Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY — Mar 01, 2024

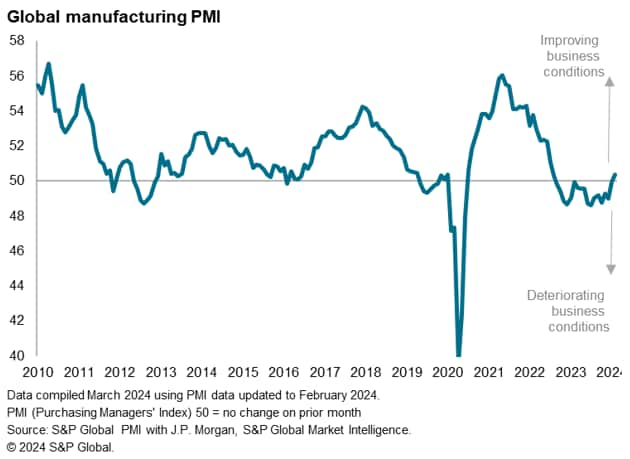

February's PMI surveys showed manufacturing business conditions improving for the first time in 18 months. The upturn provides a welcome indication that the goods-producing sector may be pulling out of the malaise it has been embroiled in after the post-COVID-19 reopening caused global demand to shift from goods to services.

The upturn does, however, signify a further reversal of the disinflationary trend that had played an important role in alleviating the post-pandemic inflation spike over the past year.

The Global Manufacturing PMI, sponsored by JPMorgan and compiled by S&P Global Market Intelligence, rose from 50.0 in January to 50.3 in February. The breaching of the 50.0 neutral level, albeit to only a marginal degree, was notable in signalling the first improvement in business conditions since August 2022.

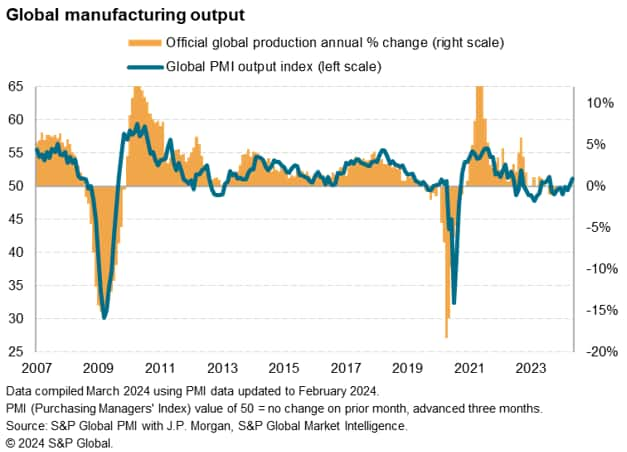

The survey's index of production hit a nine-month high, likewise heralding a revival and building on the marginal return to output growth seen in January.

Overall, new orders rose for the first time in 20 months, aided by a near-stabilizing of global export orders, which showed one of the smallest decline for two years.

The data therefore hint a recovery in the goods-producing sector from the downturn that has persisted over the prior one and a half years.

To assess what is driving this change, we first need to look at the three main causes of the prior malaise.

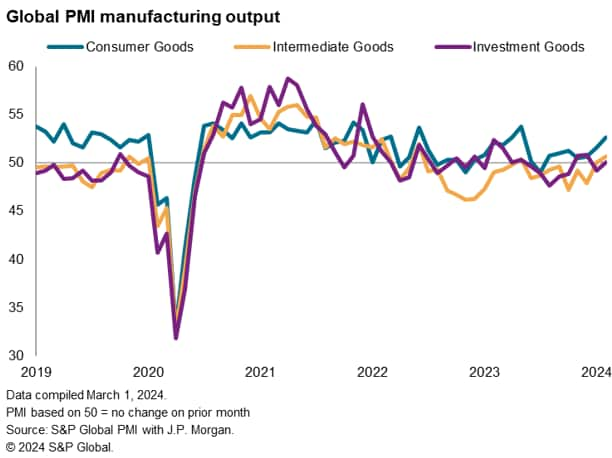

First, the fall in goods production was triggered by the shifting of spending from goods to services in 2022 as economies relaxed their COVID-19 containment restrictions.

Second, adding to the malaise has been the increased cost of living, sparked by high inflation followed by higher interest rates.

