Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

13 Mar, 2023

By Siri Hedreen

When the U.S. Congress increased the federal bounty for carbon dioxide captured from smokestacks, The New York Times published a guest essay: "Every Dollar Spent on This Climate Technology is a Waste."

The opinion, written in August 2022, refers to carbon capture and storage, or CCS, the catch-all phrase for technologies that scrub CO2 from emissions streams and sequester it more than a mile underground. According to the authors, two former developers of the technology, CCS is a "hopelessly uncompetitive" greenwashing campaign of the fossil fuel industry.

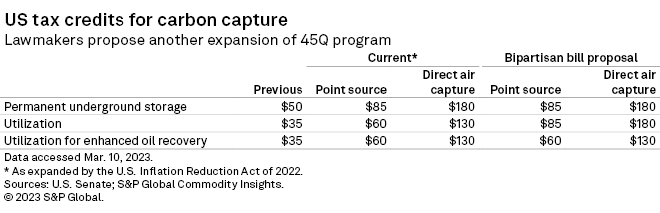

The U.S. subsidizes CCS with a tax credit, expanded by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, that awards emitters up to $85 per tonne of CO2 captured. Now, less than one year later, a bipartisan bill introduced in the Senate on Feb. 28 would further expand the 45Q tax credit program.

Once again, the backlash was swift. "This is a pro-polluter scam technology," Jim Walsh, policy director at the nonprofit Food & Water Watch, said in a statement.

"It's kind of like you just pressed the start button on the Jeff carbon capture rant," Jeff Brown, an adjunct professor at Stanford University's Doerr School of Sustainability, said when asked about the skeptics.

"You don't have to do any basic science" to deploy carbon capture, said Brown, who now leads the Energy Futures Finance Forum, which is affiliated with the think tank. "What you have to do is show Wall Street and suppliers — or regulators, in the case of the power industry — that you've done it a couple of times."

But getting the private sector to pay for first-of-a-kind demonstrations will require "generous and stable" subsidies, according to Brown's report. Unlike other decarbonization technologies, which can become a price-competitive alternative to carbon-intensive ones, carbon capture is pure cost.

And as of 2022, only 35 commercial carbon capture facilities were in operation worldwide, according to the International Energy Agency.

The Captured Carbon Utilization Parity Act, the new bill sponsored by Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., and Bill Cassidy, R-La., would increase the tax credit for emitters that sell their CO2 as a byproduct instead of storing it. At present, carbon utilization projects are eligible for up to $60 per tonne of CO2 recycled. If the bill passes, some would be eligible for the full $85.

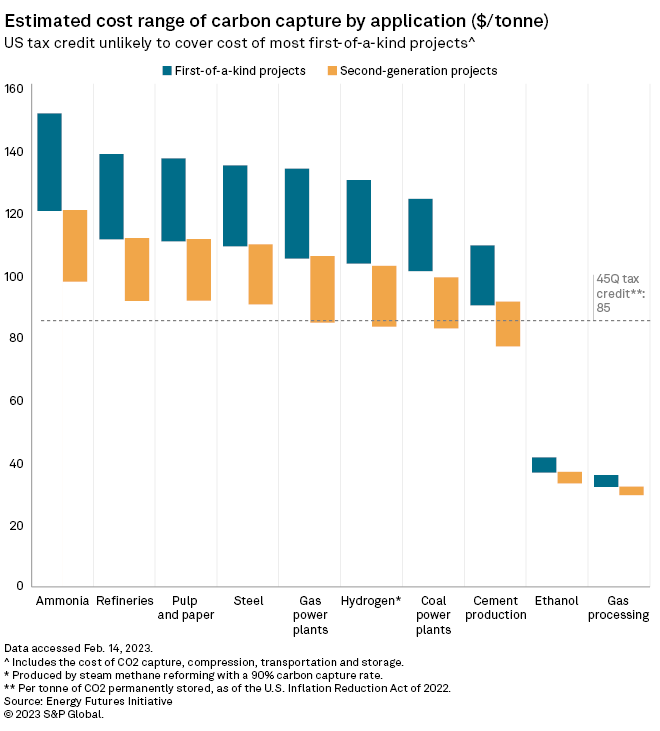

The Energy Futures Initiative report was published just before that bill was introduced, but according to the think tank's data analysis, not even $85 per tonne will cover the initial cost of CCS in most industries. Though technologies tend to become cheaper over time, CCS advocates said that without government support, companies will never innovate the decarbonization tool.

