Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY — Nov 24, 2022

Flash PMI survey data for November showed the global economy coming under pressure from falling output in the major developed economies, with output declines now broad-based across the US, eurozone, UK and Japan. The current bout of economic weakness represents the steepest economic downturn since the global financial crisis, if pandemic lockdown months are excluded.

An upside of the slowdown has been a further alleviation of supply constraints and reduced upward prices pressures, notably in manufacturing but with some cooling of input cost pressures also evident in the service sector.

However, a further negative impact has been on hiring. With companies increasingly eating into backlogs of work that were accumulated during the pandemic, the business focus is shifting towards concerns over excess capacity in light of the recent demand weakness. Jobs growth has consequently slowed across the major developed economies to the lowest for nearly two years.

In their initial reaction to the flash PMI data, financial markets perceived less scope for further monetary policy tightening due to growing recession signals and lower inflationary pressures. Eyes now turn to the major central banks to see how they view the current economic situation.

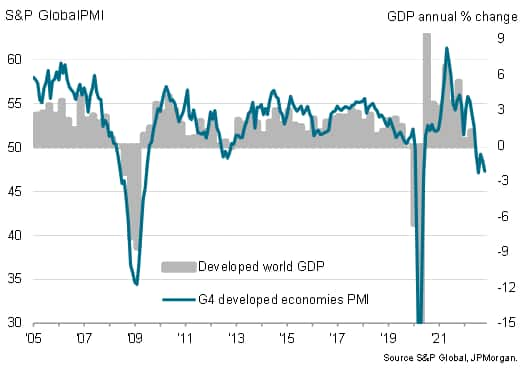

G4 developed markets PMI vs. GDP

The flash PMI data added further gloom to the picture developing over the health of the global economy. Collectively, the survey data covering the US, eurozone, UK and Japan pointed to output falling across the major rich-world economies for a fifth successive month in November. The rate of decline accelerated to the highest since August. Excluding the initial pandemic lockdowns, the recent PMI data have been indicating the steepest economic downturn for the developed world since 2009 (albeit with the current contraction falling well short of that seen during the global financial crisis).

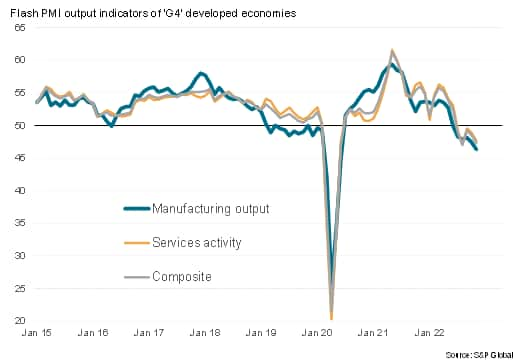

Output fell at increased rates on average across both the manufacturing and service sectors of the four main developed economies, pointing to a broad-based economic malaise, albeit with manufacturing reporting the steeper rate of contraction.

G4 developed markets PMI output by sector

The downturn also became more broad-based geographically, with Japan now joining the US, eurozone and Japan in reporting falling business activity in November. Manufacturing output fell across all G4 economies, with service sector activity also falling in the US, eurozone and UK and stalling in Japan.

