Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

22 Nov, 2022

Faced with hundreds of billions of pounds worth of debt to refinance and a massive energy bill package to fund, the U.K. government has backed away from plans to boost economic growth in a bid to appease financial markets.

Finance Minister Jeremy Hunt announced a £55 billion package of spending cuts and tax rises — some 2.5% of GDP — on Nov. 17 to plug the gaps in the public finances and calm government debt markets. The plan is a dramatic turnaround from the short-lived tax-cutting, high borrowing policy of former Prime Minister Liz Truss that sent bond yields and related borrowing costs soaring.

While the new plan has reversed a spike in yields that sent borrowing costs soaring, higher taxes will further squeeze households already suffering from high inflation and further curb economic growth. U.K. GDP shrank by 0.2% in the third quarter and while a post-COVID bounce earlier in the year will leave 2022 in growth territory overall, a recession is already underway, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility. S&P Global Market Intelligence forecasts a GDP contraction of 0.9% in 2023, followed by growth of just 0.7% in 2024.

"The balance of risks is tilting to the downside, reflecting the tougher tax regime and fears of significant housing market correction in line with rising mortgage borrowing rates and poorer households," said Raj Badiani, Europe economics director at S&P Global Market Intelligence, in a Nov. 17 note.

Economy in recession

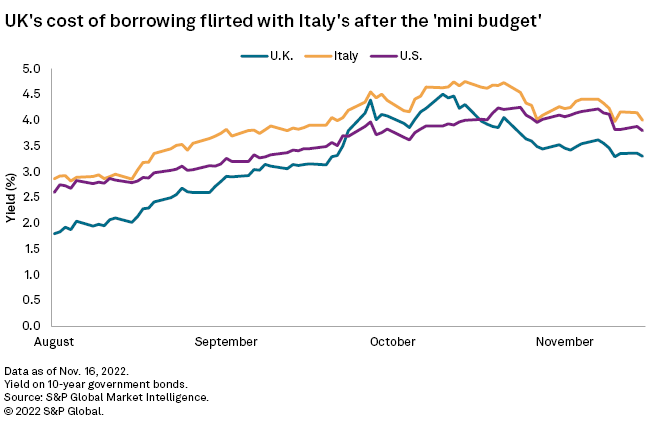

The newly announced plans have undone some of the damage to financial markets in the aftermath of Truss' poorly received September proposal for £45 billion in unfunded tax cuts. The former prime minister's plans pushed U.K. government borrowing costs towards the levels of Italy, a country with debt of over 150.2% of GDP as of the second quarter, compared to 101.9% in the U.K.

The yield on the benchmark 10-year U.K. government bond — or gilt — retreated to 3.2% as of Nov. 18, after climbing beyond 4.5% in October.

Still, the new plans are likely to hit U.K. consumers, whose spending accounts for about 61% of GDP.

Higher effective taxes compound the strain on households already reeling from a 41-year high consumer price inflation rate of 11.1%, high energy bills and rapidly rising mortgage costs. The erosion in living standards will reduce household income by 7% over two years, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Alongside the contraction in GDP, consumer confidence is low with real household spending falling 0.5% in the third quarter, according to government data. Meanwhile, business investment — already hamstrung by the uncertainty of the Brexit years and COVID-19 —was also down 0.5% during the period. In GDP terms, the U.K. is the only G-7 country with a smaller economy than before the start of the pandemic in January 2020.

"What investors want is a believable plan," said James Sproule, chief economist U.K. at Handelsbanken. "Our debt levels are slightly lower than the G-7 average. Remember that debt investors are not interested in growth, they just want their money back with interest."

Tight labor markets weaken

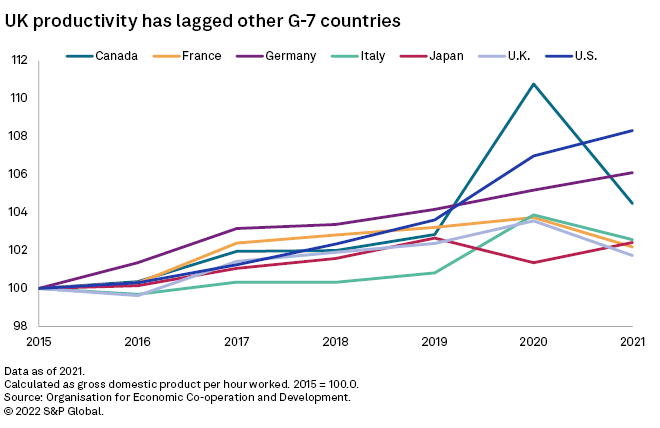

Global forces are at play with much of the world facing high food and energy costs. However, the U.K. economy has other structural weaknesses, including the lowest productivity rate among the leading industrial nations comprising the G-7, and now a squeeze on its labor force.

