Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

12 May, 2025

By Brian Scheid

The economic impacts of US President Donald Trump's ever-evolving tariff regime appear to be forcing the Federal Reserve into a policy corner.

With the prospect of stagflation looming, Fed officials may soon need to choose between addressing the inflation expected with higher tariffs on goods from nearly all US trading partners and potentially rising unemployment as the domestic economy slows amidst the sudden shift in global trade.

"It's all about the balance of risks," said Oren Klachkin, a financial market economist with Nationwide. "This will make [Fed officials] proceed cautiously and keep them on the sidelines for now, even at the risk of acting too late."

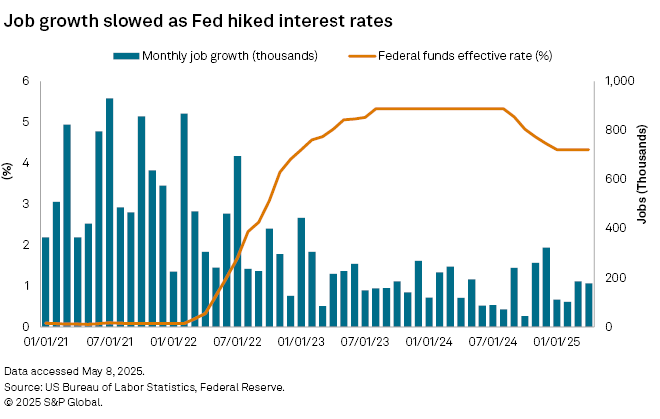

The Fed again left interest rates unchanged on May 7, with officials determining that staying put was the best course of action. With the ultimate scope and timing of the tariffs still largely unknown, the next rate cut is not expected until the fall and could be pushed back even later as the Fed waits for trade effects to start showing up in government data.

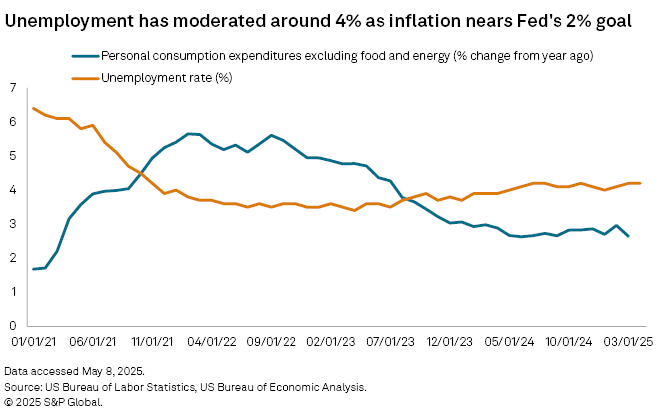

Meanwhile, the domestic jobs market remains relatively healthy, with unemployment staying just above 4% for the past year, and the annual rise in inflation showing slow, but gradual progress towards the central bank's 2% target.

Difficult position

Tariffs, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell made clear, are a considerable unknown and could upset the Fed's mandate for price stability and maximum employment. Whether the Fed will ultimately lower rates in order to address potentially rising joblessness or keep rates higher for longer to curb the anticipated rise in inflation, is still up for debate.

"We could be in a position of having to balance those two things, which is, of course, a very difficult balancing judgment that we would have to make," Powell said during his May 7 press conference.

In a May 9 speech, Fed Governor Michael Barr called the size and scope of the tariff increases "without modern precedent," and said that while their ultimate economic impacts are still unclear they could create "persistent upward pressure" on inflation, and potentially higher unemployment as the economy slows.

"Thus, the [Federal Open Market Committee] may be in a difficult position if we were to see both rising inflation and rising unemployment," Barr said.

A new calculus

The tariffs are unprecedented and the Fed's expectations and tolerance for higher unemployment could be shifting as well, according to Guy Berger, director of economic research at The Burning Glass Institute.

"I think the Fed is going to be fine with some further amount of labor market cooling in a way that they wouldn't have been pre-tariffs," Berger said in an interview. "But if they see a sudden precipitous, chaotic deterioration in the labor market that changes the calculus."

The Fed may have difficulty assessing just how temporary an increase in inflation due to tariffs might be, but could anticipate that with a weakening labor market, the inflation pass-through would be limited, Berger said.

The Fed will likely hold the line on rates, leaving the central bank's benchmark federal funds rate within its current 4.25% to 4.5% range, for as long as employment growth does not fall below 100,000 added jobs per month on a three-month average basis, according to Satyam Panday, US chief economist at S&P Global Ratings.

"They need to be convinced that weak demand growth will work to negate inflationary impulse from cost-push inflation," Panday said in an interview.

The US economy added an average of nearly 155,000 jobs over the past three months, according to the latest government data.

Economists expect an economic slowdown would push the unemployment rate toward 5%, which would likely trigger a Fed rate cut of 25 basis points or more. But the lack of clarity in US trade policy, with the level and potential timing of tariffs seemingly changing each day within the Trump administration, has created new hurdles for the Fed, confounding its ability to plan its future path for rates, said Kathy Jones, chief fixed income strategist with the Schwab Center for Financial Research.

"Without inputs on tariff levels, [the Fed] can't model what that means for the economy and inflation," Jones said in an interview. "So, it is waiting until those inputs are available and/or until something gives, such as the unemployment rate."

Economists with Goldman Sachs in a May 7 note argued that tariffs could drive year-over-year core personal consumption expenditures (PCE), the Fed's preferred inflation metric which excludes volatile food and energy prices, to 3.8% by the end of this year, its highest level since August 2023. The Fed wants core PCE, which was at 2.6% in March, to fall to 2%.

Falling inflation would making cutting rates far easier for the Fed, Jones said, but tariffs boost the risk of unemployment and inflation rising at the same time.

"It's going to be really difficult to set policy," Jones said.

The anticipated condition, inflation rising with joblessness, is one the Fed has rarely dealt with, also complicating officials' ability to plan.

"Unfortunately for the Fed, how inflation and employment interact aren't clear cut," Derek Tang, an economist with LH Meyer/Monetary Policy Analytics, said in an interview. "