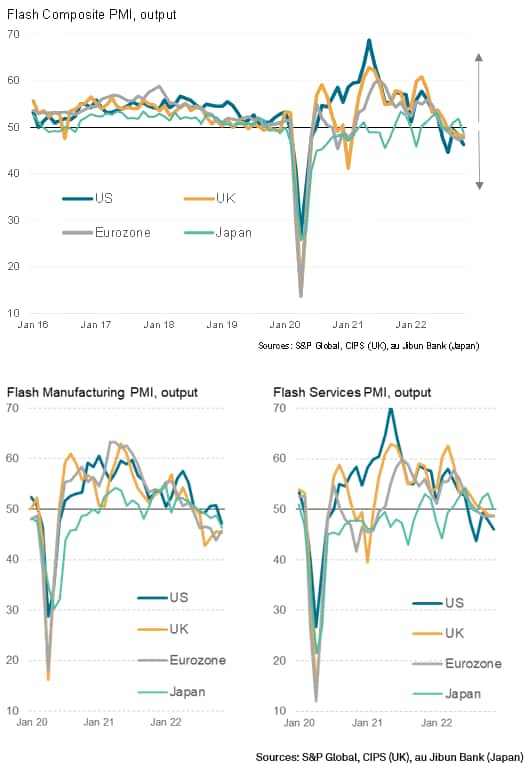

G4 developed markets PMI output

The steepest downturn in the G4 during November was recorded in the US. The headline S&P Global flash US PMI Composite Output Index registered 46.3 in November, down from 48.2 at the start of the fourth quarter. The resulting rate of contraction signalled was the sharpest since August and among the quickest since 2009, adding to survey indications that the US is mired in a period of economic downturn despite recent upbeat official data.

US GDP and the PMI

The recent PMI is broadly consistent with US GDP falling at a quarterly annualised rate of around 1% in the fourth quarter so far, albeit with the rate of decline gathering pace in November.

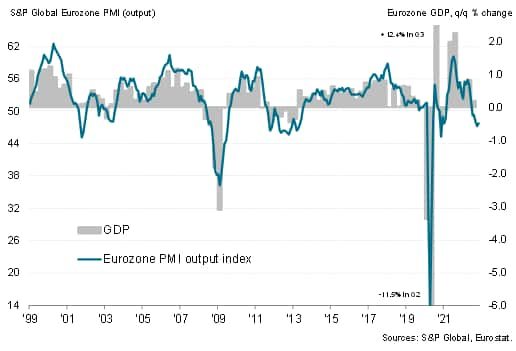

The seasonally adjusted S&P Global Eurozone PMI Composite Output Index rose from 47.3 in October to 47.8 in November, according to the preliminary 'flash' reading. The eurozone PMI has now registered below the neutral 50.0 level, indicating falling business activity levels, for five consecutive months, albeit with the latest data signalling a moderation in the rate of contraction. Nevertheless, the PMI data for the fourth quarter thus far put the eurozone economy on course for its steepest quarterly contraction since late-2012, excluding pandemic lockdown months.

So far, the data for the fourth quarter are consistent with eurozone GDP contracting at a quarterly rate of just over 0.2%.

Eurozone GDP and the PMI

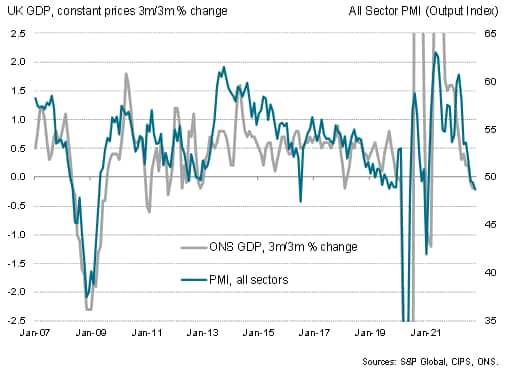

UK business activity fell for a fourth successive month in November, with the preliminary composite PMI registering 48.3 to suggest the rate of decline eased only very marginally compared to October, which had seen the steepest fall in output since January 2021 with a PMI of 48.2. As a result, if pandemic lockdown months are excluded, the PMI for the fourth quarter so far is signalling the steepest UK economic contraction since the height of the global financial crisis in the first quarter of 2009.

Comparisons with GDP indicated that the latest PMI reading is broadly consistent with the economy contracting at a quarterly rate of 0.4%. After a 0.2% GDP contraction in the third quarter, the continued decline in the closing quarter of the year would therefore indicate that the UK is in a technical recession.

