Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

BLOG — Apr 05, 2021

By Eva Renon

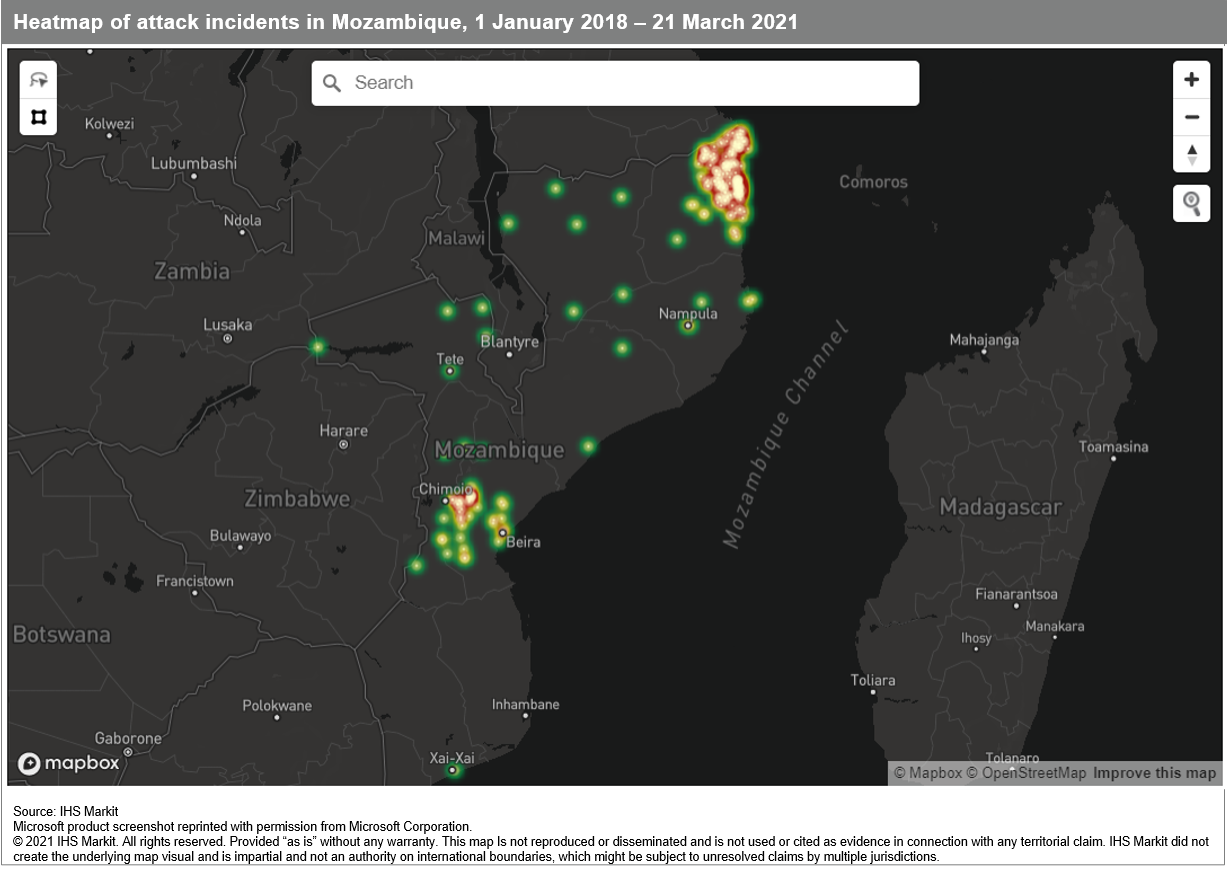

There have been two main focal points of attack incidents by non-state armed groups in Mozambique in recent years. The first, and smaller, cluster of attacks was in the central provinces of Sofala and Manica provinces and consisted mostly of road attacks along the N1 highway. These were being carried out by a militant splinter faction of the opposition Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO), known as the RENAMO Military Junta (RMJ). However, RMJ attacks appear to have ceased since February 2021 and most commanders and fighters have belatedly joined the demobilization, disarmament, and reintegration program.

