Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY — Dec 16, 2022

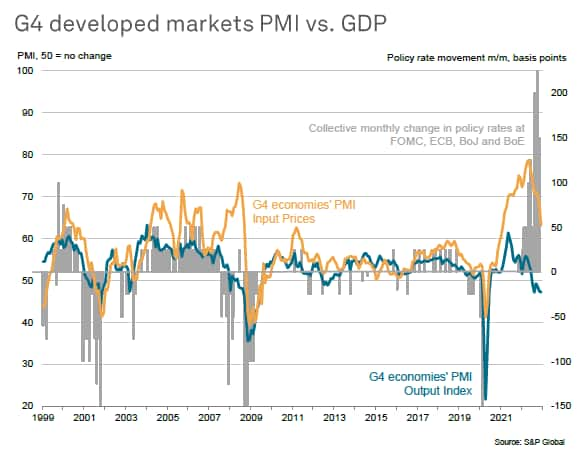

Flash PMI survey data for December showed the pace of economic growth weakening across the developed markets on average to register one of the steepest declines since the global financial crisis. Although there are some variations by country, with parts of Europe in particular showing signs of a milder recession than previously anticipated, the general trend is one of falling demand accompanied by healing supply chains. Jobs growth has cooled markedly as the need to work through an unprecedented accumulation of backlogs of work goes into reverse. As such, the environment appears to be shifting from one of strong inflationary forces this time last year to one where disinflationary forces are starting to dominate.

The flash PMI data indicated a further deterioration in the health of the global economy at the end of 2022. Collectively, the survey data covering the US, eurozone, UK and Japan pointed to output falling across the major rich-world economies for a sixth successive month in December. The rate of decline accelerated to the highest since August and, excluding the initial pandemic lockdowns, was the steepest since the series inception in October 2009.

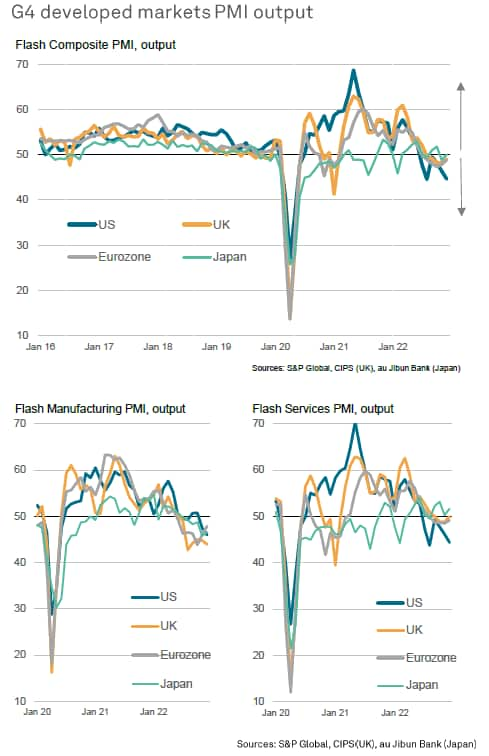

There were mixed trends within the four major economies, however, with an accelerating downturn in the US contrasting with moderating rates of decline in the eurozone and the UK. Business activity meanwhile stabilised in Japan after having slipped into decline in November.

Comparisons with official statistics suggest that the PMI data are consistent with US economy contracting at a quarterly rate of approximately 0.4% in the fourth quarter while more modest declines of 0.2% and 0.3% are signalled for the eurozone and UK respectively. Modest growth is meanwhile indicated for Japan.

