Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

7 Dec, 2022

By Lauren Seay and Gaby Villaluz

Investors are not the only ones worried about mounting unrealized losses in U.S. banks' bond portfolios.

Regulators are paying more attention to the accounting marks that banks are taking as higher interest rates have pushed their securities deep into negative territories. The issue has regulators growing more concerned that some banks will need to sell the assets at lower valuations if liquidity pressures continue to intensify, industry observers said.

While the industry as a whole faces few credit issues and banks are by and large still well-capitalized, the one risk regulators have seen is many banks' book values falling dramatically as rate increases have pushed their bond portfolio underwater, said Jeffrey Voss, founder and a managing partner of Artisan Advisors, a consulting firm for community banks and credit unions.

"It's a risk to the regulatory entities from a capital perspective that if those losses ever became realized, that the capital ratios would fall below minimum capital standards that are required," Voss said.

The majority of bonds that most banks hold are in available-for-sale, or AFS, portfolios, which must be marked to market on a quarterly basis. Changes in the values of the AFS portfolios are captured in accumulated other comprehensive income, or AOCI, and impact tangible book value.

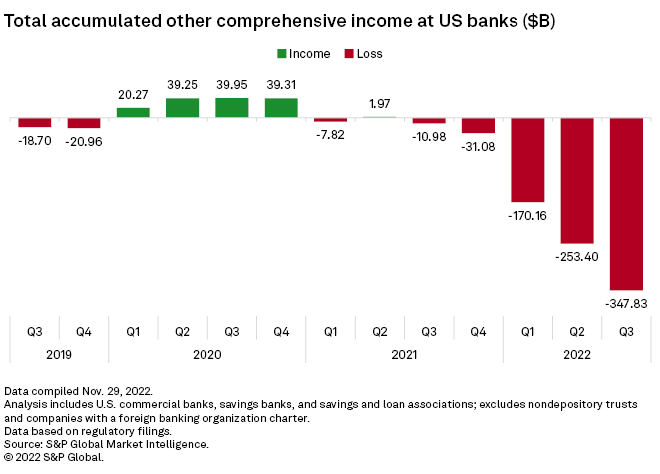

Higher interest rates have weighed on the value of bonds that banks own since they now carry below market rates. As a result, unrealized losses in securities portfolios of banks accelerated in the third quarter, and U.S. banks posted AOCI losses of $347.83 billion in the third quarter, bringing the total for the first nine months of the year to $771.39 billion, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data.

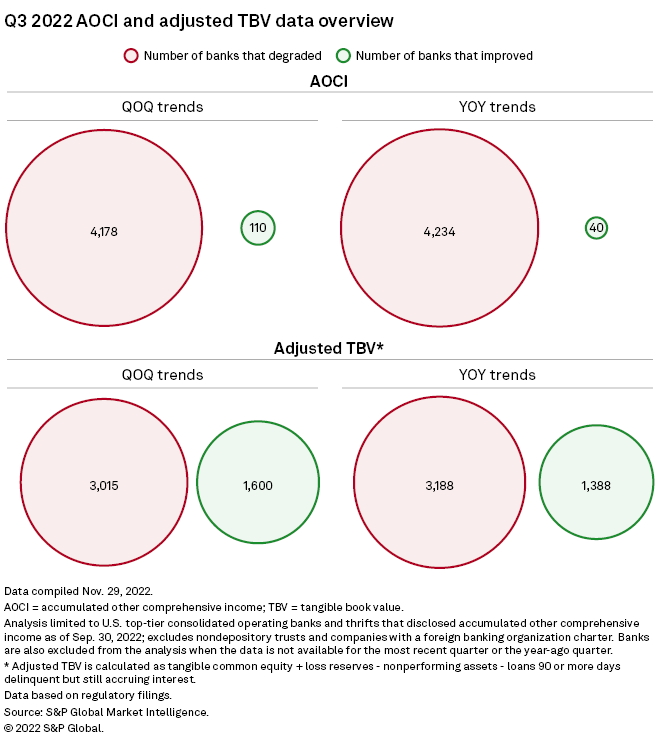

With the widespread deterioration of securities portfolios, more than 4,000 U.S. banks posted AOCI deterioration in the third quarter while only 40 posted a year-over-year improvement and 110 posted a quarter-over-quarter improvement.

The drying up of liquidity

Banks have a number of funding levers to pull if liquidity needs arise, but the drop in value of their securities portfolios makes the option of selling bonds far less appealing.