The second focal point - and focus of this article - is in the north-eastern province of Cabo Delgado, where what started out as a domestic Islamist insurgency in October 2017 has since seen the fighters pledge allegiance to the Islamic State. The pace and scale of their attacks have increased notably in the past two years, with the late-March 2021 assault on Palma, and associated killings of foreigners involved in a major Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) project nearby, receiving worldwide attention.

Analytics using metadata from a large set of security incidents help to shed light on the current form of the insurgency in Cabo Delgado, and aid analysts to better forecast the future risk environment.

Islamist insurgency gains momentum

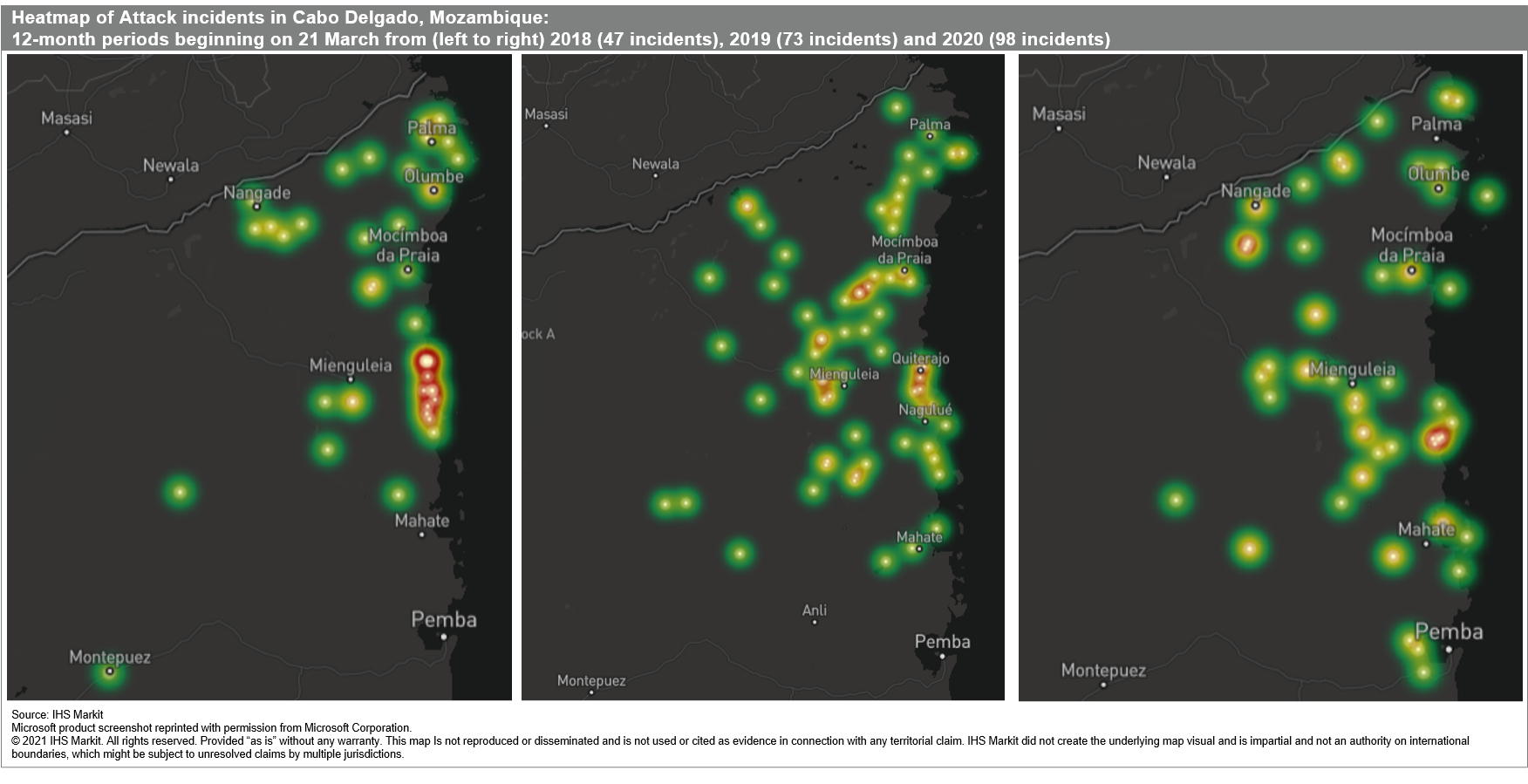

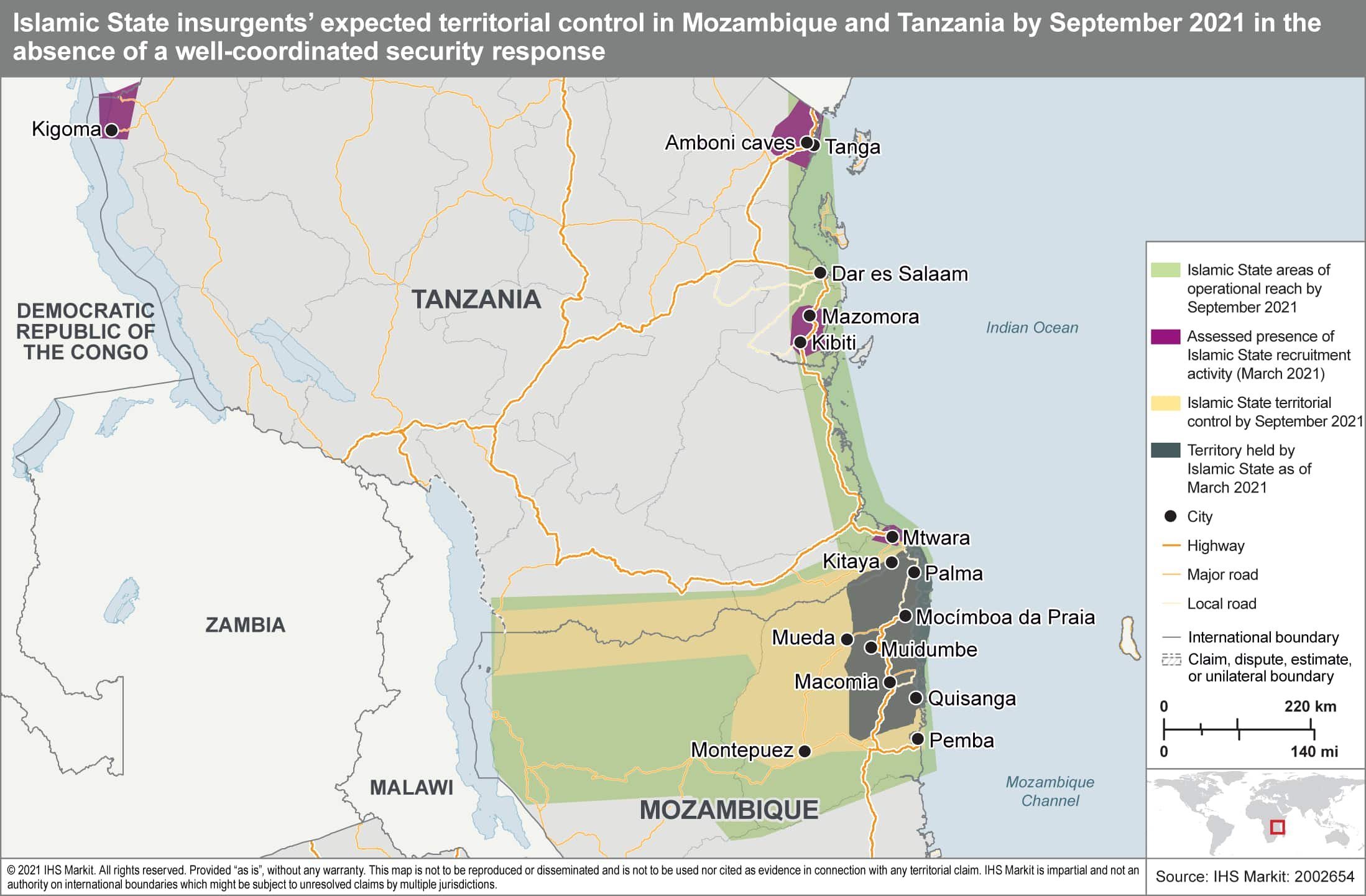

Islamist insurgents staged their first successful attack in Mozambique's Cabo Delgado province in October 2017, after an offensive by government forces against cells in Tanzania in May that year forced some fighters to migrate south into Mozambique or the Democratic Republic of Congo. Their first operation was a raid on a police barracks in Mocímboa da Praia district. Ambushes on vehicles and beheadings soon became an integral part of the insurgents' tactic set and they expanded their territorial reach by attacking new towns.

