Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

BLOG — Nov 11, 2022

By Janet Nodar

Wind may be the go-to renewable energy source of today, but intransigent supply chain bottlenecks will likely prevent developers from reaching "aspirational" global installation goals on schedule, according to Andrei Utkin, principal analyst with Clean Energy Technology (CET) at S&P Global.

"Many markets with favorable conditions want to move to offshore wind by the end of this decade," Utkin told JOC.com in an October interview. "Binding" offshore wind goals — i.e., targets with publicly shared government commitments behind them — alone total about 195 gigawatts (GW) to be added globally by 2030, according to CET data. S&P Global is the parent company of JOC.com.

The goal of 250 GW installed globally by 2030 probably understates demand, as it does not include countries that are planning to build offshore wind but have not committed to their targets publicly, Utkin noted. China, for example, has not made its targets public, but the country currently has about 26.4 GW of offshore wind facilities in operation, with another 47.6 GW under construction or in various stages of permitting, planning, or financing, according to CET.

As of mid-2022, only about 55 GW of offshore wind have been installed. Adding so many new GW will be an enormous undertaking, and the 2030 goal "gives the world seven years," Utkin said.

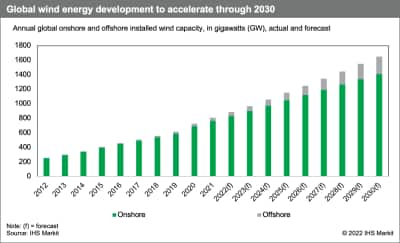

Global installed wind energy capacity is forecast to grow from 808.5 GW in 2021 to 16,707 GW in 2030.

Photo credit: Shutterstock.com

Because wind turbines — comprising blades, towers, nacelles, and foundations — are an important source of cargo for multipurpose and heavy-lift (MPV/HL) carriers, this undertaking is welcome news for project and breakbulk logistics providers, although wind energy cargoes will continue to compete for space with other project and breakbulk cargoes.

Utkin said offshore wind is the renewable energy generator of choice because it has the potential to deliver at scale, whereas alternatives such as solar struggle to provide energy at the same level, given the lack of available space and much lower load factors. While offshore wind is intermittent, it can provide very large amounts of energy, he said.

For example, Dogger Bank Wind Farm, an enormous offshore wind facility under construction in the North Sea, will have an installed capacity of 3.6 GW (3,600 megawatts) at completion, able to power as many as 6 million homes, according to the wind farm's website.

As turbine size increases, the cost of generating energy shrinks. As a result, wind turbines have grown nearly 50 percent in size for both offshore and onshore over the past five years, with vendors now selling onshore turbines large enough to generate 7 MW and offshore turbines able to generate as much as 16 MW, according to the report. A 14-, 15-, or 16-MW turbine can be up to 280 meters (870 feet) tall, and a single blade can be 351 feet long.

To put those numbers into perspective, the Statue of Liberty — from the base of the pedestal to the tip of the torch — stands 305 feet tall.

These enormous turbines are amplifying challenges for logistics service providers, particularly when it comes to the infrastructure needed to handle the transfer of cargo from port to vessel and vice versa.

"The problem is with the supply chain," Utkin said. "It's all about the size of the equipment. You have to reinforce your quays and have bigger storage facilities and spaces to put your giant towers and jackets and monopiles and plates. It's all huge."

US ports and terminals are investing millions from private, state, and federal funding to meet these needs. They include Arthur Kill in Staten Island, NY; Salem Harbor, Mass.; Bridgeport, Conn.; the New Jersey Wind Terminal; Tradepoint Atlantic in Baltimore, MD; and Avondale Global Gateway, formerly the Avondale Shipyard, on the Mississippi River near New Orleans.

However, according to a University of Delaware study published in April 2022, a one-gigawatt offshore wind project requires about 54 acres of marshaling area — i.e., staging space — over approximately two years. As such, despite planned investments, US ports will struggle to supply even half of the marshaling area needed to meet the Biden administration's goal of installing 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030. And much of the space that exists or is under construction will be in use by competitors also vying for a range of work boats and other vessels, skilled labor, and other important resources, the study said.

Worldwide, the buildout will also require many more wind turbine installation vessels (WTIVs) and foundation installation vessels, Utkin said. WTIVs are a scarce commodity, with only 18 in existence and 10 under construction at present outside of China, he said.

While there are over 40 in China, "in most of the cases these are not dedicated vessels that can install new generation turbines," he said. And these scarce global assets cannot operate as easily in the United States as they do in the rest of the world because of the Jones Act, the US cabotage law that prevents non-US-flag vessels from moving cargo or people between US ports, including between ports and offshore wind installation sites.

In Europe, WTIVs can come into port, pick up five or six sets of turbines, take them out to the installation site, install them, and repeat, Utkin said. But in the US, European WTIVs must stay at a construction site and use a feedering system that employs Jones Act vessels.

"This increases capex risk. It increases lifts," Utkin said. The only US-flag WTIV under construction at present, the Charybdis, is being built by Dominion Energy, which is developing a $9.8 billion, 2.6-GW wind farm off the coast of Virginia.

Ironically, while there is no letup when it comes to wind demand and developers' forward orderbooks are full, western turbine makers and developers are struggling financially thanks to ballooning costs for raw materials, the pandemic-induced spike in transport costs, research and development costs, and competition among themselves that is driving down selling prices, according to several mid-2022 reports from CET.

Western original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) are hamstrung in their ability to pass on rising costs as turbine prices were often agreed to well in advance of construction, and share prices for publicly traded OEMs and developers are sliding, according to the Financial Times. OEMs in China can build turbines at a lower cost and are likely to compete on price for Western manufacturers' market share, according to FT, a development that will have implications for the project logistics supply chain.

Permitting and transmission capacity present further impediments to the rapid expansion of offshore wind capacity. "All of this combined is very tough," Utkin said.

Meeting the proposed 2030 targets, both globally and in the US, will be impossible, he said, echoing the opinions of many other analysts and executives in the offshore wind industry. "Politicians like the 2030 date, but it's not going to happen," Utkin said.

Subscribe now or sign up for a free trial to the Journal of Commerce and gain access to breaking industry news, in-depth analysis, and actionable data for container shipping and international supply chain professionals.

Sign-up to Maritime Trade & Supply Chain monthly newsletter.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

How can our products help you?