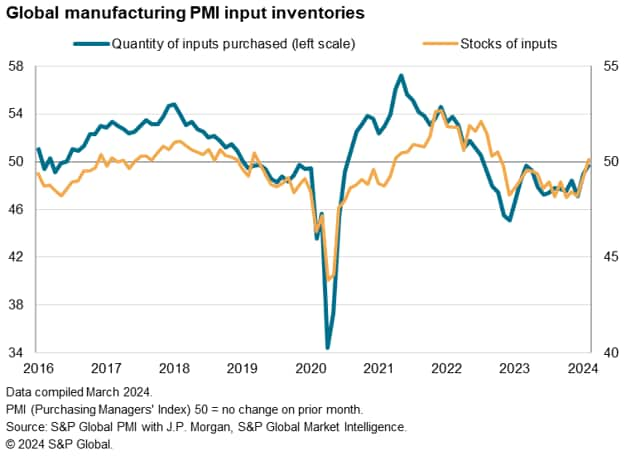

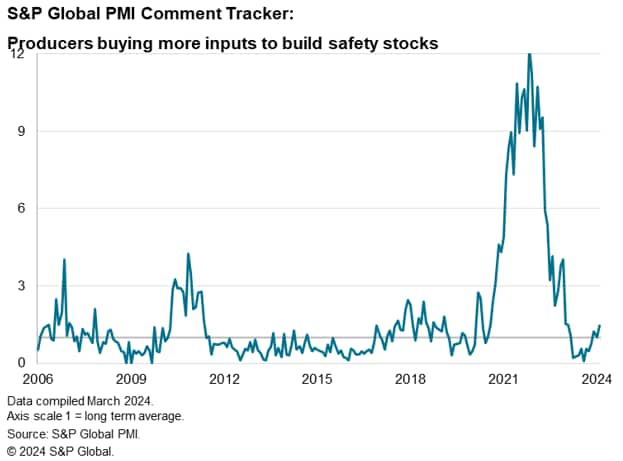

A third headwind has been a reversal of the global inventory building seen during the pandemic. Having accumulated stocks of inputs to unprecedented degrees in 2021, seeking to safeguard against supply shortages, the subsequent unanticipated fall in demand suffered by manufacturers encouraged a prolonged period of destocking.

However, these headwinds now seem to be reversing. First, consumer demand is reviving globally thanks in part to the easing in the cost of living crisis and looser financial conditions, which has been accompanied by resiliently-robust labour markets around the world; the latter was characterised by high employment and signs of returning real wage growth. The fastest expansion of global output in February was recorded in the production of consumer goods.

Second, companies are now starting to refill their warehouses. Manufacturers' stocks of raw materials rose globally, albeit marginally, for the first time in 16 months in February.

While the proportion of PMI respondent companies reporting deliberate policies of inventory reduction has been trending lower in recent months, linked to a firming of business confidence about the outlook for the coming year in recent months, it should be noted that some of the shift back towards inventory building reflects renewed safety stock building amid fears of supply constraints. The number of companies reporting that their output was constrained by a lack of inputs edged up globally to an 11-month high in February. The number of companies that reported buying more inputs for safety stock considerations hit a 12-month high. Some of this safety stock building can be linked to disruptions to shipping in the Red Sea, which has coincided with some pressure on shipping through the Panama Canal.

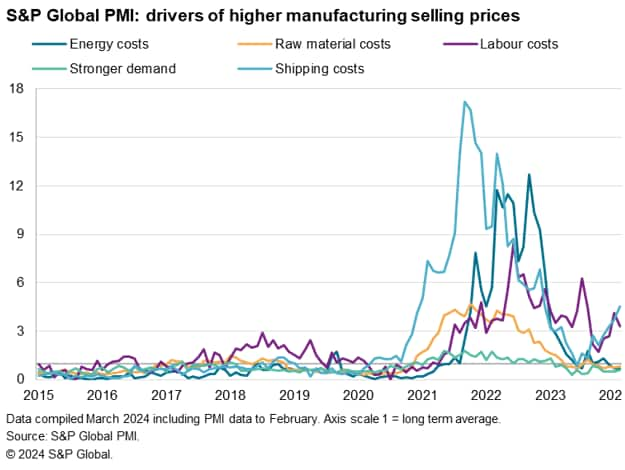

Shipping issues have contributed to further upward pressures on average global selling prices in February, and were cited by survey contributors as a key driver of price hikes alongside rising wages.

Goods prices consequently rose globally for a seventh month in February.

