Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

24 Jul, 2025

| Boxcar platforms like the one pictured above are key tools for evaluating polymetallic nodule resources in the deep sea — which some consider a new frontier for mining critical battery metals Source: TMC the metals company Inc. |

The race to gain access to the critical minerals deep below the ocean surface will be defined by who sets the rules for the underwater abyss and the certainty of the regulations, according to industry participants.

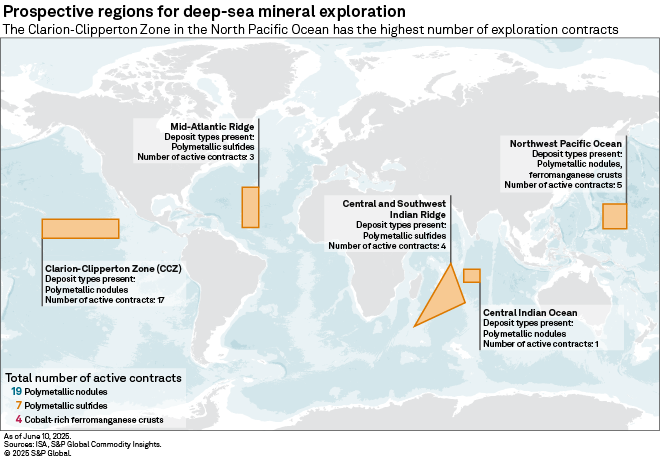

US President Donald Trump on April 24 ordered federal agencies to start granting licenses for the exploration and development of deep-sea resources within the US Exclusive Economic Zone and areas beyond national jurisdiction, including the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the central Pacific Ocean. The Clarion-Clipperton Zone is estimated to contain more cobalt and manganese than all known land deposits combined, along with large quantities of nickel and copper, according to the US Geological Survey. These metals play key roles in electric vehicles, defense technology, next-generation robotics and AI.

But mining in international waters is regulated by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which currently forbids all commercial exploitation of deep-sea resources. Established by the United Nations in 1994, the ISA has yet to develop mining regulations covering more than half of the world's oceans. At least 32 countries have either called for a precautionary pause or an outright moratorium on such activities due to concerns about environmental harm. Member states are meeting from July 21–25

Frustrated with the pace of UN-led talks, one company, TMC the metals company Inc., applied for a commercial recovery permit from the US government in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, bypassing the UN institution altogether. And more might be coming.

"The thing that's been holding the big players from getting involved in deep-sea mining is regulatory uncertainty," Gerard Barron, CEO and chair of The Metals Co., told Platts, part of S&P Global Commodity Insights. "Now that the regulatory uncertainty has disappeared, as certainly is the case in the US, I think you would expect more big players to get involved."

Lockheed Martin Corp., a US defense and aerospace giant, recently entered talks with several companies

"Ultimately, it will come down to whether these companies believe they will ever be able to extract resources through the international system via the ISA and, if so, when that will be. Companies will see the US system as an alternative that will allow them first-mover advantages and speed ahead of the competition," Diora Ziyaeva, partner and US region co-lead of mining and natural resources at Dentons LLP, told Platts.

Legal questions

While the US' recent executive order has stirred a renewed sense of excitement in the industry, some have raised questions about its legal underpinnings.

The international seabed is an area of a "common heritage of humankind" according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and no single country can pursue development of this resource unilaterally.

The United States never signed the UNCLOS and therefore is not bound by its charter. Instead, Trump's

Some have argued that US law will not protect these companies from the risk of litigation by either the ISA

"While DSHMRA allows US companies to apply for deep-sea mining licenses, the US remains a non-party to UNCLOS. As such, citizens issued licenses or permits by [the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] would have no legal recourse to protect their claim to explore and/or recover seabed minerals in [the areas beyond national jurisdiction]," the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition,

Additionally, the ISA can revoke licenses issued under the international system to companies seeking US licenses.

"ISA can take legal action against license holders who violate the Law of the Sea Convention. They are currently exploring the possibility of revoking licenses," Ziyaeva said.

Market risk

Uncertainty around legal regimes in international waters could mean market risk for companies seeking US licenses.

"The primary risk for such companies is international pushback against their supply chains and markets," said Alex Gilbert, director of space and planetary regulation at Zeno Power, which develops advanced batteries for undersea work.

"It is feasible that countries may pass domestic laws restricting their companies from doing business with such US-authorized companies, as well as import bans for metals or products using such resources," Gilbert told Platts.

The Metals Co.'s Barron said he is not concerned about the supply chain risk.

"The US is such an important trade partner for the world. I don't see that a suggestion that some countries would ban trade with the US-licensed metals could hold any water, at all," Barron told Platts. "The real risk is China dominating the critical mineral markets today. The countries would soon realize that having an alternative supply of these critical minerals from the deep sea will be very important."

No mining code

The ISA says it understands the urgency to develop deep-sea resources and the sense of frustration from the mining industry.

"I acknowledge there is a race to gain access to minerals that is driving some of the urgency we see today," Leticia Carvalho, secretary-general of the ISA, wrote in a June 10 opinion piece for The Economist. Carvalho said that the ISA will strive to finalize the mining code in 2025.

No industry expert reached by Platts expects the mining code to be finalized this year.

"There are still significant issues that remain unresolved. More saliently, the bloc of countries calling for an environmental moratorium is crystallizing against allowing ISA to complete the mining code," Gilbert said. "It may prevent the establishment of a mining code indefinitely, ultimately dooming the ISA system."

The ISA governs by consensus and the opposition within the organization could prove insurmountable to passing the mining code.

With every meeting concluding without a mining code, more companies will be looking at the US-based system to develop deep-sea resources as an alternative.

"Companies will see the US system as an alternative that will allow them to gain first-mover advantages and speed ahead of the competition," Ziyaeva said.

The ultimate trigger for the industry to switch to the US-based system might not come from the ISA but from The Metals Co.

"If the ISA fails to agree on a mining code for the area by the time The Metals Company successfully receives a commercial recovery permit, multiple companies will strongly consider moving to the US system," Gilbert said.

Barron told Platts on July 1 that The Metals Co.'s US ocean mining permit is coming "sooner than people expect."