Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

16 Apr, 2025

| Kunekune pigs and solar panels at the Mammoth North Solar Project in Indiana. |

Solar energy developers are increasingly looking to open their facilities to another type of farming: crops and livestock.

Agrivoltaics, the dual use of land for solar energy generation and agricultural production, is getting more attention, according to a July 2024 report released by the Solar and Storage Industries Institute. More than 70% of farmers are open to large-scale solar projects on their properties if system designs allow for continued agricultural production, according to the report.

About 10 GW of US solar, or 7.7% of the fleet, is agrivoltaics, according to US National Renewable Energy Laboratory's InSPIRE data on the Open Energy Information platform.

"Instead of viewing solar development and farming as competing land uses, agrivoltaics basically will integrate them to create synergies between both," Ed Baptista, vice president of development and agrivoltaics at private developer Doral Renewables LLC, told Platts, part of S&P Global Commodity Insights.

Solar is often developed on land that could also be used for farming, creating tension between the agricultural and energy commodities. The American Farmland Trust estimated that 83% of new solar development could occur on agricultural land.

However, solar facilities can be modified to enable agrivoltaics, increasing the overall yield from the site.

For example, at Doral Renewables' 400-MW Mammoth North Solar Project in Starke County, Indiana, the site's vegetation management is done by sheep grazing.

"In that project, we have 1,000 sheep already in the area, doing some sheep grazing, and the plan is to increase that amount maybe up to 4,000 in two or three years," Baptista said, adding that the site, in the northwestern part of the state, is also being used for hay production.

| Donkeys, alpacas, sheep and a dog out on a sunny day at the Mammoth North Solar Project. |

| Source: Doral Renewables LLC. |

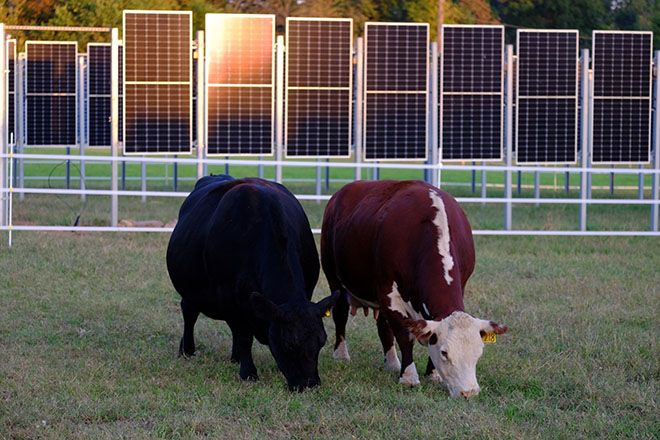

Besides sheep, animals such as Kunekune pigs — which do not root or damage the solar installation — and chickens can be part of agrivoltaics. Cattle can also be used, but there are some challenges.

"The bottom line is that to be successful, the combination of the two has to be more productive than doing the two separately. If it's not more productive, then it just doesn't make sense," Dave Specca, assistant director of the Rutgers EcoComplex Clean Energy Innovation Center at Rutgers University and Rutgers Agrivoltaics Program Lead, told Platts.

Cattle still on the frontier

Cattle is the next frontier, according to Lucy Bullock-Sieger, vice president of strategy at Lightstar Renewables LLC, a Boston-based community solar developer, and chair of the Solar and Farming Association, an agrivoltaics advocacy group.

"Everybody wants to crack that code, including the federal government, because a lot of public lands are grazed by ranchers," Bullock-Sieger said, explaining that solar can help reduce the number of animals dying from heat stress because of the shade from solar panels.

Bullock-Sieger explained that rotational grazing for cattle means that solar panels need to be raised from the normal 1-3 feet above ground to 6-8 feet to prevent cattle from interacting with the panels. The panels also tabletop, meaning they are flat at solar noon in the area where the cattle are grazing.

"So, they'll graze this area for seven days, so it will be tabletop for seven days," Bullock-Sieger said. "But the rest of the array is tracking this and absorbing electrons the same way it would anyway."

| Cows grazing by vertical bifacial solar panel arrays at the Rutgers Agrivoltaics Program's Cook campus site. |

| Source: Rutgers University, Rutgers Agrivoltaics Program, Rutgers EcoComplex. |

Solar can also be incorporated with crops such as wheat, soy and hay.

"All the major grain crops we know work really well just as long as you have wide enough row spacing," Bullock-Sieger said.

Developers can also set up habitats for native pollinators like bees on site, which requires minimal use of the land, although this is technically considered ecovoltaics.

Advocates of agrivoltaics said a solar site's agriculture needs have to be considered during initial development.

Solar farms developed as agrivoltaics need to have row space to accommodate farming equipment, for example. Additionally, there can be different fencing needs depending on the animals grazing. The soil may require additional care.

Single-axis tracker panels typically make the most sense for agrivoltaics because of their flexibility. For single-axis trackers, anti-tracking can be used for times when crops need a lot of light.

"After you cut the hay, it needs to dry very quickly," Specca said. "So, for a couple of days, you would have the panels do anti-tracking, so the sun is getting down to the hay crop that's been cut and it's drying it out quickly like it normally would in an open field."

Community as important as capital

Solar developers benefit from agrivoltaics because it helps with community acceptance while farmers benefit because it provides a steady, sustainable source of income. There are also some environmental and sustainability benefits such as soil health and preservation, moisture retention and livestock that benefit from shade and grazing.

"It would just be a shame to lose all that farmland just in order to produce the clean electricity we need. We almost need to come up with a solution that still allows for both," Specca said.

One challenge is that developers generally want to optimize solar energy production, but the addition of agrivoltaics can increase capital costs, which can therefore increase the cost of energy.

"Without the [investment tax credit (ITC)] base compensation right now, we could not do agrivoltaics," Bullock-Sieger said.

Agrivoltaics might require developers to navigate different permitting needs.

| Dried down soybeans prior to harvest that were grown at the Rutgers Agricultural Research and Extension Center. |

| Source: Rutgers University, Rutgers Agrivoltaics Program, Rutgers EcoComplex. |

Baptista believes agrivoltaics will proliferate within the next decade in the US.

"The industry is becoming more aware of the benefits of agrivoltaics, and we believe that's going to be the future at some point," Baptista said.

Agrivoltaics can be utilized across the US, adapting to different local environments and needs.

"You'll see it first where the benefits are the greatest, like … in the Northeast, where there is a lot of development pressure and land values are high," Specca said. "You'll also see it in the Southwest, where there's a lot of excess sunlight … so that extra shade that the panels produce really benefits the crops there and reduces their water demand."