Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

BLOG — Oct 17, 2023

Following the explosion in May 2023 onboard the Pablo (IMO: 9133587), a 26-year-old tanker vessel of 97,000 deadweight tonnage (DWT) resulting in loss of life but avoiding environmental catastrophe due to being unladen, the conversation has turned again to the shadow fleet of aging crude oil tankers used to transport Russian cargo and the potential for oil spills as a result of poorly maintained vessels and a lack of safety inspections. Most recently the G7 Price Cap Coalition released an 'Advisory for the Maritime Oil Industry and Related Sectors' on 12th October 2023, highlighting concerns that vessels with unverified P&I provision for example, are a challenge to hold accountable for the heavy economic burden generated by a potential instance of environmental damage.

The issue of a potential oil spill has severe environmental and social outcomes both for local economies and marine life in general. The last major vessel-related oil spill occurred in 2018 when the Sanchi collided with the CF Crystal in the East China Sea. Since the early 2000s, vessel-related oil spills have become much less frequent. A well-maintained tanker fleet subject to regular inspections and safety overview has contributed to this but since the imposition of the oil price cap in December 2022 which seeks to restrict Russian crude to a ceiling price, a number of tankers have become carriers of Russian oil. Some of these are shadow fleet operators who originally worked Iranian or Venezuelan crude oil shipments and others who have taken an opportunity where a gap has appeared in the market to repurpose their vessels from potentially an end-of-life scenario and being broken up on a beach in Bangladesh or Pakistan to hauling Russian crude to India, mainland China and elsewhere.

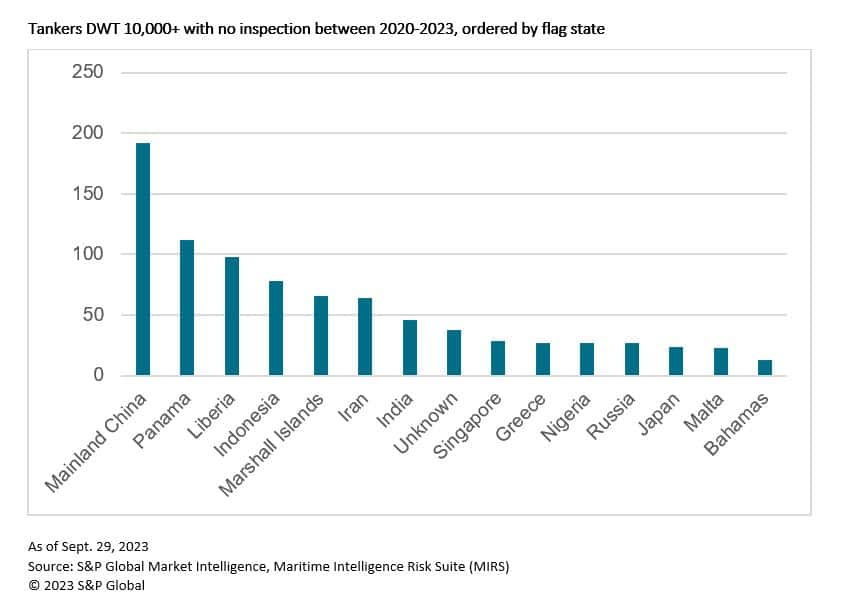

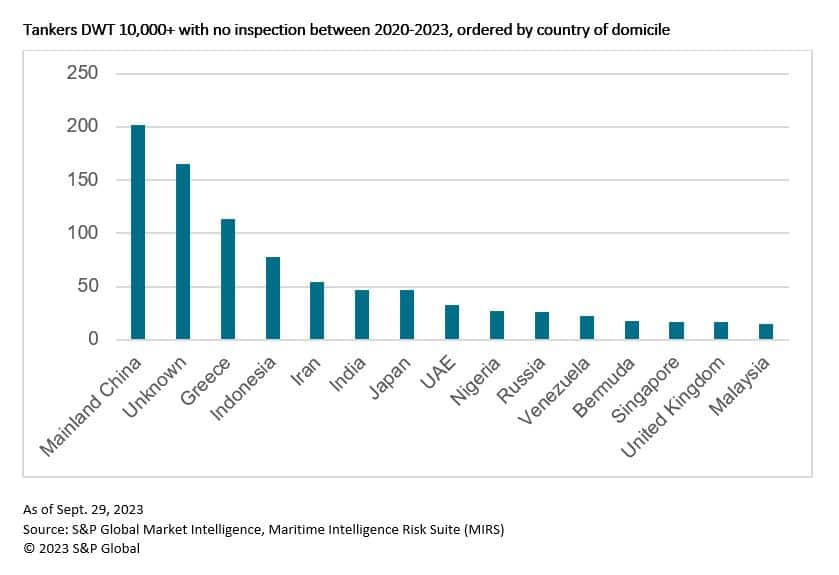

This second class of vessels and also some of those in the first category, share a similar set of particulars. Many have ownership structures in locations where due diligence checks might be of a light touch nature, they may also possess flag nationalities of a similar light touch type and in many cases the age of these vessels is pushing 20 years plus, in some instances even higher. Taking these details into consideration, the tanker fleet on the water today is of the highest age it has ever been. Together with the potential evasion of sanctions, some of these vessels have not undergone any port state control inspection or safety maintenance check for a long time. The risk this poses after 20 years of sea water corrosion, engine age and other related factors, opens the possibility of an oil spill of a large magnitude.