The Islamic State Wilayat Wasat Afriqqiya (Islamic State Central Africa Province: ISCAP) acknowledged the insurgents' pledge of allegiance in July 2020. The following month, insurgents captured the Cabo Delgado town and fishing harbor of Mocímboa da Praia and connected roads, thereby securing a steady revenue stream from the taxation of illicit trade in minerals and drugs prevalent there. Mocímboa da Praia has been a key transit point for narcotics for over forty years, mostly from Afghanistan and Pakistan, that make their way down to Johannesburg in South Africa, and then on to Cape Town before being shipped to western Europe, the US, and other destinations. Access to these resources has enhanced their recruitment capability, allowing them to offer relatively high salaries to disenfranchised locals. Increased revenues have also allowed the insurgents to attract defectors from the Mozambican Defence Armed Forces (Forças Armadas de Defesa de Moçambique: FADM), resulting in increased intelligence leaks from the FADM as well as greater access to arms and ammunition, while also contributing to lower morale among FADM troops.

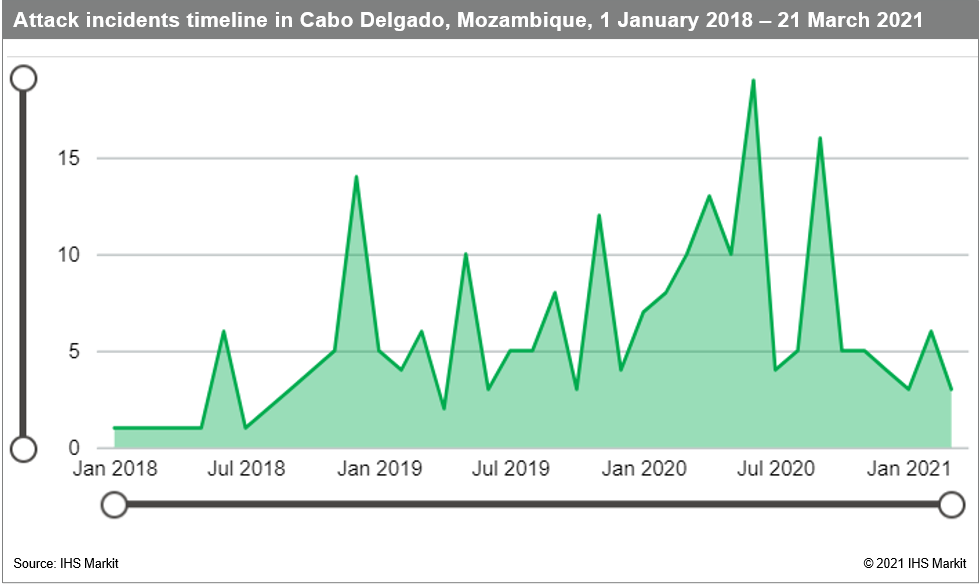

A timeline of attack incidents in Cabo Delgado shows an upward trend from early 2019. Our research indicates that this is due mainly to the abovementioned collaboration with criminal networks in Cabo Delgado and associated enhanced revenue streams.

Since the capture of Mocímboa da Praia, insurgents have expanded the territory under their control to large stretches along the main N380 and N381 highways connecting Mocímboa da Praia to the provincial capital Pemba in the south of the province. Other towns such as Macomia, Muidumbe, and, in late March 2021, Palma, have fallen under the control of the insurgents. Most of these towns have been attacked several times since 2017.

Pemba has thus far remained out of the reach of the insurgents. However, we expect to see attacks on nearby villages as a precursor to an assault on Pemba that would follow two to three months. Pemba has been a destination and a transit hub for most of the 700,000 internally displaced persons who have fled from the northern part of Cabo Delgado, along with some 2,000 employees of French hydrocarbons firm Total. All roads north of Pemba and Montepuez and east of Mueda are under the control of the insurgents and road ambushes are systematic, making the sea route from Palma to Pemba the safest.

