Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

21 Jul, 2022

By Cathal McElroy and Cheska Lozano

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez on July 12 announced a surprise tax on banks.

The Spanish government's plan to hit domestic lenders with a €3 billion windfall tax could scare away investors in the coming years as uncertainty persists over how long the measure will actually be in place.

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez announced the new tax July 12 as part of a package of measures to address the emerging cost of living crisis in the country as global inflation surges. The raid on banks aims to raise €1.5 billion in tax revenues from lenders' earnings in both 2022 and 2023.

The announcement had an immediate impact, prompting a sell-off in Spanish banks' shares. At their lowest, shares at Spain's six largest listed lenders fell by an average of more than 9% in the days after the announcement, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data. The shares have since recovered, and closed on July 20 at an average of more than 2% below their July 12 opening price.

Precise details about the nature of the tax and how it will be implemented remain unclear, with the prospect of the tax extending beyond the two years' earnings a concern for investors.

"The key risk here is that this transitory measure could be extended," Gonzalo Lopez, bank analyst at independent equity broker Redburn, said in an interview. "Investors are already anticipating that this could last more than two years, [now] that political risk is increasing in Spain. Sentiment has changed a lot."

The Spanish government is reportedly considering a levy of just below 5% on banks' net interest income, or NII, and commissions — the two main sources of Spanish lenders' revenues — as part of the package to raise €3 billion, sources told Reuters. The details of the government's plan are still being finalized and could change at the last minute, according to the sources. The plan is set to be discussed with the banks on July 22.

Spain's Ministry of Finance and Public Function said in an emailed statement that it is "working on the design of this temporary tax on banks." The details of the plan will be made public in due course.

"The government believes that this tax should not affect the confidence of investors in Spanish banks," the ministry said. "They are solvent and safe entities and that is not going to change due to the creation of this temporary tax."

The Association of Spanish Banks said it has yet to receive details regarding the tax. "Banks have not been consulted or informed, despite maintaining constant dialogue with government officials," the association said via email.

It remains unclear whether the tax will target Spanish banks' group income, which include profits from international markets, or just domestic income, sources said. Spain currently has double taxation treaties with more than 90 countries that prevent a company's foreign income from being taxed for a second time in Spain, according to consultancy firm PwC.

CaixaBank declined to comment.

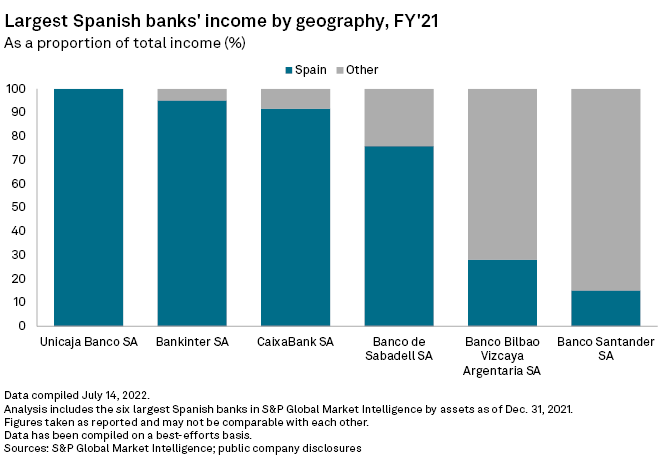

Banco Santander SA and Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA, Spain's two largest banks by total assets, would be less impacted due to their large exposure to international markets. Santander generated around 15% of its total income in 2021 from Spain, while BBVA received about 28% from its home market, Market Intelligence data shows.

Santander declined to comment. BBVA also declined to comment, but pointed to an interview given by Chairman Carlos Torres to El Correo in which he said that the best way for the government to increase tax receipts was to stimulate economic growth through bank lending, rather than targeting banks' income.

Unicaja Banco SA, the smallest of Spain's six largest lenders, is the only bank that does not have an international presence.

Political considerations

Spain's ruling Socialist Party and Podemos left-wing coalition came to power in January 2020 after elections a month earlier. Recent regional elections in Andalusia saw a surge in support for Spain's largest opposition party, the right-wing People's Party, while support for the Socialist Party fell to record lows.

The tax may be partly driven by a desire by the government to win back voters. "It's a measure directed at the left-wing electorate that abandoned the Socialist Party in the Andalusian elections," said Daniel Lacalle, chief economist at Madrid-based asset manager Tressis Gestion.

The scale of the initial sell-off in Spanish banks' stocks suggested that investors feared the government could eventually make the tax permanent, a note from Credit Suisse said. The discounts to share prices were close to double Credit Suisse's initial estimates of the potential tax impacts, it said.

The new tax running beyond its current two-year time frame is not unthinkable, said Redburn bank analyst Lopez. "We are going to have elections next year," Lopez said. "If there is a recession, maybe the government will extend the measure."

Investors had warmed to Spain's domestic-focused banks since January as the probability of interest rate hikes increased, promising a long-awaited boost to NII following a decade of record low rates and squeezed profit margins. Spanish banks are among the most sensitive in Europe to rising rates due to their income relying more heavily on lending and their loanbooks consisting of a relatively larger portion of variable-rate than fixed-rate loans compared to other markets, according to a June report by S&P Global Ratings.

Slim justification

Still, with eurozone interest rates only set to rise for the first time in a decade July 21, investors, analysts and the banks are struggling to understand the justification for the tax.

"One would expect a windfall tax where a firm is making excess profits," said Johann Scholtz, bank credit analyst at Dutch asset manager Actiam. "And it's very hard to argue that European banks or Spanish domestic banks in this instance are making excess profits."

The tax's impact on shareholder returns will make investors question the value of holding Spanish bank stocks, said Lacalle.

"It compresses the [price-to-earnings] multiples at which Spanish banks will trade," Lacalle said. "Any investor is going to think that when interest rates are negative, Spanish banks are going to lose money, and when interest rates are positive, Spanish banks are going to get some kind of [earnings] confiscation. Why would they pay 10x earnings for this?"

Spain's six-largest banks trade at between 4.9x price to the next-12-months' earnings per share for Santander and 9.2x price to the next-12-months' earnings per share at Bankinter SA, Market Intelligence data shows. The more domestic-focused Spanish banks trade at a higher multiple than Santander and BBVA, the data shows.

Whatever details about the tax emerge from the meeting between government and lenders July 22, the broad message sent by the tax will likely repel some investors observing the market from a distance, said Lopez. "An investor sitting in New York would say, 'If Spanish politicians or European politicians are doing these kinds of things, I don't want to be involved.'"