Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY — May 04, 2023

A marginal improvement in global manufacturing output was recorded for a third consecutive month in April, according to the JPMorgan Global Manufacturing Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) compiled by S&P Global.

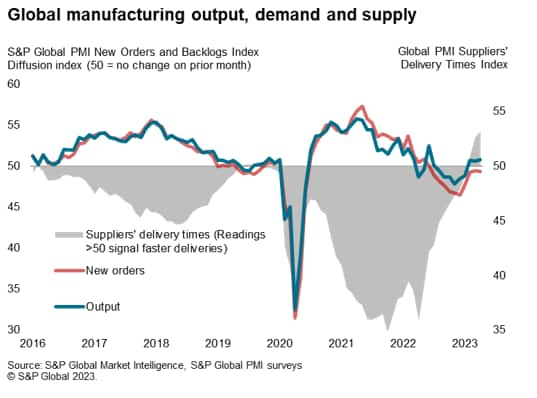

The steadying of the sector after the downturn seen late last year can be largely traced to improved supply chain conditions, with supplier delivery times shortening to an extent not seen since 2009. Better supply means production is being largely driven by the fulfillment of orders placed in prior months, which in many cases accumulated during the pandemic.

Worryingly, new order inflows continued to fall, indicating deteriorating demand for goods, in turn linked to the rising cost of living, a post-pandemic diversion of spend toward services and deliberate policies of inventory reduction.

The suggestion is that, once manufacturers have cleared their backlogs of orders, these demand headwinds will drive production lower. Manufacturers, however, are increasingly optimistic that any such slowdown will prove short-lived as these headwinds are anticipated to fade. Optimism about output levels in a year's time rose in April to the highest for over a year.

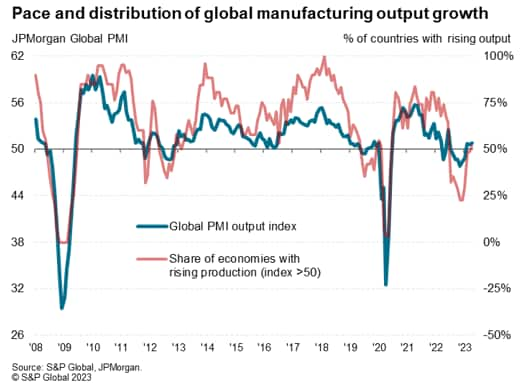

Global manufacturing output rose marginally for a third successive month in April, according to the latest PMI surveys compiled by S&P Global, contrasting with the losses incurred over the prior six months. At 50.8, up from 50.7 in March, the JPMorgan Global Manufacturing PMI Output Index remained only modestly above the 50.0 threshold which separates contraction from expansion. The recent readings are nevertheless a welcome improvement on the lows seen late last year which, barring pandemic lockdown months, had been some of the worst seen since the global financial crisis.

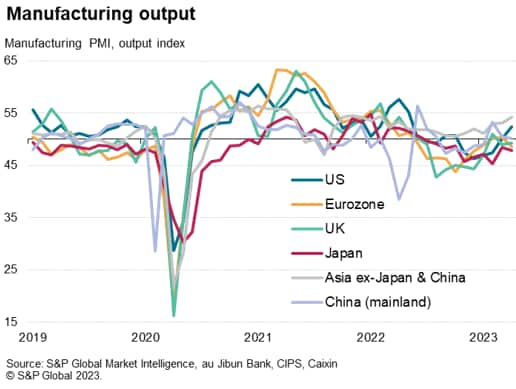

Output trends varied markedly around the world. Most notable was an upturn in manufacturing growth in the US to the fastest for 11 months, building on the marginal return to growth seen in March. Canada also saw a modest revival of growth in April.

Growth in the US was nonetheless outpaced by that seen in Asia excluding Japan and mainland China, which accelerated to a 14-month high, largely led by India.

Output growth faltered in mainland China, however, slipping closer to stagnation from the growth spurt seen in February, which had been the fastest for over two years thanks to the reopening of the economy.

Output meanwhile contracted in Europe, with both the eurozone and UK reporting falling production volumes. France saw the steepest decline of all 31 economies covered by the S&P Global PMIs, in part due to disruptions arising from strikes.

Output also fell in Japan, down for a tenth successive month.

