Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

10 Mar, 2025

By Brian Scheid

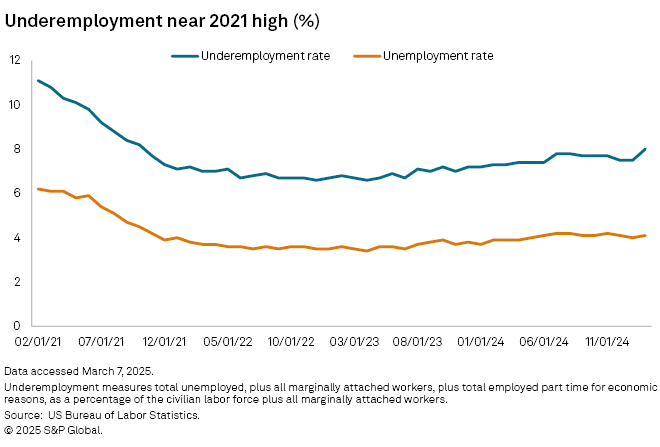

While US unemployment remains near historic lows and has moved little over the past year, a more complete measure of joblessness surged in February, rising to levels last seen in 2021 as millions more Americans struggle to find full-time work and labor demand continues to weaken.

The underemployment rate — also known as the U-6 unemployment rate and referred to by some economists as the "real" unemployment rate — jumped 50 basis points in February from January, reaching 8.0%, its highest level since October 2021, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics reported March 7.

The U-6 measure of joblessness gauges the unemployed and underemployed, those out-of-work Americans who have grown discouraged and given up their job hunts, and those marginally attached who have left the workforce but may soon return.

The jump in underemployment is taking place as consumer sentiment weakens and recession fears resurface, driven by concerns about the Trump administration's tariffs and federal workforce cuts as well as by expectations that the US Federal Reserve will hold interest rates at current levels for months.

Unemployment was at 4.1% in February, and it has not fallen below 3.9% or risen above 4.2% over the past year. Over the first two months of 2025, 276,000 jobs have been added to the US labor force, while nearly 2.17 million jobs have been added since February 2024.

However, the sudden rise in underemployment has sparked concern that one of the pillars of the US economy is weakening.

"I do think it is a warning sign that labor markets are softening and look noticeably weaker than they did last year or in 2023," said George Pearkes, a macro strategist at Bespoke Investment Group.

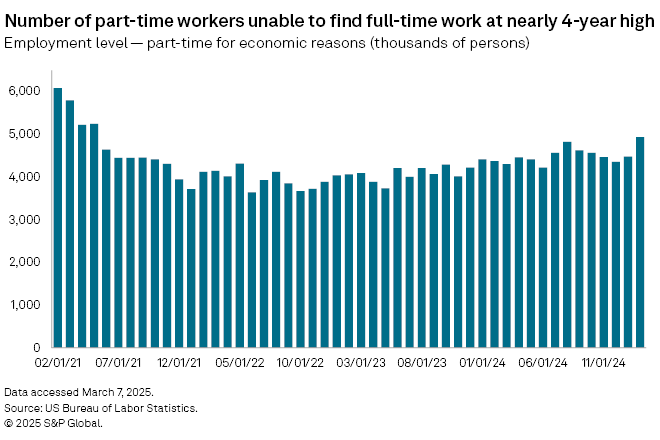

The leap in the underemployment rate appears to be tied to an increase in the number of workers who are involuntarily working part-time jobs, said Nicole Cervi, an economist with Wells Fargo.

There were nearly 4.94 million US workers working part-time jobs in February because they were unable to find full-time work, up 13% from a year earlier, the latest government data shows.

"This series has been trending up since late 2023 and illustrates some growing slack in the labor market," said Cervi. "As overall job growth has slowed down, new entrants and re-entrants to the labor market are struggling to find work and may be taking on part-time work due to the lack of full-time opportunities."

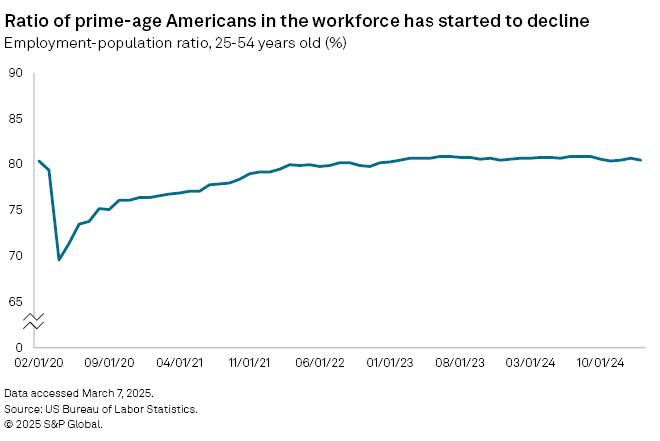

The rise in the U-6 rate reflects a jobs market with productive labor on the sidelines, and if it continues to rise, the US labor force participation rate — which was 62.4% in February, its lowest level since January 2023 — could further weaken as discouraged workers drop out of the labor market entirely, according to Cervi.

The rise in involuntary part-time workers could be a reaction to uncertainty about continued government funding, as billionaire Elon Musk's Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) attempts to slash spending and workforce levels, said Thomas Simons, chief US economist at Jefferies.

"People may be on temporary layoff, having worked for some part of the pay period," Simons said. "Time will tell as more clarity on the timing of any DOGE cuts emerges and as Congress sorts out the budget reconciliation process. It looks to me like a temporary halt on some things due to policy uncertainty."

The rise in underemployment could align with weakness in the quality of the jobs being added in the US, said James Knightley, chief international economist with ING. Only 13% of jobs created since the start of 2023 are in sectors typically viewed as "growth drivers" of the domestic economy, while the other 87% created have been in leisure and hospitality, private health and education services, and government, and are typically lower paid, less secure and more part time, Knightley said.

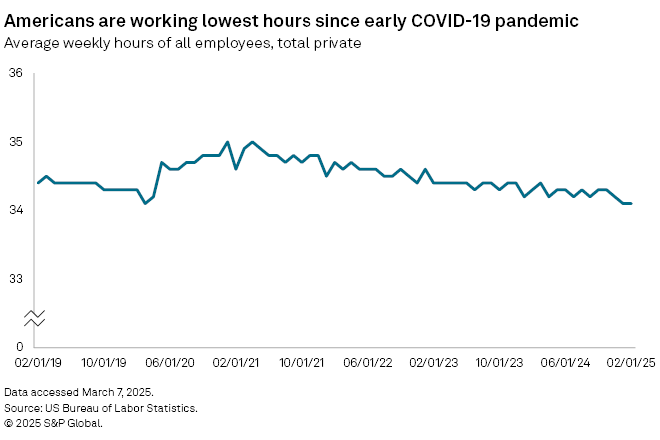

US workers worked an average of 34.1 hours per week in February, matching the low seen early in the pandemic in 2020.

This signals "some weakening of labor demand from employers," said Aaron Sojourner, a labor economist and senior researcher at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.