Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

5 Sep, 2022

By Ranina Sanglap and Rehan Ahmad

Banks in Asia-Pacific tread a fine line between higher margins and possibly stalling credit demand as interest rates rise across most of the region.

As record-low interest rates become a thing of the past across most of the globe, banks in Asia-Pacific expect improvements in their net interest margins. Australia's largest bank by assets, Commonwealth Bank of Australia, said in its full-year results that it expects margins to increase despite a decline in NIM to 1.90% from 2.08%. Likewise, the largest Indian bank, State Bank of India, reported higher NIM for the April-to-June quarter. State Bank of India Chairman Dinesh Kumar Khara said during an Aug. 6 earnings call that margins are expected to trend upward.

With rates likely to rise further, NIMs will increase, but they can also hurt borrowers' ability to pay and reduce credit demand. In the worst-case scenario, they can cause a buildup of bad loans and the banks would need to set aside more funds as impairment provisions.

"That's the balancing act that the banks have to go through," Andrew Gilder, Asia-Pacific banking and capital markets leader at EY, told S&P Market Intelligence in an interview. While the rise in interest rates will benefit lenders, they need to be conscious it will cause credit stress and increase impairment charges, Gilder said.

Inflation control

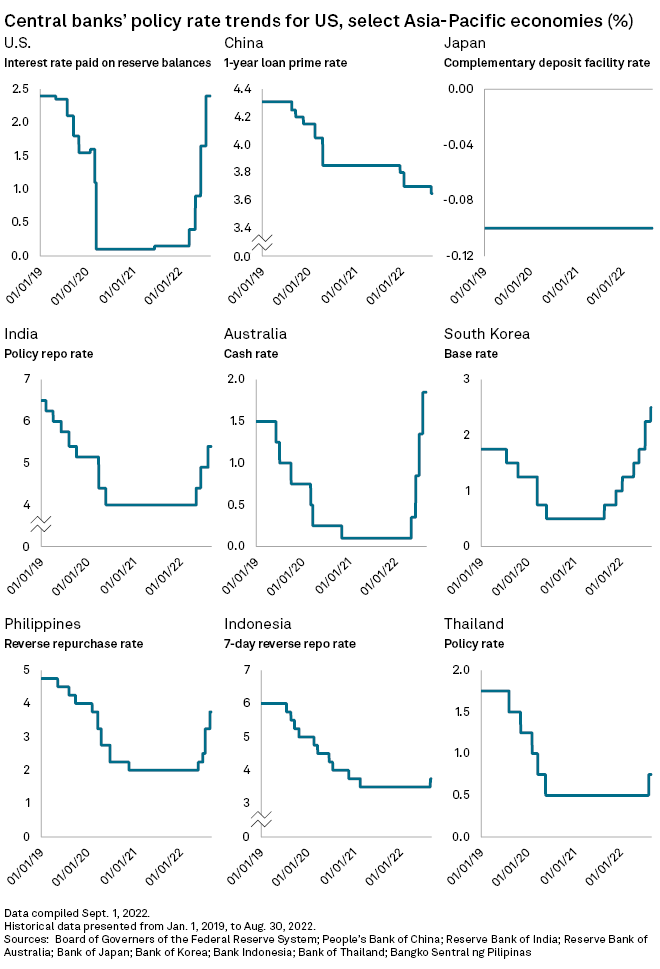

Central banks in India, Australia and Southeast Asia have raised rates from record lows since late 2021 as they shift focus to inflation control. The U.S. Federal Reserve has tightened monetary policy aggressively to counter decades-high inflation, triggering fears of capital outflows and weakness among currencies in Asia if central banks in the region can't keep pace.

"Interest rate rises are generally a benefit for banks because it helps them reprice their assets, and they can kind of lag the increase in the cost of their funding," Gilder said. Still, "as the payments go up, the cost of debt goes up for the consumer and for corporates as well. Their ability to make payments suffers, and therefore that causes an increase in nonperforming loans," Gilder added.

Banks across China, India and Australia raised their buffers against potential bad loans, according to their announcements during the recent results season.

"It's often important not just to look at rising rates, but also [at] the yield curve, which for the most part, has remained flat and thus has kept profitability low throughout this earnings season," said Ben Luk, a senior strategist at State Street Global Markets, referring to the commonly used proxy to assess how much banks can earn based on the difference in short- and long-term bond yields.

Hesitant customers

The other fallout of rising rates is the difficulty for banks to grow their lending books as customers become less willing to borrow; and many may delay big purchases such as homes and cars.

"Even if loan demand doesn't take a big hit, loan quality will worsen and the number of provisions will eventually go up," Luk said. "As economic conditions remain challenging, we believe the rise in net interest margins will not be able to offset the slowdown in aggregate credit over the medium term, especially if consumers are feeling the pain with muted wage growth and rising inflationary pressure."

Government debt will be a factor in several Asian countries. Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia are in a better position to withstand the pressures of higher rates on their economies because of their relatively lower public debt, said Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist for Asia-Pacific at Natixis Corporate and Investment Bank.

"However, for India, the increased cost of serving public debt should not be underestimated. This also means that Indian state-owned banks will need to swallow more government paper to lower the financing costs for the government, overall," Garcia-Herrero said, referring to the government's plan to borrow 14.31 trillion rupees in the year to March 2023 for public expenditure.

As long as economic growth doesn't collapse, higher rates will help banks. Emerging Asia economies have done well on economic growth so far, though frontier economies such as Pakistan and Laos are at risk, Garcia-Herrero said. "For Sri Lanka, banks are in technical default pending debt restructuring. We might have more cases coming like this."

Monetary policy differences

The central banks of Asia-Pacific two biggest economies are not tightening yet, since boosting gross domestic product growth remains their priority.

The Bank of Japan will likely maintain its yield curve control policy of targeting zero-yield on 10-year government bonds, with a tolerance of 0.25% on either side and a short-term yield of negative 0.1% until April, analysts said.

Rate increases in the U.S. could slow later this year. That "would ease the yen's fall and give the Bank of Japan leeway to keep the low interest rates," said Takahide Kiuchi, executive economist at Nomura Research Institute.

However, stable rates are a double-edged sword for Japanese banks, as they have been growing their overseas loans, Kiuchi said. For the fiscal first quarter that ended in June, the combined overseas loans at Japan's three megabanks rose 10% from the prior quarter to ¥114.6 trillion, nearly 40% of total loans.

The outlook for Chinese banks remains clouded by continuing rate cuts. The People's Bank of China on Aug. 22 cut its one-year loan prime rate by 5 basis points and five-year loan prime rate by 15 basis points. The one-year loan prime rate is a benchmark for most new and outstanding loans, while the five-year rate is typically a mortgage reference.

The rate cuts would provide short-term relief for borrowers but may not be enough to spur confidence in the economy, analysts said.

"It's this countercyclical way of regulators guiding banks to lend more to support the economy, but banks are still cautious," said May Yan, managing director and head of Greater China financial equity research at UBS. Bank reports indicate that property development loans at state-owned banks have grown moderately since the beginning of the year, but decreased at medium-sized joint stock banks, Yan added.