Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

30 May, 2025

By Tom Jacobs and Noor Ul Ain Adeel

|

Damaged structures are seen in Chimney Rock, North Carolina, on Oct. 2 after the passage of Hurricane Helene. North Carolina incurred an estimated $53.6 billion in damages from the storm, which caused 96 deaths, destroyed thousands of homes and washed away miles of roads. |

The possibility of another active hurricane season and concerns over emergency management at the federal level have raised questions about how US states will fund and manage disaster recovery.

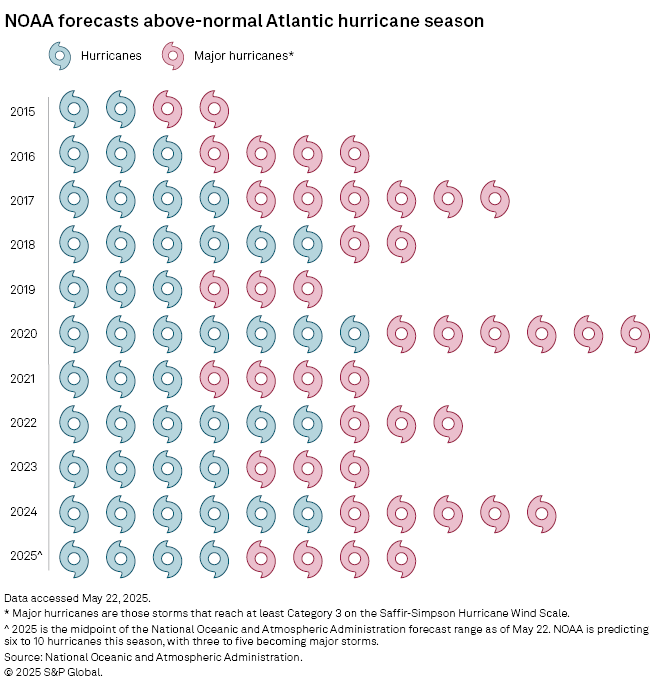

Researchers including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates that there will be an "above-normal" number of named storms for the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season, which runs from June 1 through Nov. 30.

NOAA is forecasting 13 to 19 total named storms for the season, with six to 10 expected to become hurricanes, defined by winds of 74 mph or higher. Three to five are expected to evolve into major hurricanes, or Category 3/4/5, with winds of 111 mph or higher.

With the Trump administration continuing to shrink federal disaster spending and shift more of that burden to state emergency managers by downsizing the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), alarms are being raised over states' ability to handle disaster relief should a major storm strike.

Keefe Bruyette and Woods analyst Meyer Shields said that if more responsibility for disaster response is shifted to the states, it's a good bet the transition will be rough.

"There's less bureaucracy when things are administered on a state level, but that doesn't mean that all states are capable and it doesn't mean that the transition will be handled well," Shields said in an interview. "Transitions are always tough and things get lost in the shuffle. That's just a reality."

FEMA's footprint may shrink

The Trump administration has not issued a final decision on how disaster relief standards will change as it looks to shrink the disaster relief agency's footprint and cut federal costs for disasters. A number of objectives were detailed in a memo obtained by CNN that was sent to an official with the White House Office of Management and Budget by then-acting FEMA director Cameron Hamilton.

Hamilton proposed tightening requirements for states to get assistance after a disaster, reducing the federal government's share of recovery costs and limiting the facilities eligible for assistance. The proposal also recommends restricting the types of facilities eligible for assistance and denying all major disaster declarations for snowstorms.

"The primary purpose of this memorandum is to identify short-term actions to rebalance FEMA's role in disasters before the start of the 2025 hurricane season," Hamilton wrote in the memo.

At this point, there's no clear indication that FEMA or the White House are following the recommendations outlined by Hamilton, who was fired May 8 after telling lawmakers that he did not support dismantling FEMA. Hamilton was replaced by David Richardson, assistant secretary for countering weapons of mass destruction at the Department of Homeland Security.

"FEMA is shifting from bloated, DC-centric dead weight to a lean, deployable disaster force that empowers state actors to provide relief for their citizens," a DHS spokesperson said in an email to S&P Global Market Intelligence. "The old processes are being replaced because they failed Americans in real emergencies for decades."

Ashley Beetz, a spokesperson for Louisiana's Governor's Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness, said in an email that the state "works closely with FEMA and other partners to ensure alignment and coordination," and that any updates or guidance provided by FEMA "will be reviewed and integrated into our preparedness efforts as appropriate."

The emergency management agencies for Florida, North Carolina and Georgia did not respond to a request for comment.

Fed changes amplify risk

Insurers have been hesitant to comment on how the upheaval at FEMA and other policy shifts related to climate risk might affect their industry. The American Property Casualty Insurance Association did not provide a comment when approached.

Along with the proposed FEMA changes, the Trump administration has also overseen layoffs at NOAA and the decommissioning of its billion-dollar event database, as well as layoffs and early retirements at the National Weather Service. Such changes could potentially turn a natural catastrophe that becomes an insurance event into a "broader-based economic event," CFRA Research analyst Cathy Seifert said.

"The combination of what's being done to NOAA and what's being done to FEMA, you run the risk of a natural catastrophe being amplified into an economic event and potentially an awful personal tragedy," Seifert said in an interview.

FEMA's effort to shift more responsibility to states puts homeowners insurance markets in particular at risk, Seifert said. If states are given more to handle, insurers will look closely at which states are prepared for a natural disaster and have "the willingness and the leadership to pick up the slack versus those who are going to stick their head in the sand and pretend that climate change is a hoax," Seifert added.

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners wrote a May 2 letter to Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick and other members of Congress that emphasized the importance of "maintaining uninterrupted public access to traditionally published NOAA data."

The NAIC said it wrote its letter after there was a "disruption in public access to NOAA data" and multiple state insurance departments fielded concerns from insurers and catastrophe modeling firms that said the data is crucial to their operations.

2025 looking like 2024

The late-season activity in 2024, which included two major hurricanes within a two-week span, is likely to happen again in 2025. Sea surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico and Western Caribbean are warmer than last year, and current trends suggest a return to La Niña later in the season, said AccuWeather meteorologist Paul Pastelok.

Along with NOAA, AccuWeather is also expecting an above-average season, as does Colorado State University's Department of Atmospheric Science. Colorado State predicts a 26% chance of a major hurricane making landfall on the US East Coast and a 33% chance of one striking the Gulf Coast.

The current flow of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, which involves water temperature changes in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, is similar to last year and mirrors other active hurricane seasons, according to Pastelok. In 2012, for example, there were 10 hurricanes, two of which were major, while the 2017 season had 10 hurricanes, six of them major.

The 2024 season got off to an ominous start when Hurricane Beryl reached the Texas Gulf Coast on July 8 as the earliest Category 5 ever in the Atlantic basin. Things went quiet after that until Hurricane Debby hit Florida's Big Bend coast on Aug. 8 as a Category 1 event.

This continued with the arrival of Hurricane Helene on Sept. 26, also on the Big Bend coast, as a Category 4 storm. While Florida was spared the worst, such was not the case in the following days.

Helene went through Georgia and South Carolina before reaching western North Carolina with severe flooding and wind damage. Insured losses from Helene were estimated to be between $8 billion and $14 billion in insured losses.

Hurricane Milton, the final major storm of the season, reached Category 5 strength as it set a path toward Tampa Bay, Florida. The storm lost some of its intensity before making landfall at Siesta Key, Florida, on Oct. 9, well south of the Tampa area, but still resulted in between $22 billion and $36 billion in insured losses in its trek across the state.