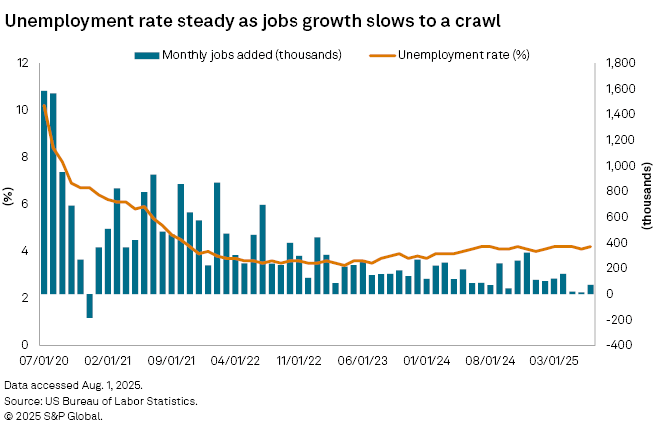

The US unemployment rate was 4.2% in July, according to an Aug. 1 report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The rate has been between 4% and 4.2% since May.

The US added 73,000 jobs in July, but job growth is slowing more than previously believed. The bureau also significantly revised its numbers for earlier in the year, lowering the May total to 19,000 from 144,000 and the June total to 14,000 from 147,000.

So far in 2025, 597,000 jobs have been added. This compares to 1.07 million jobs in the first seven months of 2024 and 1.68 million in the same period in 2023.

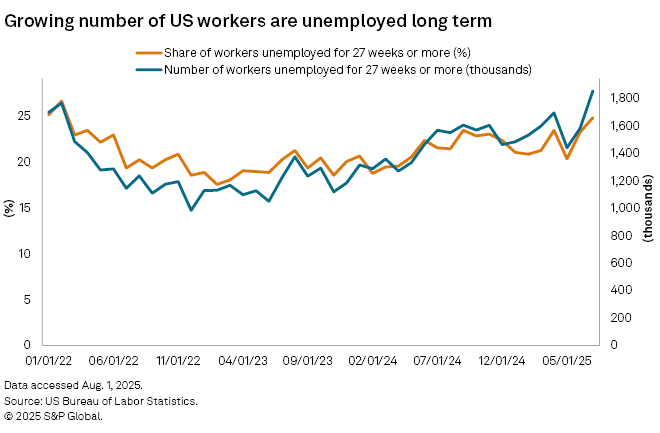

Meanwhile, the number of long-term unemployed workers — those out of a job for 27 weeks or more — jumped to 1.83 million in July, its highest point since December 2021. This group now makes up nearly 1 in 4 unemployed Americans, the largest share since February 2022.

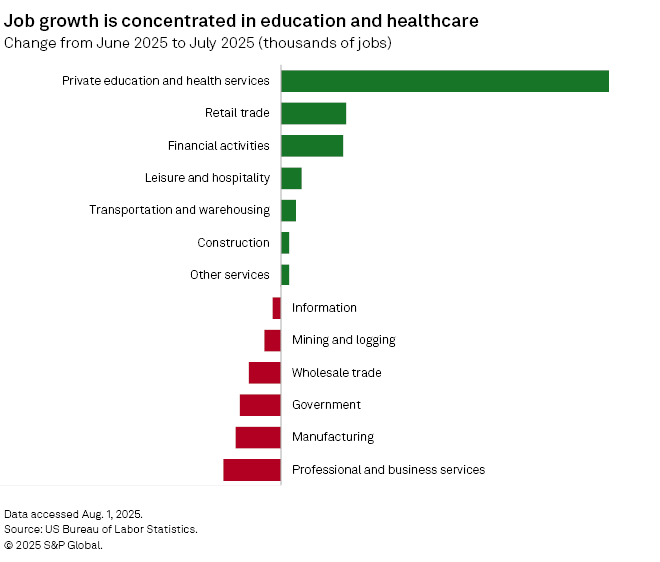

The rise in long-term joblessness is happening at the same time as a major imbalance in job growth, said Laura Dawson Ullrich, director of economic research with Indeed.

In the past year, healthcare and social assistance accounted for 48.8% of all job growth, yet this subsector only makes up 14.6% of total employment.

