Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

10 May, 2021

By Carolyn Duren, Mahum Tofiq, and Liz Thomas

With Democrats in control of Congress and the White House, the concept of postal banking appears to be gaining traction.

Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, a long-time proponent of postal banking, is leading the Senate Banking Committee. Top Democratic leaders are calling for a postal banking pilot program and have previously introduced bills to establish postal banking. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., and others suggested Congress include $6 million in its appropriations bill to pilot a nonprofit banking operation run out of postal offices.

Postal banking advocates argue that leveraging the U.S. Postal Service's more than 34,000 locations to offer low-cost, basic banking services like checking accounts and low-interest loans is the best way to reach low income and underbanked consumers. It's a form of public banking that has been successful in several countries, including Japan, Germany, France and China. But opponents of postal banking believe it would create an unfair competitive environment for community banks, pitting them against a government entity with a virtually unlimited budget.

"[A postal bank] places a floor in the financial marketplace. It's a form of regulation through competition," said Mark Paul, assistant professor of economics and environmental studies at New College of Florida, in an interview. "Rather than regulating from the top down, it regulates from the bottom up, by providing everybody with access to free, safe, accessible and stable bank accounts, and being inclusive to bring them into the banking system, and really placing that reasonable floor in what we can think of as plain vanilla banking."

Some critics dismiss the need for postal banking, arguing the banking business is best left to the private sector.

"We have banks. The idea that the government is going to do a better job is just laughable," said Patrick Toomey, R-Pa., Senate Finance Committee ranking member, at a March 17 conference hosted by the American Bankers Association.

With a razor-thin margin in the Senate, Democrats in favor of postal banking are facing an uphill battle, noted Isaac Boltansky, director of policy research at Compass Point Research & Trading LLC. "The odds are still heavily against postal banking being enacted any time in the near future."

Regardless of whether postal banking ever gets off the ground in the U.S., the push for greater access to financial services is already underway, potentially changing banks' relationship with core retail customers. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. launched a #GetBanked campaign on April 6 in an effort to encourage consumers to open a checking account and gain access to lower-cost financial products. Regulators have also issued guidance designed to encourage banks to offer small-dollar loans in an effort to displace costly payday lending.

Serving the unbanked and underbanked

The primary goal of a postal bank would be to serve unbanked and underbanked Americans. An FDIC survey in 2019 found that 5.4% of Americans were unbanked. Even more people are underbanked, meaning they have some access to financial services but still used high-cost products such as small-dollar loans from payday lenders.

Commercial banks often charge high overdraft fees or require minimum balances for customers to even open accounts in the first place. These fees and balance requirements are often discouraging for the poorest of Americans. In the FDIC's survey, the cost of having a bank account was listed as the main reason people were unbanked.

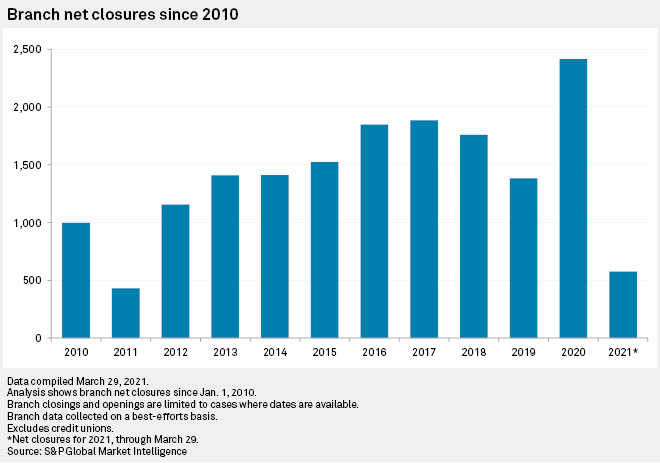

According to a study by Drew Dahl and Michelle Franke with the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, there were 1,132 banking deserts with 3.74 million people living in them in 2014. Since then, banks have continued to trim their branch networks and have only increased closures, especially since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

With a postal bank, many customers would arguably have greater access to branches. In recent years, few states have seen as many bank branch closures as Pennsylvania. If every post office in the state offered banking services, hundreds of communities would have access to financial products within a five-mile radius not currently served by a bank branch.

Sen. Brown said no-fee bank accounts backed by the Federal Reserve, administered through the post office or through small banks and credit unions, would help address underbanked individuals access lower-cost financial services. "It would show Americans how putting money, their money, in your bank or credit union can give them more power over their own money," Brown said at the ABA conference.