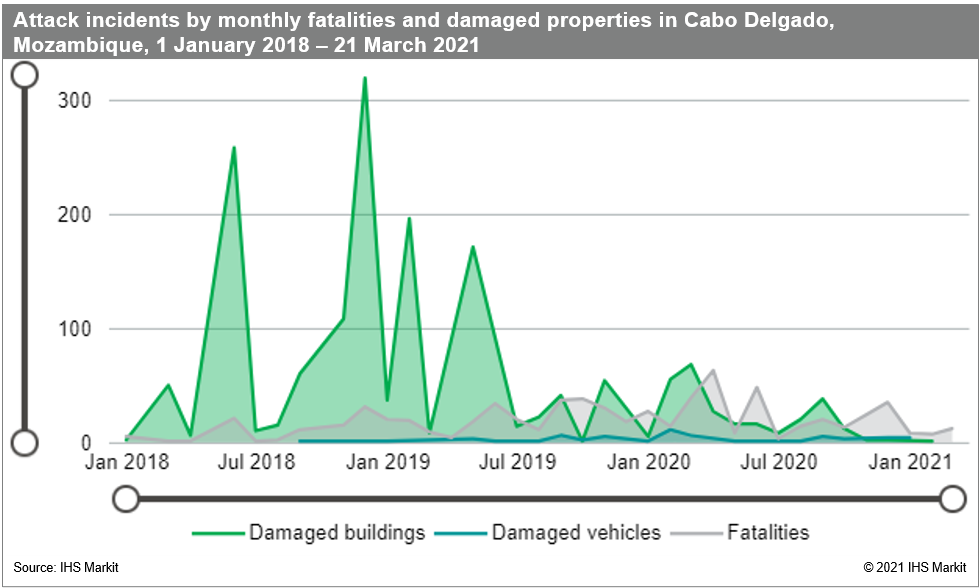

Modus operandi

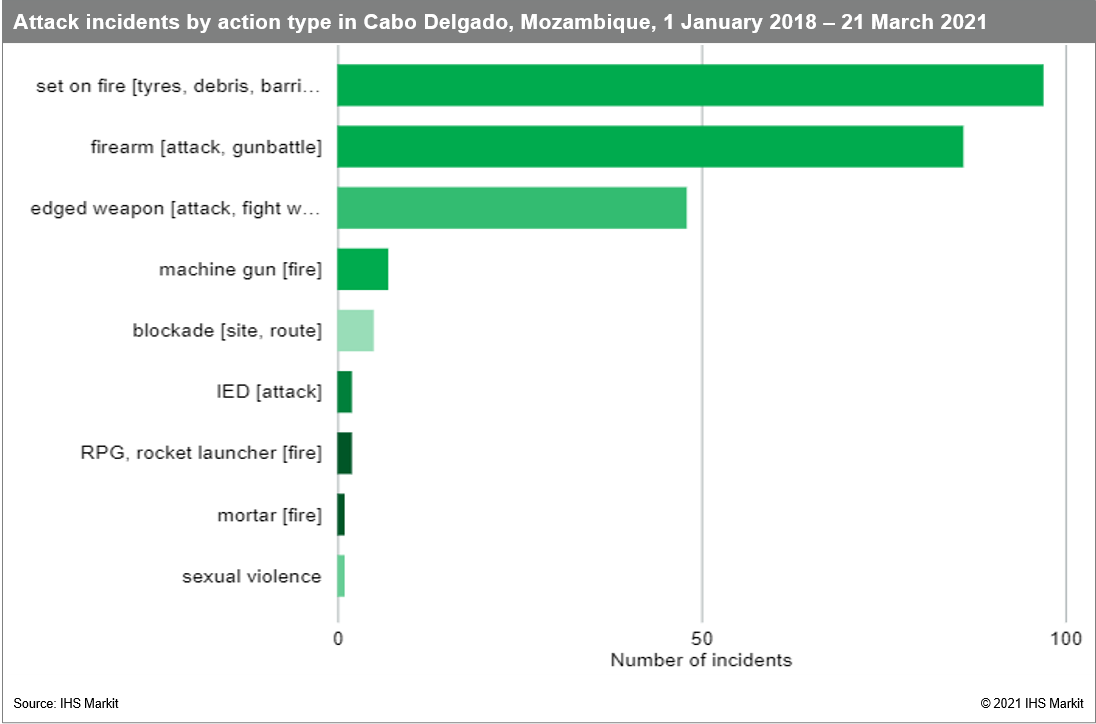

Our data shows a significant spike in the number of buildings destroyed in late 2018 and early 2019, when the most frequent form of attack was the burning of villages, often setting fire to 30 or more mud huts at a time. Since then, however, tactics appear to have shifted away from razing villages to controlling territory, increased use of beheadings, and relatively more sophisticated assaults on larger and more strategically important towns like Mocímboa da Praia and Palma.

