Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY — Jan 18, 2022

PMI survey data will provide important initial insights into economic growth, inflation, supply chain and employment trends around the world, allowing policymakers, financial market analysts and businesses to assess the latest trends at the start of 2022. Here's a quick guide to some of the key issues to watch out for.

January's PMI data will provide the first broad insight into the economic impact of the Omicron variant across the globe, commencing with the flash PMI numbers on 24th January for the major developed economies.

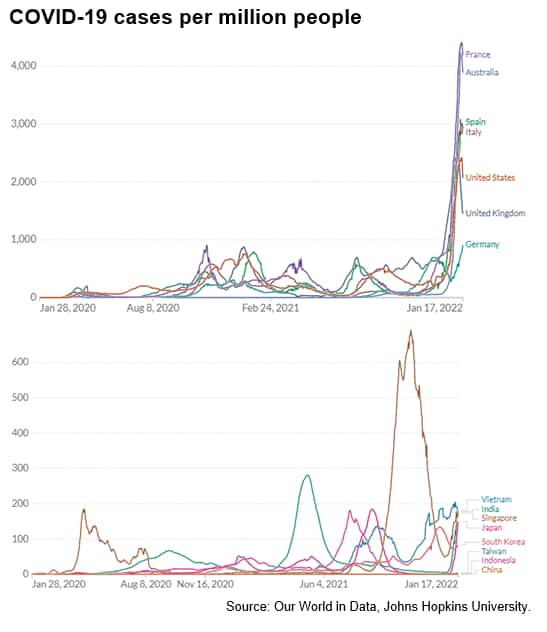

The new COVID-19 variant has certainly proven more contagious than prior waves, with case numbers spiking well above previous highs to new records in the US, Australia, the UK and all four major eurozone economies. Japan and other parts of Asia which are critical to supply chains have also been affected, albeit with lower cases per million than in the US and Europe.

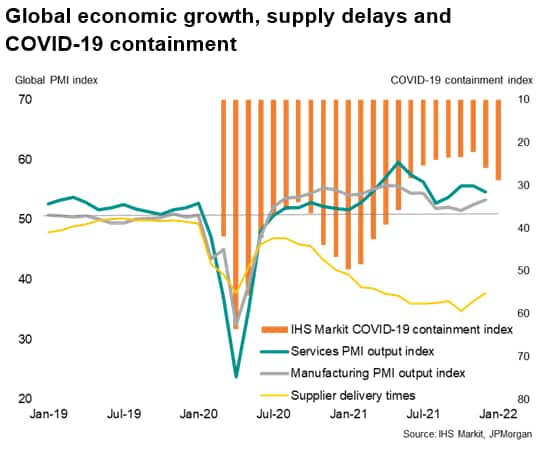

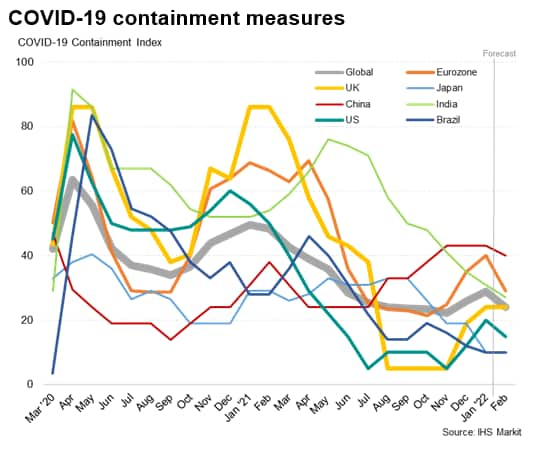

Containment measures to control the virus have been stepped up as a result, with IHS Markit's global containment index rising from 26 in December to an eight-month high of 29 in January, up from a pandemic-low of 22 in November. This containment gauge has risen especially sharply in the eurozone and to lesser, through still notable, extents in the UK and the US, and remains at the highest since the start of the pandemic in China.