While a U.S. postal bank would present retail customers with another banking option, a postal bank's offerings would probably not be competitively priced, said Alex Horowitz, senior officer of the Consumer Finance Project at the Pew Charitable Trusts. It is unlikely that a postal bank would be able to offer above-market deposit rates and also unlikely that a U.S. postal bank would offer products such as mortgages, auto loans or credit cards, he said.

"It's hard to see a scenario where households with substantial deposits move their accounts to a postal bank," said Horowitz.

Pushing against going postal

Opponents of postal banking, however, do not believe brick-and-mortar locations make sense, with some arguing that the government should simply provide an online banking account. In the FDIC survey, only 14% of unbanked respondents listed inconvenient locations as a reason.

"Making banking more accessible to people doesn't lie in more brick and mortar. The trend is towards more computer access and more phone access," said Lawrence White, professor of economics at George Mason University.

Postal banking skeptics have also suggested regulators could better address underbanked individuals by encouraging or even requiring banks to provide low-cost services and help customers avoid pricey financial services such as payday loans. Policymakers are encouraging banks to get into small-dollar lending with the nation's leading banking regulators in May 2020 issuing a set of principles for responsible small-dollar lending.

"Congress or the bank regulators should require every bank to offer a low-cost, basic bank account with no overdraft fees," said Aaron Klein, senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institute. "The best solution is requiring the existing banking system to clean up their act."

Both Bank of America Corp. and U.S. Bancorp have programs for small loans, but lending guidelines for short-term loans are unclear and many banks do not want to participate in them. Even at Bank of America and U.S. Bancorp, borrowers have to have an account with the bank for a certain amount of time prior to qualifying for the loans. "You can legislate away the supply of short-term credit, but you're not going to legislate away the demand for short-term credit," said Compass Point's Boltansky.

Analogues abroad and at home

Postal banking critics often argue that getting the government involved could reduce the competitiveness of private-sector banks better suited to price credit risk. But several countries operate postal banks alongside a successful, privately operated commercial banking sector. Policymakers don't even need to look abroad for example. The state of North Dakota has its own public bank, the Bank of North Dakota, which offers retail banking services.

The Bank of North Dakota offers some cues on how a public bank can operate under the existing regulatory regime. National regulators don't regulate it, but state-level regulators examine it annually. An Industrial Commission and an advisory board of business leaders and bankers oversee the bank.

To avoid competing with privately owned banks, the Bank of North Dakota does not offer convenience items such as ATMs or debit cards. Bank of North Dakota primarily operates as a bankers' bank, financing economic development by participating in loans originated at local banks. Among its services, the bank also takes municipal deposits, provides custodial services and issues loans for agriculture and industry in the state that other banks might find too complicated.

"Big banks never liked little people, because they bring in their pennies ... and banks didn't like to bother with people like that," said Garon. But with vast economies of scale, alongside a public mission, postal banks were better able to serve these small savers.

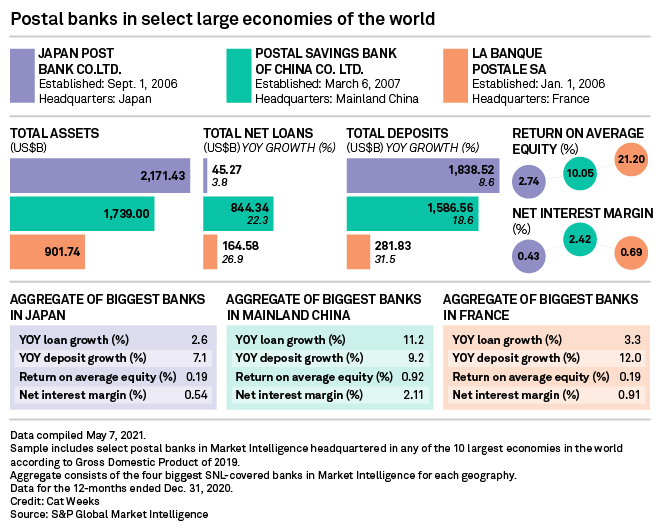

Japan's postal bank has not stopped private banks from being competitive in the country, and the four largest banks in Japan have a higher aggregate net interest margin than the postal bank. Several other countries, from Switzerland to Germany to China, also have postal banks and robust private banking sectors.

In countries with postal banks, far fewer people are unbanked, said Garon. Young people are often encouraged to open their first bank accounts with the postal bank, preparing them to have more complex bank accounts as they get older.

"It is unquestioned in the rest of the world that the combination of postal savings, plus other things like savings banks and basically small saver institutions, that these have led to nearly 100% financial inclusion," said Garon.