In total, 15 economies reported falling production and 16 reported higher volumes. This compares with just seven reporting higher production volumes in the final two months of 2022.

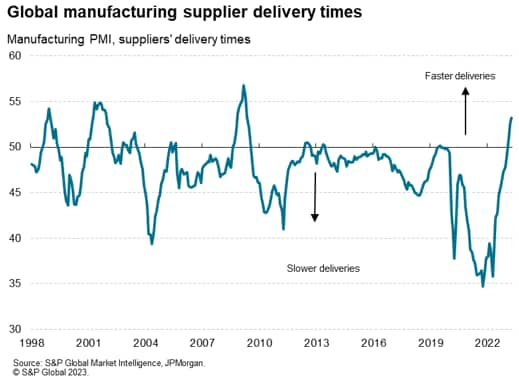

A key difference between recent months and the steep downturn seen in late 2022 lies in supply chains. Whereas 2022 was characterised by unprecedented supply chain delays associated with pandemic-related shortages of inputs, 2023 has seen supply chains start to heal. Average supplier delivery times shortened globally for a third month running in April, improving at a rate not seen since 2009.

Delivery times have improved most notably in Europe and the US, though the number of delays has also fallen considerably across Asia.

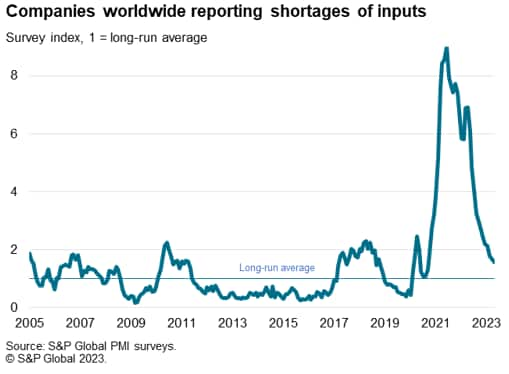

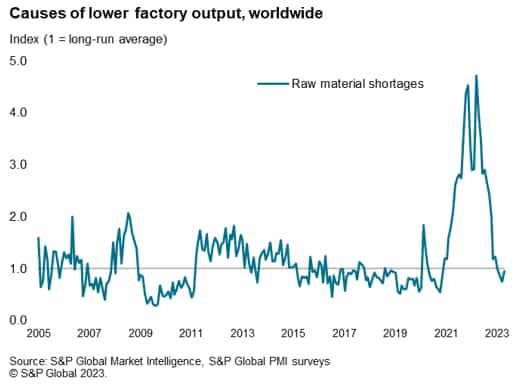

The number of companies reporting shortages of inputs has fallen commensurately. Having been running at peak of nine-times the long-run average in mid-2021, the incidence of reported shortages has since been on a downward trend such that April saw the incidence down to just 1.6 times the long run average. In essence, the number of reported supply shortages is almost back to normal levels.

Reflecting this improved supply situation, the number of companies reporting that output was constrained by raw material shortages has been running at or below its long-run average in recent months to represent to a marked contrast to the supply-driven production constraints seen at the height of the pandemic.

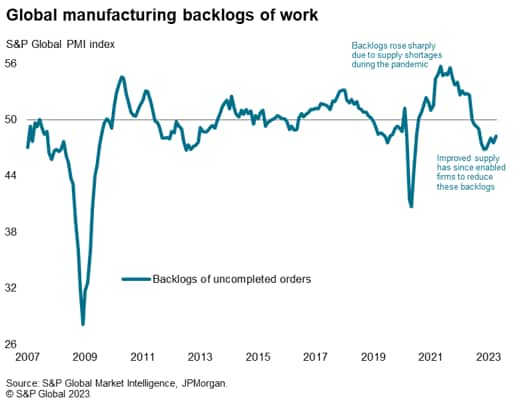

The benefit of improved supply is clearly evident in the backlogs of work data. Whereas backlogs of uncompleted orders rose sharply during the height of the pandemic amid shortages of critical inputs, these backlogs have now fallen for ten successive months, with a marked decline seen again in April.

However, whereas improving supply has helped support production through the fulfilment of back orders, demand remains a drag. New orders inflows into the global manufacturing economy fell for a tenth successive month in April. Although the rate of decline was only very modest, and far less worrying than the steep declines seen late last year, the data point to a sustained weakening of demand for goods.