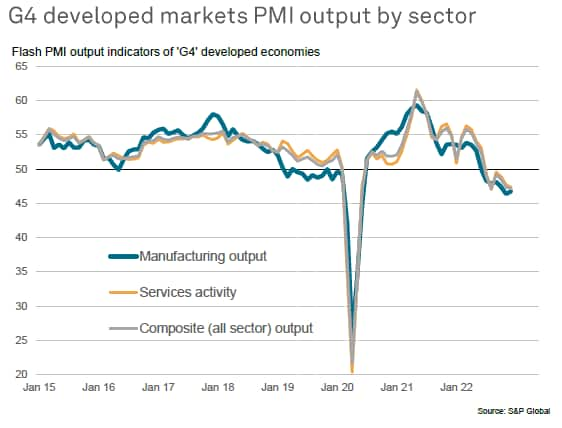

While manufacturing output fell across all G4 economies, led by an accelerating decline in the UK, service sector activity trends were more varied. Service sector output rose slightly in Japan and stabilised in the UK, with a moderating rate of decline seen in the eurozone. In contrast, service sector output fell at an increased rate in the US.

Output fell at similar rates in aggregate across both the manufacturing and service sectors of the four main developed economies, albeit with manufacturing reporting a slightly slower rate of contraction while the service sector decline accelerated slightly.

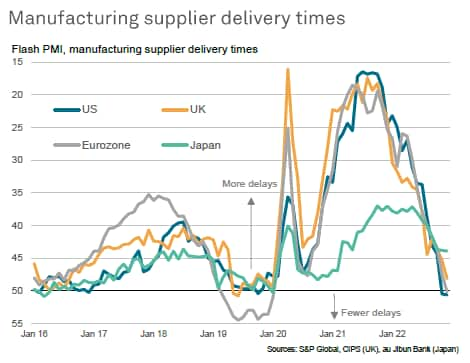

A major consequence of the downturn seen in the major developed economies, and in particular manufacturing, is the alleviation of supply chain constraints.

While the pandemic had been characterised by shipping delays and shortages of raw materials and goods around the world, this situation is now reversing. Not only have many of the logistical issues from the pandemic been resolved, but demand for many goods and raw materials is now falling. Hence supply chains are healing and suppliers are less busy. In fact, December saw average supplier delivery times shorten for a second month running the US and shorten for the first time since the pandemic began in the eurozone, led by a notable improvement in Germany. Supplier delays meanwhile also eased sharply in the UK and, to a lesser extent, Japan.

In all, the latest supply chain developments represent a major contrast to the unprecedented supply delays seen throughout 2021 and into the early months of 2022.

This combination of falling demand and alleviating supply disruptions took further pressure off prices in December, with average prices paid for inputs by manufacturers across the G4 rising at the slowest rate for two years.

A further weakening of price pressures should also be anticipated in the coming months, given the current environment of supply and demand, with the surveys generally pointing to the shifting from a sellers' market to a buyers' market, a process which is being further supported by evidence from the PMI surveys of factories moving from a position of inventory building to cost-cutting inventory reduction.

All G4 economies reported slower manufacturing input cost inflation, with the US reporting by far the steepest easing while Japan saw price inflation remain more persistently elevated.

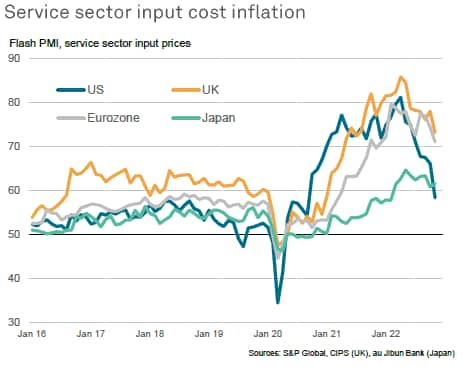

Service sector input cost inflation rates have likewise moderated in the US and in Europe, with the US seeing an especially steep decline in the rate of increase. Japan was an exception, reporting a slight uptick in service sector input cost inflation amid ongoing supply-side constraints, but these constraints are showing signs of calming in the US and Europe alongside lower energy prices.