"So, if you are someone looking for a job in one of the slower-growing sectors, like manufacturing or professional and business services, it may be very difficult to find a job," Ullrich said. "We have been in a low-hire/low-fire environment now for quite a while, and the lack of churn in the labor market in some of these sectors is not creating much space for new workers."

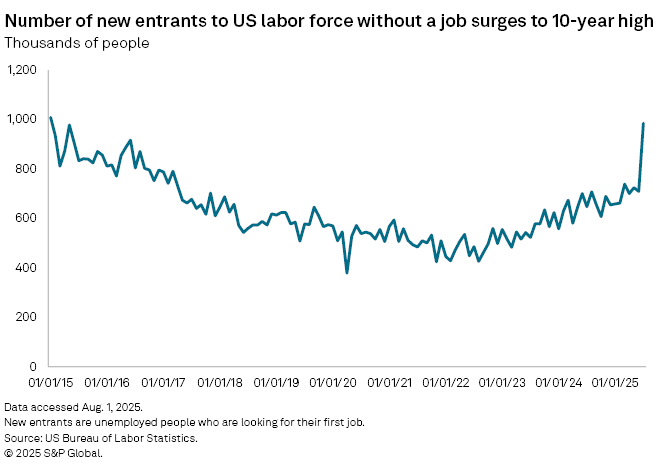

This has made it difficult for new entrants to the workforce to land their first job.

The number of new entrants to the workforce who are unemployed surged to 985,000 in July, a nearly 40% increase from June. This was the biggest monthly increase since the government began tracking it in the late 1960s.

The rise could be attributed to recent high school and college graduates who are struggling to find jobs.

"There is a distinct possibility that more 2025 grads are starting out as unemployed — and looking for jobs currently — when in the past they would have had a job waiting for them after graduation, never showing up as unemployed in the data," said Ullrich.

Households may also be facing income constraints, which could be pushing dependents to seek work and contributing to the rise in new job seekers, Ulrich noted.

Concentrated growth

Appcast's Kuhn said the rise in unemployed new entrants could be due to job growth being concentrated in healthcare and hospitality, sectors that may not require the same education level as others. Thousands of new college graduates seeking careers in tech, for instance, may be entering a field that is no longer hiring.

"The rise is illustrative of first-time job seekers, such as recent graduates, having a tough time finding a job," said Nicole Cervi, an economist with Wells Fargo. "The drivers of the climb are difficult to pin down in real time, but a few sources come to mind: Elevated uncertainty about the economic outlook may be making firms hesitant to invest in new human capital, while the broader adoption of AI may be limiting the need for entry-level positions in general."

A jump this large in one month may signal an issue with the underlying data, said Preston Mui, an economist at Employ America.

"Perhaps there's something going on with unemployed new graduates; maybe companies are delaying or just not hiring new graduates," Mui said. "But I would be cautious taking too much from these smaller cuts of the household survey. I would not be surprised to see it reverse next month."

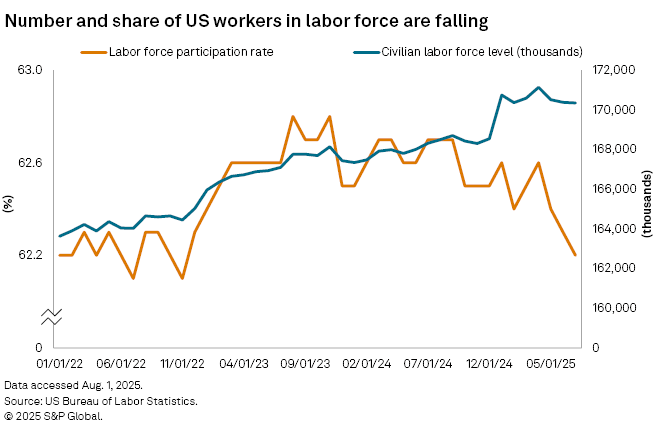

The labor force participation rate, which is the percentage of the working-age population that is either employed or actively seeking employment, fell to 62.2% in July, the lowest level since November 2021.

The civilian labor force dropped to 170.3 million in July, its lowest point since late 2024. The US labor force has now declined for three straight months, falling by 793,000 from its peak in April.

The decline in the workforce and participation rate can be attributed to an aging population and stricter immigration enforcement, according to Guy Berger, a senior fellow at the Burning Glass Institute.

"With immigration flows slowing so sharply, labor supply is expanding much more slowly or not at all," Berger said.