The global ratcheting up of COVID-19 containment measures to the highest since last May means the PMI data will be eagerly assessed for the impact of these new restrictions on the service sector, and notably hospitality, which already suffered a subduing impact from the nascent spread of Omicron in December (PMI data were collected mid-month). Of course, face-to-face activity will also tend to be adversely affected by people voluntarily avoiding travel, venues, shops or other crowded places to safeguard against the virus, so the increase in containment measures will not necessarily provide a perfect guide to variations in national service sector performance, but should provide a useful guide.

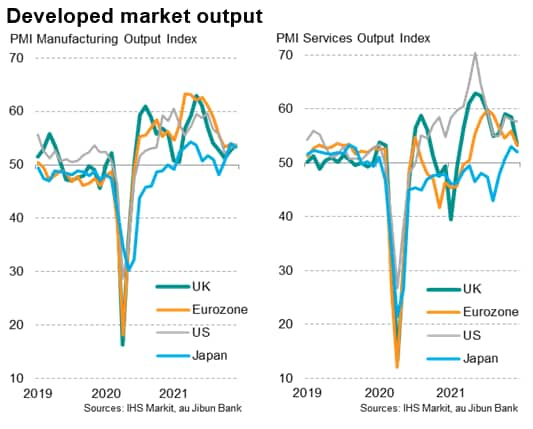

To recap, the prior PMI data showed the US leading the global expansion in December, with growth showing greater resilience compared to the UK and Eurozone, where growth rates slowed sharply. The most notable divergences were evident in the service sectors, linked to the increase in COVID-19 restrictions in Europe. Whereas UK and Eurozone overall growth rates slipped sharply to ten- and nine-month lows respectively mainly as a result of the weaker service sector performance, the US saw only a very marginal slowdown.

However, since these PMI data were collected, case numbers have risen even further in Europe, and restrictions tightened, and have spiked higher in the US to result in signs of reduced services activity. For example, averaged over the last seven days, the count of seated diners on the US OpenTable platform was 27.3% below the comparable period in 2019. Box-office revenues last week were 52.6% below the comparable week in 2019.

Japan meanwhile continued to lag, reporting slightly weakened output growth in both manufacturing and services, though continued to pull out of the Delta-wave induced downturn recorded between May and September of last year. As with the US and Europe, rising COVID-19 cases in Japan during January hint at further economic weakness in the service sector.

Any major impact on the service sector could lead to GDP estimates for the first quarter being revised lower, and could be a cause for concern for policymakers that have turned increasingly hawkish in recent weeks due to signs of stubbornly high inflation.

However, a second Omicron impact to watch for is the effect on inflation: although economic growth might slow due to the Omicron spread, the impact could be inflationary.