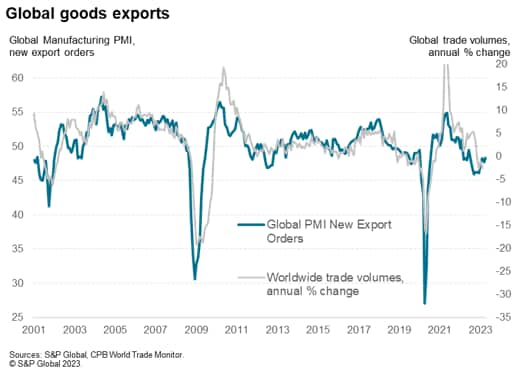

This demand downturn in part reflects a further deterioration in global trade flows in April. Global new export orders for goods fell for a fourteenth straight month.

The ongoing loss of new orders can be in part traced to the rising cost of living, which has reduced spending power across the world's major developed economies. Spending on goods has also been diverted towards services, which have seen resurgent demand in recent months following the reopening of economies after the pandemic. Travel and recreation activity, in particular, has enjoyed especially buoyant growth in recent months.

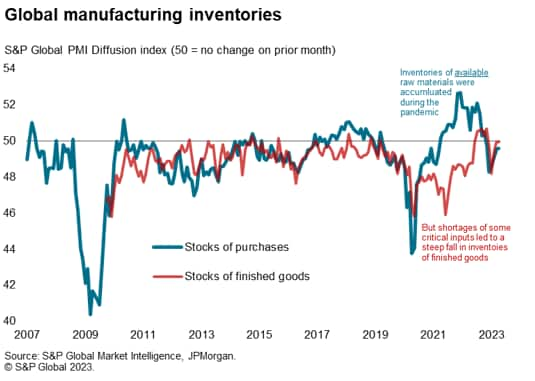

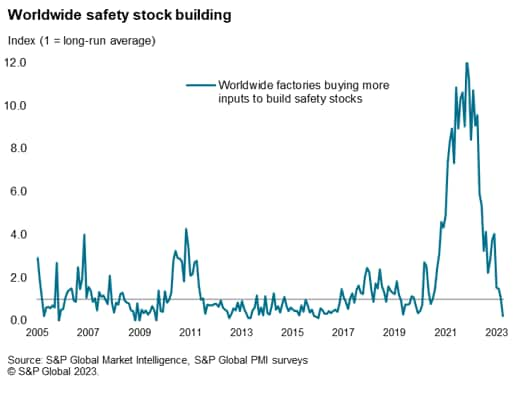

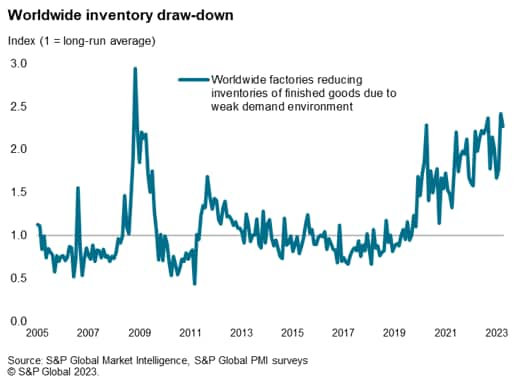

However, the drop in orders also reflected a continuing trend of inventory reduction. Inventories of goods purchased by manufacturers fell in April for a sixth successive month, in part blamed on the winding-down of warehouse stocks accumulated during the pandemic amid supply chain concerns. Worried about future supply security, factories built up stocks of available inputs during the pandemic to a degree not seen before in the PMI survey's history. Many of these input purchases are of course goods manufactured by other companies. These concerns have now faded and been replaced by concerns over escalating costs.

The worldwide incidence of safety stock building by manufacturers fell further in April to its lowest since January 2016.

It's not just inventories of purchases that are coming under pressure to be reduced. Recent months have seen historically high numbers of companies reporting that inventories of finished goods were being wound down as a result of subdued demand. The incidence of deliberate stock reduction in the face of weak demand is amongst the highest recorded since November 2008.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, S&P Global Market Intelligence

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

© 2023, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI®) data are compiled by S&P Global for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

Location