As in the U.S., the U.K. labor market is tight, with an unemployment rate of just 3.6%, and that tightness is being exacerbated by a rise in economic inactivity, which refers to people who are either not looking for or are unavailable for work. That rise is being driven by older workers — though in recent months compounded by younger people — with long-term sickness linked to the effects of COVID-19 and a strained health service.

Productivity has also been a long-term lag on the U.K. economy since the great financial crisis in 2008-2009 with higher regulation impacting financial services, while political uncertainty in the years since the country's decision to withdraw from the European Union in 2016 has weighed on business investment.

Economies grow on either increased labor producing more or increased productivity of the existing workforce. The weakness of both of these measures means the potential for GDP growth is flat.

"Productivity will continue to languish as the general economic outlook is poor — so why will big firms invest — while smaller firms are likely to struggle given the broader economic backdrop," Sproule said.

This has implications for future tax returns for a government already reliant on borrowing to plug the gaps in its budget deficit, forcing the government to bend to the market's will.

Dependence on investors

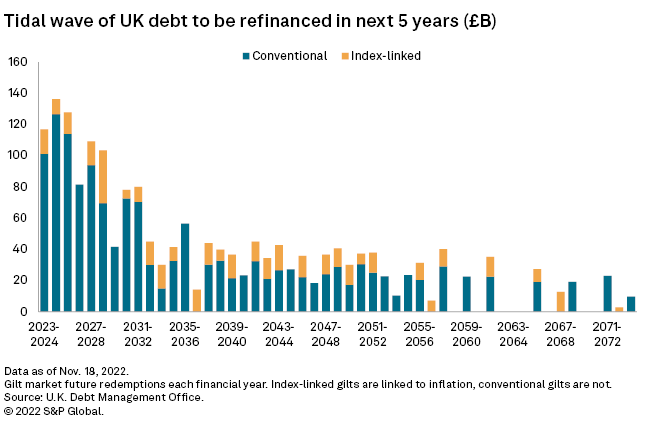

The rise in government bond yields reflected a market adjusting to the U.K.'s growing reliance on international investors. While the government's latest actions reduce the value of gilts coming onto the market between now and March 2023 by £24.4 billion, the 2023-2024 total is "eye-watering," according to James Lynch, fixed income investment manager at Aegon Asset Management.

The expensive energy package — £55 billion in subsidies for households and businesses for just the coming winter alone — and the outlook for sustained growth in debt levels moved S&P Global Ratings to revise down its outlook for the U.K. rating to negative in September.

"Investor confidence in the U.K. is particularly crucial at this juncture because any additional debt issuance the U.K. Treasury is planning comes on top of the approximately 30% of the U.K.'s total outstanding debt that will have to be refinanced over the next five years," said Eiko Sievert, director of Sovereign Ratings at Scope Ratings.

Some £305.1 billion of U.K. debt will land in the market in the 2023-2024 fiscal year, £113.8 billion more than had been predicted in March 2022 as the government funds its package to reduce energy bills for households and businesses, without which, the ONS estimates inflation would have been well in excess of 13%. Of that larger total, £117 billion is redeeming existing debt which will be refinanced at higher rates, placing more strain on public finances.

"I would not be surprised that yet again in 2023 we will be talking about the market's ability to absorb a large amount of gilt issuance," said Aegon Asset Management's Lynch.

The Bank of England is also testing investor appetite for U.K. debt by beginning to unwind its £957 billion balance sheet, built up to defend the U.K. economy during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

That sell-off will likely drive bond prices down and yields higher. BNP Paribas forecasts yields on 10-year gilts will return to 4% in the coming quarters.

"While the reduction in this year's Debt Management Office remit was larger than expected, the outlook for supply, especially when Bank of England's quantitative tightening and temporary purchase sales are taken into account and the size of the gilt funding outlook over coming years, keeps us bearish," said Paul Hollingsworth, chief European economist at BNP Paribas.