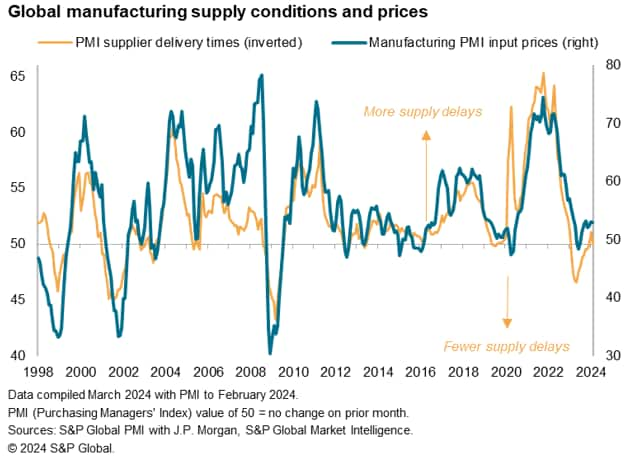

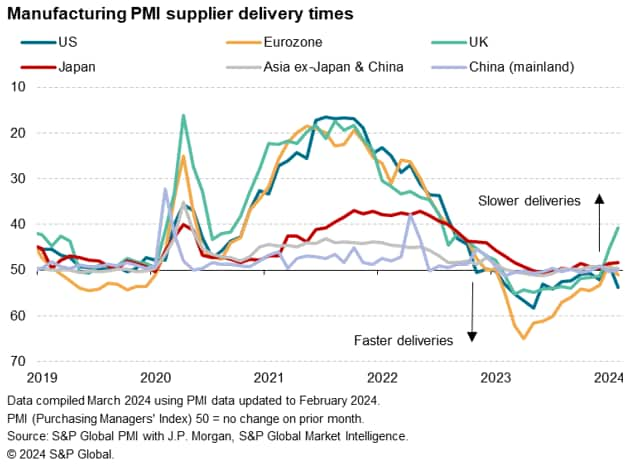

However, risks of a steep jump in prices due to the supply disruptions remains low. First, having lengthened globally for the first time in a year during January, supply chains were largely unchanged in February, even shortening slightly on average, to suggest that the worst of the Red Sea impact may already be over.

This reflects the peak disruption in late December and January, as ships were re-routed around Africa rather than passing through the Red Sea and Suez Canal. Since then, shipping has started to settle into these new trading routes. Spot container rates are hence also starting to fall again, having risen earlier in the year.

Second, the overall incidence of safety stock building remains very low by standards seen during the pandemic, though this needs to be clearly monitored.

Third, price growth remains modest, with February's global suppliers' delivery times index pointing to some alleviation of cost pressures in the near future.

It therefore seems likely that the Red Sea impact will prove fleeting in its impact on global manufacturing production and prices, albeit worthy of close monitoring in the months ahead. Furthermore, there are some economies which continued to be harder hit by Red Sea related shipping delays than others in February, with the UK notable in seeing an especially sharp rise in supplier delays. In contrast, supplier leading times shortened in the US and Eurozone, and were largely unchanged across Asia.

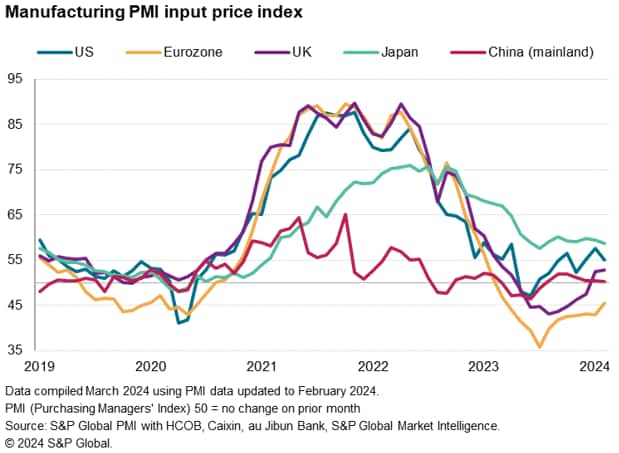

The UK therefore looks especially susceptible to some upward pressure on inflation in the coming months, its PMI manufacturing input cost gauge signalling rising cost pressures against cooling trends in the US, Japan and China and falling prices in the eurozone.

And here lies the broader concern: with central banks eager to see further progress towards sustainable achievement of their inflation targets, any reversal of the disinflationary trend for goods prices could be enough to deter policymakers from feeling confident enough to reduce interest rates.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, S&P Global Market Intelligence

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

© 2024, S&P Global. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI®) data are compiled by S&P Global for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

Location