Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

30 Apr, 2025

By Brian Scheid

US labor demand is slowing, with job openings down about 11% from a year ago, but it is not clear whether the job market is cooling or shifting to a new normal.

The uncertainty has taken on heightened importance as the Federal Reserve is closely gauging the health of the domestic labor market while it considers its next interest rate cut.

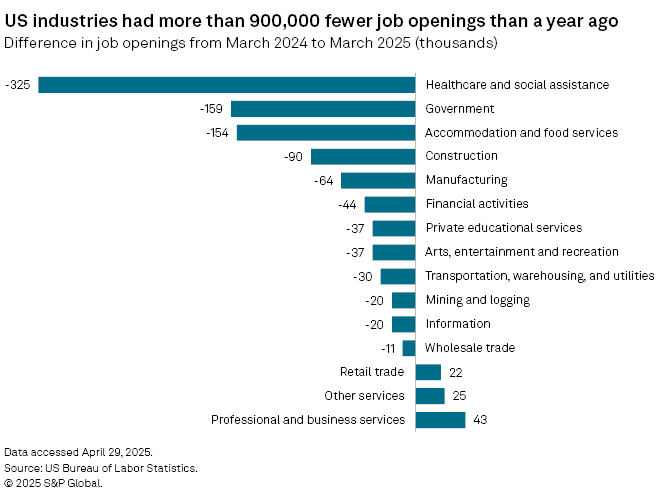

In March, there were about 7.19 million job openings in the US, down 288,000 from a month earlier and 901,000 from a year earlier, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics reported April 29. Economists said this drop is not yet a cause for concern.

"As of right now, this looks like the job market is continuing to normalize following the pandemic, rather than experiencing a policy-induced softening," said Augustine Faucher, chief economist with The PNC Financial Services Group.

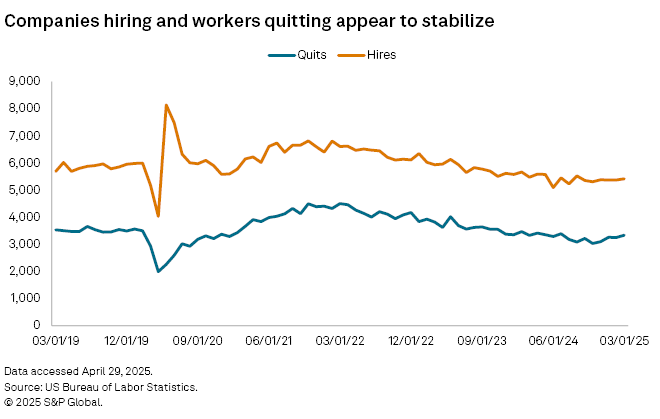

Businesses ramped up hiring in 2022 during the post-COVID-19 recovery as workers leaving their gigs for better paying jobs and new careers boosted quits rates. Labor demand has since stabilized and fewer workers are leaving their jobs, Faucher said.

"It's a cooling, but not collapsing jobs market," said James Knightley, chief international economist with ING. "Companies are scaling back their hirings, but are not looking to fire workers given a very low layoff rate of 1%."

Tariff uncertainty

While job openings are falling, they remain near where they were just months before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Hiring and turnover rates are showing signs of stabilization, and while this could signal the start of a relatively long stretch of balance in the labor market, President Donald Trump's tariff regime poses a significant hurdle, economists said.

"The April tariffs may cause serious damage to the labor market," said Guy Berger, director of economic research at the Burning Glass Institute. "So, we may look back at the March [Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS)] data as a sign of what might have been, instead of a new and welcome trend."

The data released in late April was compiled before tariff-led uncertainty spiked earlier this month. The lack of clarity over where the US economy is headed, partly due to trade policy, will mean hiring "slows from the summer onwards" and there will be "more pronounced falls in job vacancies later in the year," ING's Knightley said.

There may already be indications that labor market momentum is fading, said Cory Stahle, an economist at the Indeed Hiring Lab. The Indeed Job Postings Index, which tracks JOLTS job opening in real time, shows that job postings drop 3.8% between through the first three months of this year, Stahle said.

That decline suggests "that the stability that defined the second half of 2024 may be ending," Stahle said.

One industry seeing a significant pullback in hiring has been healthcare, the data shows.

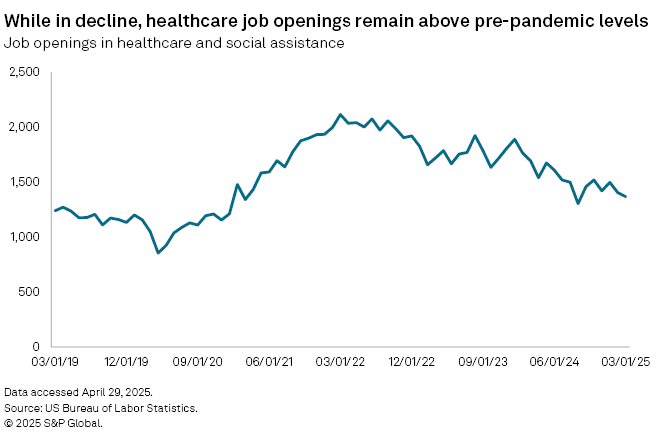

There were 1.37 million openings for healthcare and social assistance jobs in March, down from 1.69 million a year earlier and well below the peak of 2.12 million job openings in March 2022, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics.

"I suspect the cooldown in healthcare is tied to the fact that there have been so many jobs added in the sector over the past three years," Berger said. "It may well be that there is a natural slowing after such rapid growth."

Indeed's Stahle said this could be an early sign that uncertainty may be driving hiring decisions within healthcare.

"While the cooldown is spreading across most jobs in that industry, some social assistance job postings, like those in childcare, have pulled back even more dramatically in the last year or so after the expiration of federal grants and funding," Stahle said.