Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

15 Apr, 2025

By Karin Rives

| Workers with Plants & Goodwin cap an orphaned well in Pennsylvania with the help of a grant from the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law. |

They are found in people's backyards, by chemical plants, beneath rivers and along busy roads in the US: Millions of abandoned oil and natural gas wells that no longer have an owner.

These "orphaned" wells were never properly plugged and now leak methane into the air and groundwater, posing health risks to people living or working nearby. Many of the companies that once operated the wells have gone out of business, leaving no party legally responsible for cleaning up the sites.

But where property owners and states see a multibillion-dollar liability, Talal Debs of Zefiro Methane Corp. and other companies in a growing industry are finding opportunity.

A former JPMorgan Chase & Co. executive director turned environmental services entrepreneur, Debs is tapping into the $4.7 billion orphaned wells program created by the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law, at least for now — and business is booming.

The companies remove old equipment from the well and wellhead and add cement plugs at different depths of the well. The well is then permanently sealed with a wellhead cap to keep emissions from migrating.

Jake Hollabaugh, business developer for the oilfield services company CSR Services, said there are at least 10 companies for every bid to cap orphaned wells in Ohio, where CSR does most of its work. While abandoned wells with no owner have always been part of the mix, that side of CSR's business picked up as the federal program took off the past couple of years, he said.

"There are hundreds of thousands of open wells just in Ohio and Pennsylvania," Hollabaugh said in an interview. "We'll be plugging wells for the next probably 100 years."

After a monthlong hiatus earlier this year, some federal grants for the orphaned well program are again reaching states that, in turn, contract with well-plugging firms. Companies in the well-plugging business and environmental advocates are watching the US Interior Department to see what will happen with the next rounds of grants under the 2021 federal law.

As of September 2024, about $1.3 billion of the $4.7 billion appropriated for the federal program had been committed, according to the program's annual report. Grant applications from 13 states under the second phase of the program, known as the Formula grants, are under review, agency spokesperson Elizabeth Peace said in an email.

Meanwhile, draft guidance for the third and final round of funding, known as Performance grants, has been removed from the Interior Department's website.

"In accordance with the Unleashing American Energy executive and secretarial orders, the regulatory improvement grant guidance is undergoing policy review," Peace said. "Once guidance is revised, states will have an opportunity to apply for additional orphaned wells program grants."

Carbon market to the rescue

Zefiro is one of several companies that are turning to the rejuvenated voluntary carbon market to secure a reliable revenue stream and grow their business. Debs, the CEO of Zefiro, said it is the only US company focused solely on capping orphaned wells.

Companies with emission reduction goals can buy credits on the carbon market to help meet their climate goals.

Zefiro has projects across oil and natural gas fields in Appalachia and recently expanded into Oklahoma, where three well projects have been listed on the American Carbon Registry (ACR). The ACR program verifies and validates carbon credits used for environmental projects worldwide.

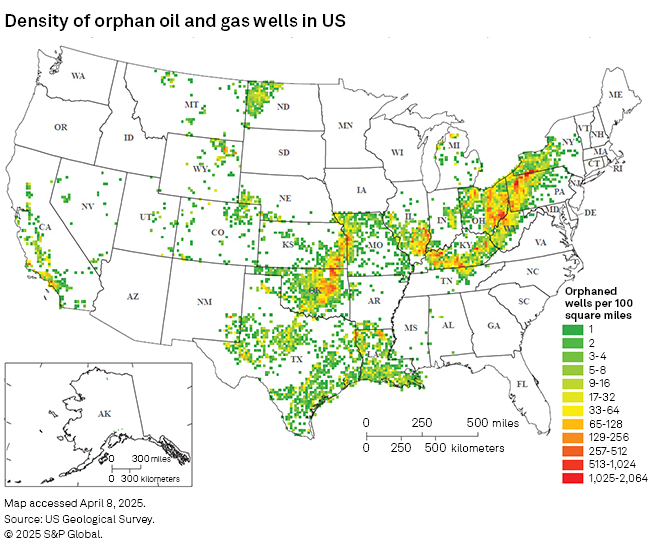

Debs hopes the voluntary carbon market will be the mechanism that eventually monetizes cleanup of an estimated 4 million wells in 26 states — along with many millions more abandoned wells to which operators still hold title.

"We think it can provide a very deep market for the carbon market — a very fungible, highly additional product — and really be solving a tangible problem for us here in the developed world," Debs said in an interview.

The company expects to issue its first carbon credits this spring.

"It will be the first time that we're getting cash coming through the carbon markets to pay for the plugging of orphaned wells," Debs said. "We can't think of a stakeholder who doesn't benefit from that."

The "additional" value of carbon credits is linked to the actual reduction of methane emissions they represent. At the time the bipartisan infrastructure law took effect, the US Environmental Protection Agency estimated the country had about 3.5 million abandoned wells, emitting roughly 7.1 million metric tons of CO2e annually.

To help tackle this problem, the ACR in 2023 published the world's first methodology for leveraging carbon markets and high-quality offsets to help plug wells in the US and Canada, a spokesman for the registry said in an email.

Costly projects, but states made progress

Plugging an orphaned well can cost anywhere from tens of thousands of dollars to about $2 million.

Zefiro's corporate clients include datacenter and warehouse developers who need to remediate properties before they can build and can afford the work.

For a private landowner, paying for the cleanup may be harder, said Luke Plants, CEO of Plants & Goodwin, a third-generation Pennsylvania oil and gas field services company. Zefiro acquired the company in 2023 to be able to expand nationwide.

"You're at the mercy of whatever the state's funding is for those kinds of remediation projects, and where that well ranks on the priority matrix," Plants said in an interview. "So if it's not close to your house, it's not visibly leaking methane and there's no surface contamination, it could be a long time before that well gets addressed."

| A rusty, orphaned well in Erie County, New York. |

One recent project that Plants & Goodwin handled was an old well just outside an active manufacturing plant that received daily rail deliveries of hazardous chemicals. Once the remediation workers excavated concrete covering the well, they found a "venting gassy hole in the earth beneath this facility," Plants said.

Other projects have been along Route 419 in southern New York near the Pennsylvania state line, a region with some of the country's oldest oilfields.

"They just paved over the oil wells that were there," Plants said. "For my entire life that I remember, there has always been an oil sheen that just runs down the ditch of the road whenever you get a heavy rainfall."

Nobody knows for certain how many orphaned wells exist, and estimates vary, said Ted Boettner, a senior researcher with the Ohio River Valley Institute, who has spent years documenting such wells in West Virginia. Yet, the increased focus on the problem in recent years means many more are found, he said.

"I think states have made tremendous progress," Boettner said. "They're locating and plugging orphaned wells. This is also leading us to more knowledge and a richer understanding of how hazardous they are — and it's very bipartisan, industry is onboard."