Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

03 Oct, 2025

|

A turbine being towed to Ocean Winds' Éoliennes Flottantes du Golfe du Lion project in France's Mediterranean Sea, one of only a few floating wind farms being built globally. |

In early September, the third and final turbine was installed at one of the first floating offshore wind farms in the world in the Mediterranean Sea.

The milestone for the 30-MW Éoliennes Flottantes du Golfe du Lion (EFGL) pilot project offshore France, developed by Ocean Winds and Banque des Territoires, marks another step in the floating wind industry's ongoing quest toward commercial-scale development.

It also underscores the slow pace of progress in the sector. When EFGL enters operation later this year, nine years will have passed since the project was first granted support by the French government.

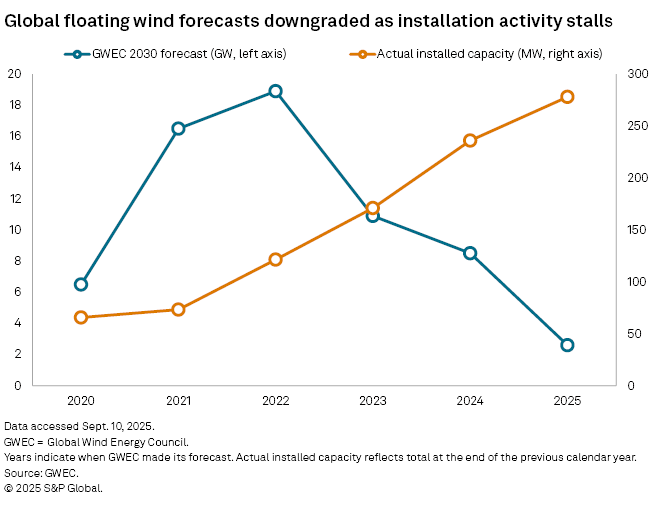

Global floating wind capacity stood at 278 MW at the end of 2024, equivalent to just 0.3% of total offshore wind installations, according to the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC), the international trade association for the wind industry.

Macroeconomic challenges that have hit traditional fixed-bottom offshore wind in recent times have been felt even more acutely by the floating wind industry, where costs are already higher.

"Floating is still in a very early stage," said Marc Hirt, country manager for France at Ocean Winds, whose shareholders are European clean energy giants Engie SA and EDP Renováveis SA. "The cost in terms of euros per megawatt is still higher than bottom-fixed and will probably remain so."

GWEC now sees just 2.6 GW of floating wind in operation globally by 2030, a stark downgrade from the 18.9 GW the organization forecast three years ago.

Andrei Utkin, associate director in the renewables markets team at S&P Global Commodity Insights, said floating wind holds promise in regions such as the UK and Japan, where deeper waters favor its deployment, but the technology's global impact will remain "very limited, at least until the next decade."

"Developers and governments are increasingly turning to more competitive energy solutions," Utkin said in an email, pointing to mature renewable technologies such as solar, onshore wind and fixed-bottom offshore wind.

Commercialization challenges

The consequence of floating wind's slow development is delayed commercialization. Annual installation volumes of 1 GW globally are now not expected to be achieved until at least 2030, according to GWEC.

"There's quite a big frustration on the side of the industry right now," said Aaron Smith, chief commercial officer at floating wind technology provider Principle Power Inc., whose WindFloat platforms are being utilized on EFGL in France.

Smith said many governments have announced big targets for floating wind but have not backed up those ambitions with the necessary investments in supply chains and port infrastructure. Meanwhile, more needs to be done in areas such as permitting, auctions and grids to support floating wind and avoid further delays in deployment.

"I think one of the key issues has been the lack of stability in terms of the framework for supporting the industry," Ocean Winds' Hirt said in an interview.

The executive specifically referenced the US, where the Trump administration has taken aim at offshore wind in recent months, ordering major projects to halt construction and placing uncertainty on the future of multiple gigawatts of capacity in the pipeline.

In Europe, floating wind auctions have had mixed fortunes in recent times.

An early-stage seabed lease auction in the UK's Celtic Sea this year saw Equinor ASA and Electricité de France SA awarded 1.5-GW floating wind sites, but a third plot of the same size went unclaimed.

Meanwhile, Norway's Utsira Nord tender — which in September received bids from two consortia led by Equinor and EDF — has experienced delays due to state aid concerns.

Supply chain companies need "at least seven to 10 years" of pipeline visibility in order to make their business cases work, according to Smith. The lack of a clear road map is leading to under-capacity in the supply chain, which pushes prices up, the executive said.

"And then when prices are higher, it's more difficult to invest in the sector," Smith said. "So it's a bit of a vicious cycle."

The European wind industry is calling for greater use of nonprice criteria to help enable supply chain investments. Tenders that prioritize price are resulting in "fragile" business cases and risk developers walking away from projects later down the line, Smith said.

"There is this risk that if you get these auctions wrong, and the government is too aggressive about what they expect from the industry in the first projects, that you have high-profile failures and you set the industry back by several years," Smith said.

Gears turning in France

In France, the country is going through a period of political turmoil just as the government plans to launch a "mega tender," known as AO10, which includes more than 5 GW of floating wind sites as well as 4 GW of fixed-bottom projects.

"It's progressing well, but we hope that the political uncertainty will not affect both the planning and the content of this tender," Hirt said.

Commissioning of the AO10 projects is expected by 2035, with France aiming to have 18 GW of offshore wind installed by then.

"What is important for floating is that there are sufficient volumes overall in order to generate the investment required in the supply chain," Hirt said about the country's offshore wind strategy.

France's first commercial-scale floating wind projects were awarded in 2024 as part of the AO5 and AO6 tenders. Ocean Winds won the 250-MW Éoliennes Flottantes d'Occitanie site, while EDF and a joint venture of BayWa r.e. AG and Elicio NV claimed projects of similar sizes.

Another tender still to be awarded — known as AO9 — includes up to 550-MW extensions to all three sites.

"France has defined a long-term ambition," Smith said. "Now that the gears are turning, it seems like we're starting to find a degree of pipeline and stability that should be able to motivate [supply chain] investments."