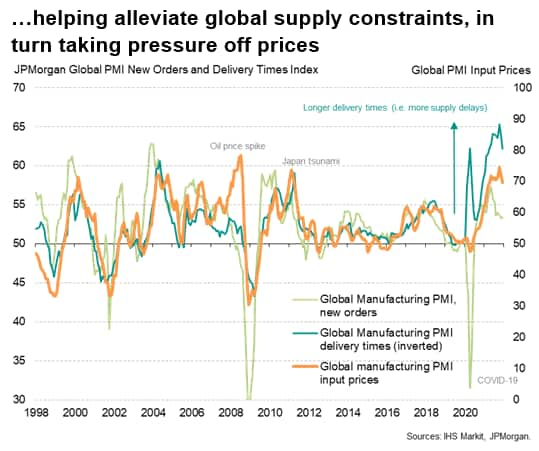

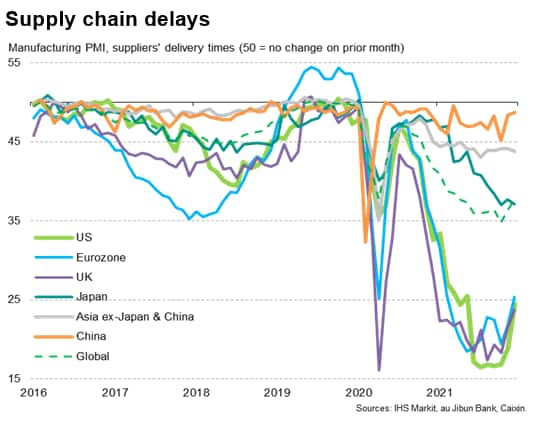

A key mechanism to watch for the feed through of Omicron to inflation is the PMI's suppliers' delivery times index. As delivery times lengthen, pricing power is handed to suppliers/sellers, and prices tend to rise. Global supply delays had shown signs of easing in December from unprecedented levels earlier in the year, albeit with delays and shortages remaining widespread, in part thanks to reviving factory output in many parts of Asia (which had been hard hit by the Delta variant), notably the ASEAN economies.

Manufacturers' input cost inflation had cooled as a result. Measured globally, input costs rose in December at the slowest pace since last April, hinting that the rate of increase peaked back in October. It should nevertheless be noted that, although moderating, the rate of input cost inflation remains higher than at any time seen in the ten years prior to the surge seen in the pandemic. As the following chart also clearly implies, any renewed lengthening is likely to lead to higher prices, especially if combined with renewed constraints on manufacturing output due to Omicron occurring at a time of stronger demand.

One of the aspects of the pandemics waves has been a switch from spending in services to goods when infection rates and containment measures increase, so it is possible that we will once again see manufacturing output constricted again just as demand for goods rises.

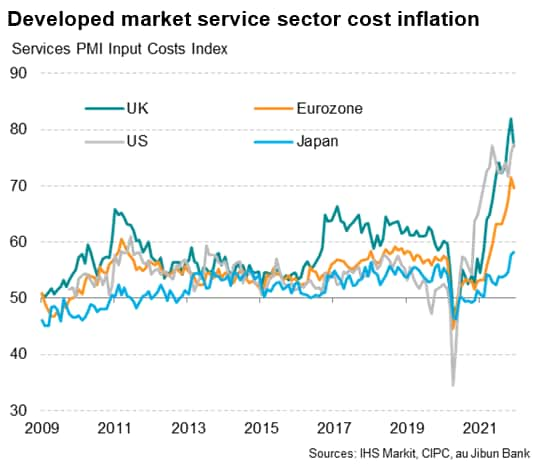

A further aspect of the surveys to watch is the feed through of price hikes to the service sector and wages, as second-round inflation effects such as rising wages could be key to the degree of policy tightening we see over the course of 2022 from the major central banks. The alleviating supply crunch has principally helped reduce the rate of manufacturing cost pressures, but a far smaller easing in service sector's price gauges was evident globally in December, reflecting the sector's greater exposure to staff costs.

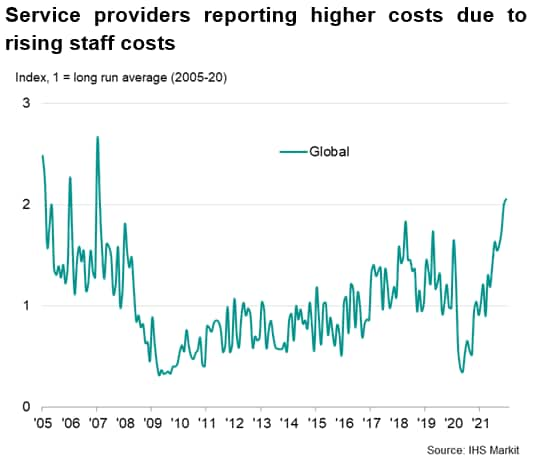

Global employment growth slowed to a three-month low in December, in part reflecting ongoing problems in recruiting or retaining suitable staff, often resulting in higher wages and salaries, notably in Europe (especially the UK) and in the US. The number of service providers reporting increased costs due to rising staff wages and salaries hit the highest since 2007 globally in December, helping sustain global service sector cost inflation at a rate only slightly shy of November's 13-year high.

