Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

23 Jun, 2025

By Brian Scheid

The slowdown in the US job market may be a challenge for unemployed workers, but it could prove to be a boon for the larger domestic economy.

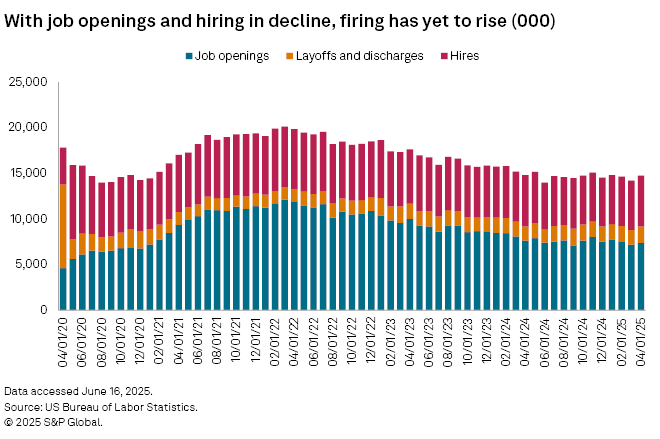

Companies have slowed hiring near levels last seen over a decade ago, the number of job openings has plummeted from 2022 highs and wage growth has stalled. Still, a wave of layoffs has yet to materialize and the unemployment rate has remained steady for more than a year.

Dubbed the "no hire, no fire" market, the labor picture in the US has essentially slowed to a crawl, but economists believe it may not ultimately prove to be an economic drag.

"It is a difficult state of play for workers looking for a new job, but it is supportive of lower inflation, higher productivity and persistent economic growth in the long run," said Thomas Simons, chief US economist at Jefferies, in an interview.

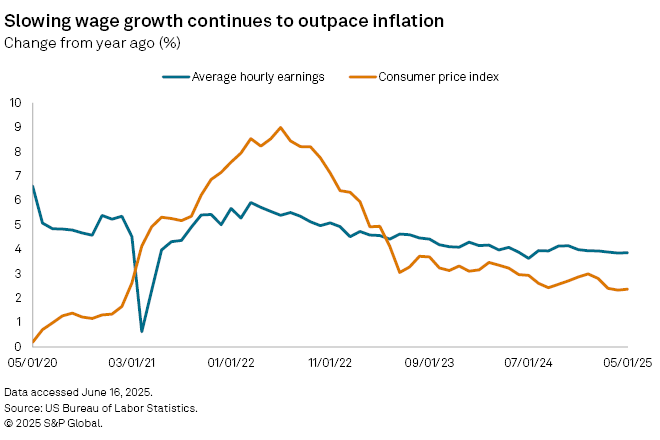

Annual wage growth, for example, has been at 3.9% every month since December 2024, still outpacing inflation. But as it grows more difficult for workers to move to another job amid slowing hiring, higher salaries will prove more difficult to find. Slowing wage growth could help slow inflation, ultimately pulling it closer to the Federal Reserve's 2% goal.

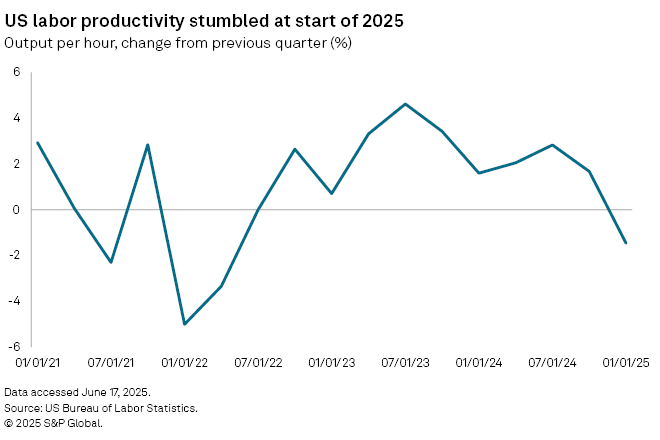

In addition, without new employment to lure them away, workers will stay in their current positions longer, potentially boosting productivity, according to Simons.

"Fewer people quitting their jobs means that firms are spending less on recruiting and retention, and workers who stay in their jobs have slower wage growth than those who capture a one-time step up in switching jobs," Simons said. "As people stay in their roles longer, they gain more experience and teams begin to synergize, so output improves."

Simons has dubbed the current market "The Great Stay." The term references "The Great Resignation," when the rate of employees who voluntarily left their jobs surged to 3% in November 2021, up 80 basis points from a year earlier, as companies worked to meet post-pandemic demand by ramping up staffing.

The current no hire, no fire environment could be partly linked to concerns about sourcing labor, particularly as the Trump administration ramps up immigration enforcement, James Knightley, chief international economist with ING, said in an interview. Sectors with historically high migrant workforces, such as food and agriculture, construction, and leisure and hospitality, may need to boost pay to attract more Americans to this work, according to Knightley.

"This may mean that we see relatively modest payrolls growth. But because the labor supply is constrained, we don't see the unemployment rate increase meaningfully," Knightley said. "Therefore, we could see weak payrolls growth, but rising wages with limited movement in unemployment."

Still, an overall cooling jobs market makes the economy more vulnerable to external shocks.

"A certain level of dynamism keeps people interested and motivated to work hard," Knightley said. "But if there is a sense that there is no reward to working hard as you will stay in the same position whatever happens, I would be worried about a staleness creeping into the wider economy that may be negative for economic activity over the longer term."

Ultimately, the jobs market will need to come into better balance, with demand for labor matching closer to labor supply in order to propel economic growth further. For now, however, the no hire, no fire market will improve productivity while limiting the rise in inflation, according to Simons.

"I think it's a necessary step in the process towards normalizing from the crazy days of the pandemic," Simons said.