Thus far, we have recorded only a very small number of attacks using Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) in Cabo Delgado - all against military patrols. Likewise the use of Rocket-Propelled Grenades, with only isolated cases around Mocímboa da Praia of a small aircraft carrying a Defence ministry official and a naval vessel (attacked from shore) being targeted successfully. The first reported case of the use of mortars was also in Mocímboa da Praia, during the assault against the town in mid-2020. Initial unconfirmed anecdotal reports from the March 2021 assault on Palma included reference to mortars and 'heavy weapons', something our collection team will be seeking to verify and then reflect on our incident dashboards.

Encroachment into areas of natural gas operations

The Afungi peninsula in northern Cabo Delgado is the site of Total's USD15 billion Mozambique LNG plant, which is due to start up in 2024 and eventually produce 12.9 million tons per annum (mtpa). It is also the site of the proposed ExxonMobil-operated USD25 billion, 15 mtpa, Rovuma LNG project. Eni also has a presence in Cabo Delgado.

24 February 2019 saw two attacks around 20 km from the Rovuma construction site. In one, six workers from companies contracted by Anadarko were injured. The other resulted in the death of a contractor working on an aerodrome for the LNG project.

On 27 June 2020, a vehicle of a subcontractor (Fenix Construction Services) for the LNG project was targeted near Mocímboa da Praia, with eight employees killed and three kidnapped.

On 1 January 2021, insurgents attacked a Riot Police (UIR) station and the village of Quitunda, where those resettled to make way for the LNG project had been resettled. This was within the Total LNG project area on the Afungi peninsula near Palma, but outside of the fenced construction site. The attack prompted Total to evacuate approximately 2,000 of its staff to Pemba. Total subsequently asked the government to establish a military cordon 25 kilometers from the Afungi site and announced in late March that it was ready to start sending staff back from Pemba to the area.

However, insurgents launched a sustained attack beginning 24 March on Palma. Several dozen fatalities were reported, including some foreign nationals from subcontractors working for Total's LNG project. The attack is the largest to date in the insurgency and is very likely to have required more planning and a greater number of fighters than in previous attacks, demonstrating increased capability. Total subsequently postponed the planned resumption of its activities there.

Towards a more coordinated counter-terrorism response?

The government's response to the Islamist insurgency has thus far been weak, due largely to lack of coordination and capabilities of the police and the FADM, assisted by several Private Military Companies (e.g. from Russia and South Africa). The government has also been reluctant thus far to accept offers of any direct foreign military intervention, including from the African Union and Southern African Development Community. However, the scale of the attack on Palma has the potential to encourage the Mozambican government to accept greater coordination between its forces and the US and Portuguese forces already present in the country.

Unless the security situation changes significantly, in the next six months insurgents are likely to attempt to capture Pemba which, in addition to hosting Total staff and logistics, has an airport and container port. They will likely target beachfront hotels, government facilities, and the personnel and assets of Non-Governmental Organisations, the Catholic Church, and the United Nations.

Attacks are also likely in Mtwara in Tanzania, targeting public spaces such as the market to inflict mass casualties, or against government assets and staff. However, the insurgents would probably not be able to capture and then hold Mtwara because Tanzanian security forces are more capable than Mozambican forces and have experience in fighting Islamic State-linked insurgents.

Finally, unless the security situation changes significantly, and especially if insurgents capture Pemba, they are likely to turn their attention west to Montepuez and Balama. These areas are rich in ruby and graphite deposits respectively, with the insurgents likely to seek to extort then ultimately control mining operations, with associated risks of kidnap, injury, and death to mining staff and subcontractors.

This is the third in a series of blog posts leveraging insights gleaned from security incident metadata in dashboards from our Foresight platform, following those on Egypt and the Philippines.

Posted 05 April 2021 by Eva Renon, Senior Country Risk Analyst, Research Advisory Specialty Solutions, S&P Global Market Intelligence