The following links provide further information both on recent PMI survey findings and some of the methodology behind the surveys:

Chris Williamson

Chris Williamson

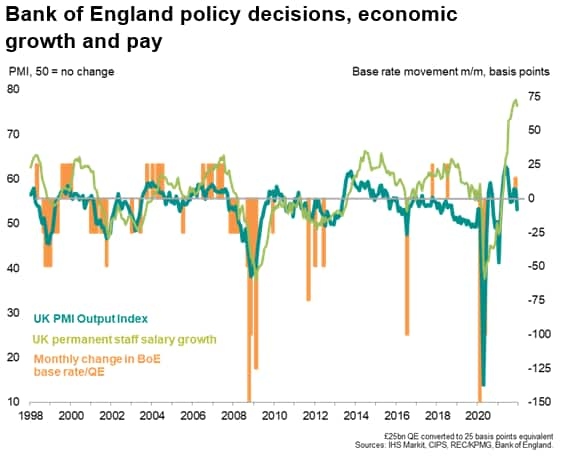

The latest UK recruitment industry survey data highlight the difficult choices currently facing policymakers at the Bank of England.

UK inflation has already risen to a decade high of 5.1%, and soaring utility bills look set to drive the cost of living higher in coming months. The Bank is pencilling in 6% inflation by April. The Bank's concern is that inflation expectations are rising, which could feed through to higher wage growth, meaning inflation stays uncomfortably high for longer than currently anticipated.

However, while Brexit and Omicron threaten to lead to further labour supply shortages, driving costs and wages up further, both factors are also likely to stymie economic growth. The juggling act for the Bank of England is to therefore steer a suitable course for policy among these signs of persistent inflation yet weakening economic growth.

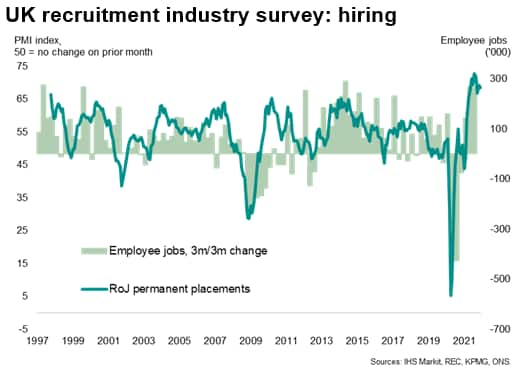

UK recruitment agencies reported a further strong rise in the number of people placed in permanent jobs in December, the rate of hiring running close to the record highs seen in prior recent months. The survey data, compiled by IHS Markit for the REC and KPMG, suggest that companies continued to take on impressive numbers of staff despite the rising spread of Covid-19 amid the emergence of the Omicron variant.

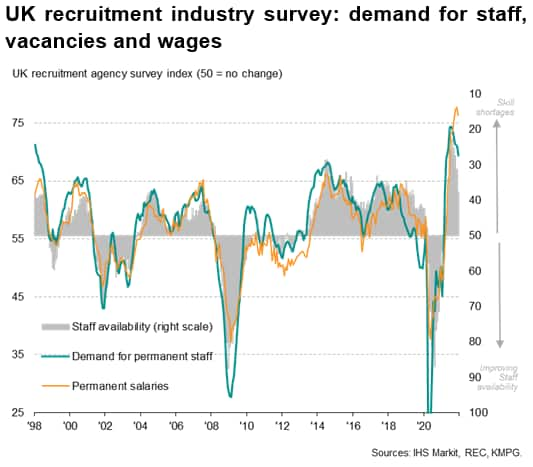

Demand for staff from employers reportedly also continued to rise at a rate not seen over the two decades prior to the pandemic, albeit with the rate of growth of demand cooling further from July's recent peak to run at the lowest since April. This latest cooling will in part have reflected lower economic activity in December arising from the omicron spread. Note that business activity, as measured by the PMI, grew at the slowest rate since the lockdowns at the start of the year.