"Some of the sources of liquidity that you write down, that you probably have included in your capital plan, are not as available as they have been in the past," said Kevin Strachan, a partner at law firm Fenimore Kay Harrison.

The liquidity questions are becoming more important because banks are starting to see outflows of deposits and other funding sources are getting more expensive. Against that backdrop, regulators have questioned whether banks would need to sell securities to meet their liquidity needs. But some banks' regulatory capital ratios may not be able to withstand selling bonds at a loss.

"If you needed liquidity, what would really happen if you had to start liquidating your securities portfolio? And if the answer is 'We'd have to realize all of these losses,' then that would take their capital below well-capitalized levels. That's what regulators are worried about," Strachan said.

Kathy Marinangel, a director at Artisan Advisors, said banks will want to keep their investment portfolio intact, but some may have to recognize losses eventually.

"There are quite a few other sources that they may first go and approach, but I believe some may have to," she said.

Regulators' growing concern

The acting chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. recently voiced concerns about that exact issue.

"There's an overhang of unrealized losses on the books of our banks. That's very substantial and could be problematic, depending on how the economy evolves," Martin Gruenberg said Nov. 30 at his nomination hearing in front of the Senate Banking Committee. While banks' liquidity is currently strong, liquidity pressures could emerge as the market evolves and force some banks to dispose of those assets and turn those unrealized losses into realized losses, he said.

Just one day later, the regulator doubled down on that sentiment, saying banks may face "significant pressure" to recognize those losses.

The FDIC isn't the only agency expressing concern.

The Fed and OCC "are starting to look at this and say, 'Well, wait a minute, we've got some banks out there who have negative [tangible common equity] with just the AFS portfolio. And so we probably need to talk to anybody who looks like that,'" Rabatin told S&P Global Market Intelligence.

The Fed may want to have a conversation with banks that have a loan-to-deposit ratio close to 100% and less than 6% tangible common equity to "make sure the managements are on top of the liquidity situation and not be in a position where they have to take some sizable loss on an unrealized position," he said.

Many banks are engaging in liquidity reviews and liquidity stress tests in anticipation of upcoming regulatory exams, Voss from Artisan Advisors said. During exams, regulators will look for banks' assurance that the losses will remain unrealized and their "action steps" for potential liquidity needs, he said.

"There are action steps that banks can take like curtailing the growth of an institution's size in order to preserve capital ratios or generating liquidity through other sources," Voss said. "The FDIC and the OCC are both pushing banks to do the capital stress testing, to do the liquidity stress testing at these times. They want to make sure that the banks have tested their alternative sources of liquidity."

Regulatory consequences

If regulators have concerns about a bank's capital levels, they could ask the bank to cut back on growth or limit capital allocation toward buybacks or dividends, industry observers said.

"To be able to buy stock back is going to use up a lot of the gun powder that might be available in case of trouble times," said Craig Mueller, a managing director and co-head of the financial institutions group at Oak Ridge Financial.

The inability to pay out dividends could be particularly challenging for some S-corporation banks, Mueller said. In an S-Corp structure, shareholders are liable for the company's federal income taxes, and typically S-Corp banks cover shareholders' tax liability through dividends.

"It would hurt the shareholders," Mueller said. "It's a severe ripple effect."

Banks will not sit back

However, it is unlikely that regulators will have to force banks to address liquidity because boards are typically conservative when it comes to capital, eschewing buybacks or dividends if there are any potential issues that could arise, Strachan said.

Some banks have already begun taking a conservative capital posture, such as Puerto Rico-based Popular Inc., which announced on its third-quarter earnings call plans to pause capital deployment until the second half of 2023.

"Whether it's M&A or share repurchases, I think a lot of the banks out there are wanting to get a little better clarity on what the environment will look like in six months before they do anything with capital," Hovde's Rabatin said.

Moreover, at the moment, banks have strong liquidity levels and most should not need to sell securities for liquidity, industry observers said. Nonetheless, given regulators' focus and the potential implications of future liquidity pressure, the marks on securities portfolios are top of mind for banks during 2023 capital planning.

"It's causing a lot of heartburn here at year-end and a lot of 'How do I plan for this going into 2023?'" Mueller said. "It is one of the biggest, if not the biggest issue, certainly for the community banks, but probably for a lot of banks, going into 2023."