UK flash PMI vs. GDP

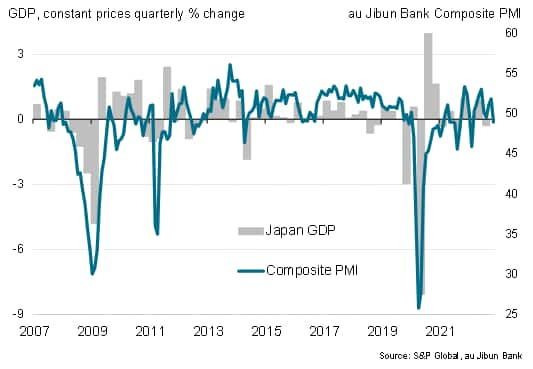

Japan joined the trend of falling output observed in the US and Europe, the au Jibun Bank PMI (compiled by S&P Global) dropping from 51.8 in October to 48.9 to register the first downturn since August and the strongest deterioration since February. A stalled service sector was accompanied by a steepening decline in manufacturing output, the latter suffering in particular from a slump in export sales.

Japan GDP vs. PMI

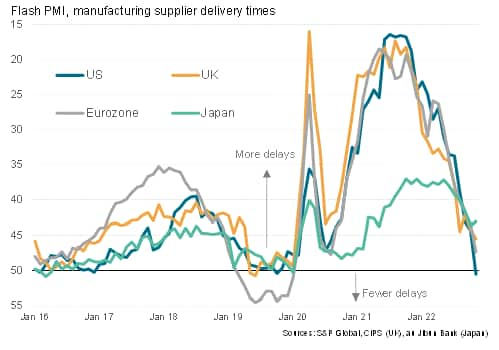

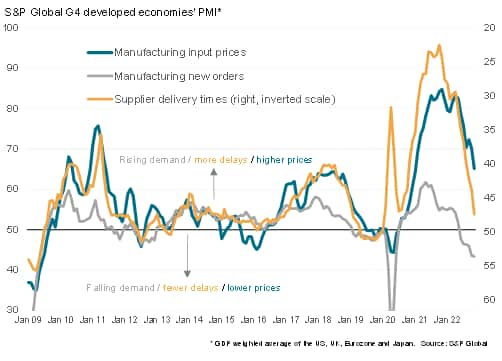

One benefit of the recent weaking of economic growth trends has been a concomitant easing of price pressures. This has been especially evident in manufacturing. On average, manufacturing new orders inflows fell across the G4 economies for a sixth successive month in November, dropping at a rate not seen outside of pandemic lockdown periods since May 2009. This reduction in demand has played a major role in taking pressure off supply chains. In November average supplier delivery times across the G4 lengthened to the least extent since January 2020, the incidence of delays falling sharply compared to October. Supplier lead-times even improved, for the first times since the pandemic began, in both the US and Germany in November.

Manufacturing supplier delivery times

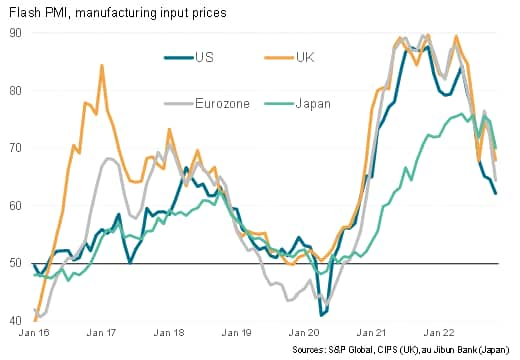

This combination of falling demand and alleviating supply disruptions helped take pressure off prices, with average prices paid for inputs by manufacturers across the G4 rising at the slowest rate since January 2021. All G4 economies reported slower manufacturing input cost inflation, with the US reporting the steepest easing.

Manufacturing input costs, supply and demand

Manufacturing input cost inflation

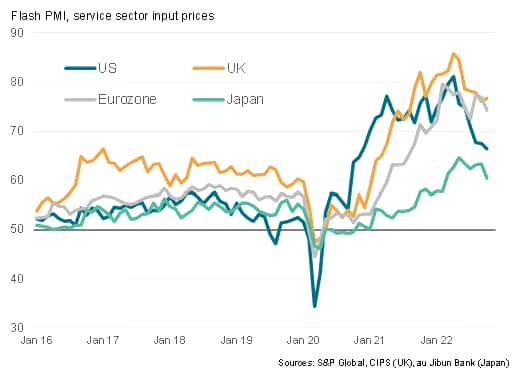

Service sector input cost inflation rates also generally cooled, the exception among the G4 being the UK, where energy and wage costs, plus higher import costs arising from the weaker pound, were widely blamed for a slight acceleration in the rate of increase. The sharpest slowing in service sector cost growth had been evident in the US.