"The core problem is that in most of the world, you can freely emit your carbon pollution into the atmosphere," Ben Longstreth, global director of carbon capture with the advocacy group Clean Air Task Force, said in an interview. "And carbon capture is not something that companies will do voluntarily because it's so much cheaper to just emit pollution."

Meanwhile, a few ill-fated early demonstrations have gained notoriety in the power sector, tarnishing carbon capture's reputation as a whole. One project to build a "clean coal" plant in Kemper County, Miss., was abandoned before it ever generated any electricity, forcing Southern Co. subsidiary Mississippi Power Co. to write off $6.4 billion in project costs.

And a 2021 audit found that the U.S. Energy Department spent nearly $700 million on unsuccessful demonstrations, including Petra Nova, a carbon capture facility paired with NRG Energy Inc.'s W.A. Parish 5-8 coal-fired power plant.

Instead of burying the carbon underground, NRG sold the CO2 to nearby oilfields where it was injected into depleted wells to extract more crude. But Petra Nova was frequently offline due to forced outages and CO2 pipeline shutdowns before the power producer shuttered the carbon capture part of the facility in 2020 when a plunge in oil prices rendered enhanced oil recovery uneconomic.

CCS advocates pointed out that Petra Nova's downfall was not the carbon capture technology itself but external factors. Bloomberg News reported in February that the new owner of the plant, JX Nippon Oil & Gas Exploration Corp., plans to restart the project.

The catch is that whatever CO2 Petra Nova saves from escaping into the atmosphere will only be used to extract more CO2-emitting oil from the ground. Indeed, the majority of successful CCS projects are linked to the production of fossil fuels, either through enhanced oil recovery or by being applied to refineries, according to a 2022 study from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

Ethanol and gas processing are also where CCS can be added most cheaply, for as little as about $30 per tonne, the Energy Futures Initiative found. In both applications, the capture of CO2 is an essential step in the industrial process, leaving transportation and storage as the main costs of decarbonization. As a result, the 45Q tax credit has supported a raft of CO2 pipeline projects under development in the U.S. Midwest, where ethanol is produced.

Despite the downstream emissions of ethanol and gas processing, carbon capture hawks point to the maturity of CCS in those industries as proof of concept.

Applying "old school" carbon capture to other industries as a decarbonization tool will require some tinkering, Brown said. He likened CCS to a drill. "If I take a drill with a wood bit in it and then try to drill concrete, it doesn't work," Brown said. "It's not the drill's fault. It's not that drilling is a stupid technology."

Bruce Robertson, author of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis study, pointed out that even the CCS demonstrations that nominally succeed often fail to meet target capture rates.

"The fact is that most of these projects don't succeed," Robertson said in an interview. "And that's really the key point."

Instead of trying to improve the technology, Robertson urged policymakers to consider the opportunity cost of CCS subsidies.

Building a case for carbon capture

CCS supporters concede that the tool is not a universal good.

"I think it is actually a very good thing to be skeptical of CCS," said Jack Andreasen, a manager at Breakthrough Energy who focuses on carbon management policy. "Each CCS decision should be evaluated on the merits of the project, including whether there are viable alternatives to reduce or eliminate emissions."

Proponents point to "hard-to-decarbonize" heavy industries, such as steel and cement production, as the most obvious candidates for CCS investment. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change lent credibility to CCS in its latest report, which concluded that investing in the technology is needed to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

"All the serious modeling efforts to decarbonize the future make use of the broadest toolkit possible," Longstreth said.

Even CCS in the power sector is worth evaluating on a case-by-case basis, according to Brown.

"If you have some rotten 200-MW coal plant that was built in 1960 with bad pollution control and poor, poor efficiency, it's just not worth it," Brown said.

Brown said the equation changes in circumstances like Japan's, which built a brand new fleet of coal plants in the wake of the 2011 partial meltdown of the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear plant. For newer plants, installing CCS technology could still be the more economic option.

Yet another factor is whether the CCS technology is retrofitted to scrub the CO2 from flue gas or applied pre-combustion, which is more efficient but comes with higher capital costs, according to the Energy Department. An example of the latter is NET Power LLC's proposed natural gas plant in the Permian Basin, which would capture the CO2 produced from gas-fired combustion and store it underground.

S&P Global Commodity Insights produces content for distribution on S&P Capital IQ Pro.