At the same time, staff availability continued to deteriorate at a rate rarely exceeded in the recruitment survey's 24-year history, albeit below the rate of deterioration seen in mid-2021.

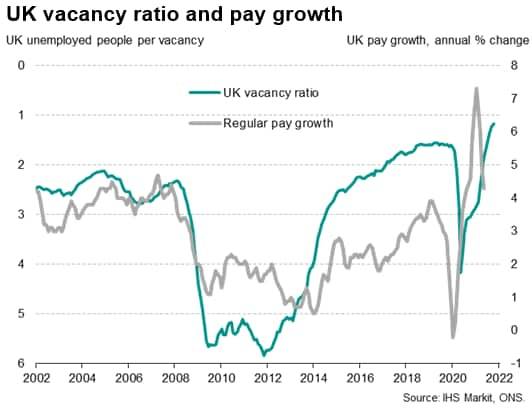

This combination of strong demand for staff and deteriorating staff availability led to a further steep rise in wages as firms competed to attract staff.

Average starting salaries and average pay for temp/contract staff rose steeply again in December. For permanent salaries, only in October and November 2021 had the recruitment industry survey ever recorded a stronger rate of wage inflation than that seen in December.

Such a lack of available staff is not surprising. The latest available official data show that the number of unfilled vacancies had risen to 1.2 million in the three months to October, while unemployment was down to 1.4 million; an implied record low ratio of job seekers to vacancies, pointing to a tight labour market which is conducive of course to high wage growth.

While higher vaccination rates mean the impact of any Omicron wave on the UK economy is likely to prove less severe than prior waves, there remain many unknowns about the severity of the variant, in particular relating to its impact on staff absenteeism due to self-isolating, illness and potential school closures, meaning the existing labour market trends of staff shortages and rising wages could worsen in coming weeks. Risks are therefore skewed towards stickier inflation and slower growth.

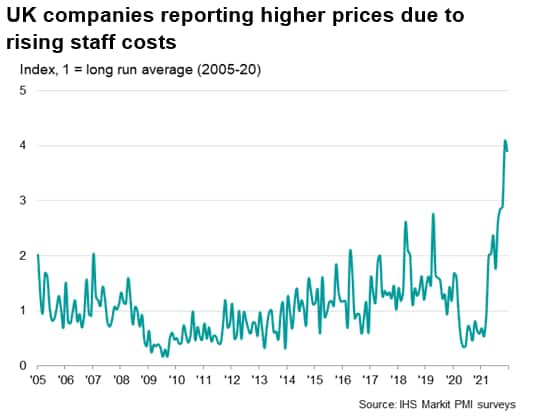

The impact of staff wages on prices is already clearly evident in the PMI survey responses. Record numbers of companies cited higher staff costs as a contributor to higher prices throughout the fourth quarter of 2021.

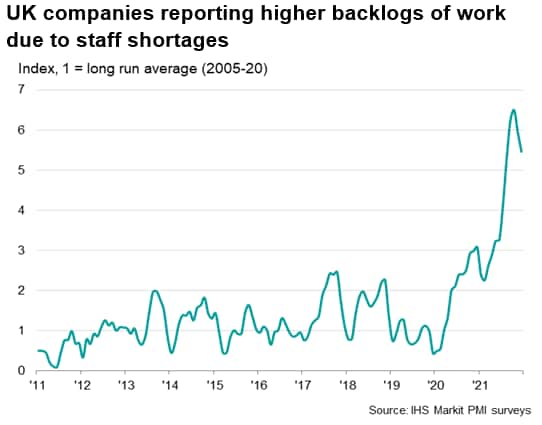

Similarly, the PMI surveys showed a further near-record number of UK companies blaming rising backlogs of uncompleted orders on staff shortages in December. Though this has likewise eased from an all-time high earlier in the year, it should be remembered that the full impact of Omicron on labour supply has yet to be reflected in these numbers.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, IHS Markit

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@ihsmarkit.com

© 2022, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

Location