There are over 1,000 crude and product tankers with a DWT greater than 10,000 which have not undergone an inspection since 2020. Of this number, 530 have no P&I club association.

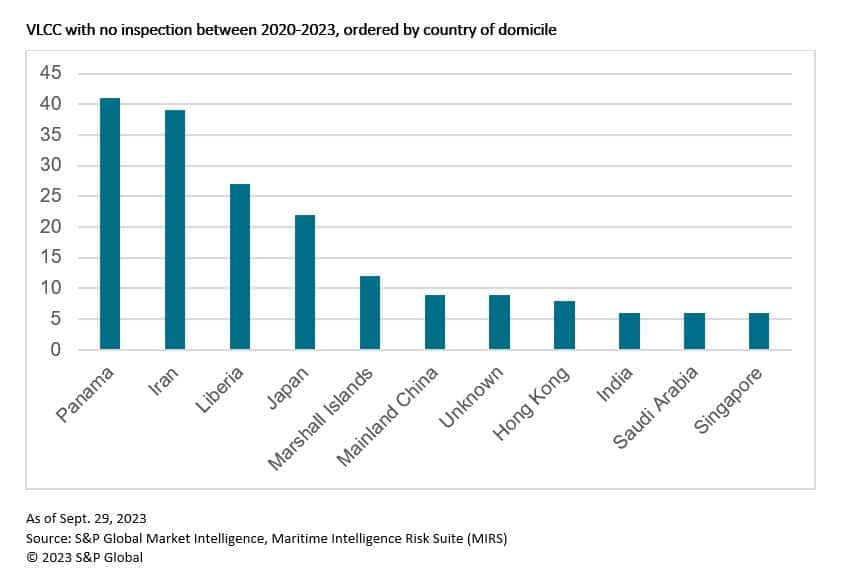

212 ships in the tanker classification analyzed above fall into the Very Large Crude Carrier (VLCC) range carrying an estimated 1.9 to 2.1 million barrels of oil on each vessel. In addition to the flag of nationality, lack of inspection and age, the size of the vessel is a cause for concern if collision or other similar action was to affect the ship.

54 of these ships in the VLCC category are 20 years or older, with the oldest at 30 years. Of the oldest top 10 VLCCs with no insurance or inspection history since 2020, 8 have no P&I club, 5 are Iranian flagged and 6 are either Iranian domiciled or unknown.

With these factors in mind, there is a risk and compliance business aspect to a potential oil spill scenario. Many firms, brokers and traders organizing the underlying trade of crude oil, banks financing the cargo via letters of credit, insurance firms with policy on the cargo and many other actors involved in the shipment have a potential reputational risk association. For traders, banks, insurers and others with complex Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) policies in place, the risk of involvement with a crude cargo on a shadow fleet vessel or a ship carrying Russian crude being involved in an oil spill creates many points of ESG failure, not to mention the associated business costs.

In the current climate, it is imperative that compliance teams treat the ownership of a maritime asset with the same due diligence approach they would to individuals and entities in order to avoid surfacing a potentially negative association. Sanctioned individuals frequently hide behind shell or front companies so as to obscure the true ownership or end user. Maritime firms apply the same attributes, often domiciled in low-risk locations and move vessels between flags and fleets often. This concealing of the group or real owner is a tactic used throughout 2022 and 2023 and was evident after ex-Russian owned ships suddenly appeared under the management of new firms such as Gatik Ship Management or Radiating World Shipping. After considerable attention was thrown onto these companies, ownership status, flag and domicile changed for these vessels. A fragmenting of the original fleets into smaller, newly established companies occurred, further removing the real owner from identification.

The circumvention tactic of multiple ownership changes in the maritime space is increasingly common. In order to keep on top of it and meet the challenge, risk and compliance teams need to deal with maritime owners as they would corporate ownership by understanding the common themes relating to the shadow fleet such as age and be aware of maritime firms relationships, for example, shared 'care of addresses' used by multiple entities and those vessels held in single ship fleets. Reducing both the likelihood and association to an environmental catastrophe also implies the avoidance of shipping owners who are unknown or hidden.

Learn more about the size of the shadow fleet, hot spots for ship-to-ship transfers of cargo, and why financial institutions should be concerned about ghost ships in our podcast, Ghosting Sanctions with a Shadow Fleet.

Subscribe to our complimentary Global Risk & Maritime quarterly newsletter, or listen to Maritime and Trade Talk podcast for the latest insight and opinion on trends shaping the shipping industry from trusted shipping experts.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

How can our products help you?