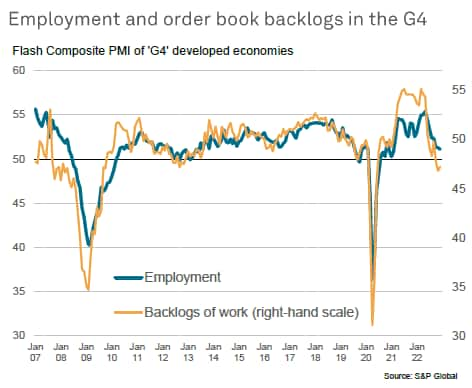

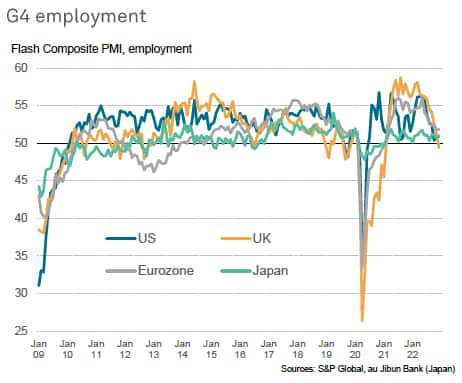

A development helping to moderation of input cost inflation, especially in services, has been a cooling of labour markets, which has taken upward pressure off wages in many cases. Whereas the pandemic had seen companies struggle to find workers, leading to a large rise in backlogs of work, these backlogs are now falling across the major developed economies at a rate not seen since the global financial crisis (excluding initial pandemic lockdown months). Hence companies are now taking a more cautious approach to hiring, with the overall rate of job creation in the G4 economies slipping further in December to only a very modest pace which was the lowest since the early months of 2021.

Jobs are in fact now being cut in the UK for the first time since the early months of the pandemic, and recent months have also seen the slowest job gains in the US and Eurozone recorded over the past two years.

The survey data are therefore indicating a major reversal of six important economic trends in the developed markets compared to this time last year.

First, output has deteriorated from a position of surging growth to registering the steepest downturn since the global financial crisis, barring only the early months of the pandemic.

Second, demand for goods and services, buoyed this time last year by the reopening of economies from the pandemic, has turned strongly negative, with spending eroded by the surging cost of living, the energy crisis (linked to the Ukraine war) and rising interest rates, as well as inventory reduction policies.

Third, unprecedented shortages fueled by a lack of materials and labour during the pandemic are now being replaced with excess supply in many instances, with increasing numbers of companies even reporting the need to reduce inventory due to the accumulation of excess stocks amid lower than expected sales.

Fourth, backlogs of work - driven up at record rates by shortages - are now falling, pointing to excess operating capacity.

Fifth, widespread demand for labour to help reduce backlogs of work is switching to a more cautious hiring approach, and in some cases, leading to falling employment.

Sixth, surging price pressures associated with soaring demand and supply side constraints are now giving way to weakening price pressures, with growing instances of discounting in order to stimulate sales and pare back unwanted inventories.

All of the above therefore suggest that an economic slowdown is leading to the build-up of disinflationary factors. There are some caveats, notably the possibility of resurgent global supply chain issues emanating from COVID-19 in mainland China and a possible spike in energy prices amid an escalation of the Russia-Ukraine conflict (or adverse winter weather). It is also possible that we are seeing some bottoming out of the downturn in Europe, though it is far from clear that the recent PMI data improvements in the UK and eurozone represents a turning point, especially as the Bank of England and the ECB continued to tighten policy aggressively (by historical standards) in December. The impact of these rate hikes, and a further rate rise in the US, has yet to feed through to the economy, posing downside risks to growth. It remains to be seen whether this aggressive stance is maintained in the coming months if the official data on economic growth, inflation and the labour markets follow the trends signalled by the PMI surveys.

For interest, so history of lagged policy responses to survey data, and misleading signals from official data at key periods of policymaking, can be found here.

Case study: PMI data sent early signals of GFC impact on Eurozone GDP | S&P Global (spglobal.com)

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, S&P Global Market Intelligence

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

© 2022, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.