Service sector input cost inflation

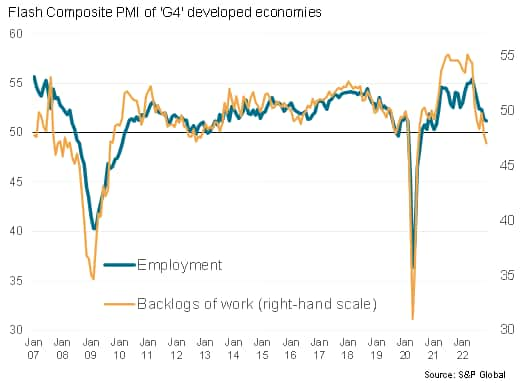

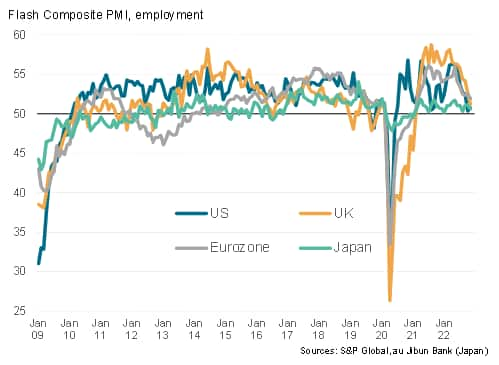

However, while softening demand has helped moderate inflationary pressures, the deteriorating order book situation has also taken a toll on employment in recent months. The lack of new orders meant firms across the G4 ate into their backlogs of previously-placed orders, which are now declining after having risen sharply during the pandemic. Companies, mindful of an unwanted build-up of excess capacity, consequently trimmed their hiring, resulting in the smallest rise in employment across the G4 for 21 months. Jobs growth has almost stalled in the US and Japan, with only very modest gains seen in the UK and eurozone.

Employment and order book backlogs in the G4

G4 employment

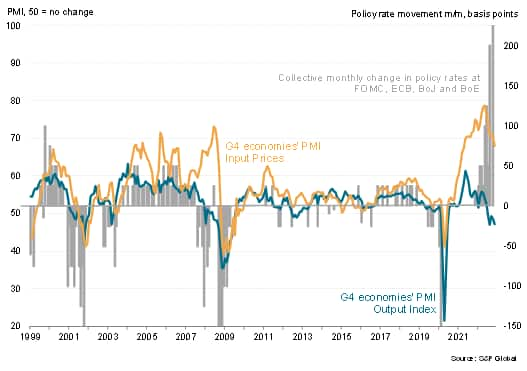

The weakening of the PMI business output and order books data, and the accompanying cooling of inflationary pressures, follow the largest tightening of monetary policy seen in recent history across the G4 economies, with super-sized rate hikes in the US and Europe pushing interest rates to their highest since 2008.

Developed economies, output, prices and interest rates

Whether these weaker PMI numbers persuade central banks that they can now apply less pressure to the economies' brakes remains to be seen, especially as many official data series continue to display surprising resilience in the face of the recent cost-of-living squeeze and tightening of monetary policy. We suspect that, as seen in 2008-9, the survey weakness has yet to fully appear in the lagging official data, suggesting there is a risk that policymakers could be tightening further into a recession, which could trigger a deeper downturn than may have been necessary to quash inflation.

More detail of lagged policy responses to survey data, and misleading signals from official data, can be found here.

Case study: PMI data sent early signals of GFC impact on Eurozone GDP | S&P Global (spglobal.com)

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, S&P Global Market Intelligence

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@spglobal.com

© 2022, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.