Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

16 Aug, 2021

By Brian Scheid

After roughly four months of flattening, the Treasury yield curve is steepening again in response to rising inflation and the Federal Reserve's seemingly imminent plans to tighten its ultra-loose monetary policy.

Analysts say the steepening curve — a linear comparison of interest rates for bonds with different maturities — is the government bond market reflecting growing expectations for a robust rebound and a healthy, post-pandemic economy as longer-maturity yields rise faster than shorter-term yields. But with the recovery still on an unclear and perilous path forward amid growing COVID-19 cases and unemployment numbers still well above pre-pandemic levels, spreads could begin to narrow again.

"The curve would flatten again if there were signs that growth was slowing, inflation was falling, and/or the Fed was moving quickly to tighten policy to cool off the economy," said Kathy Jones, managing director and chief fixed-income strategist for the Schwab Center for Financial Research.

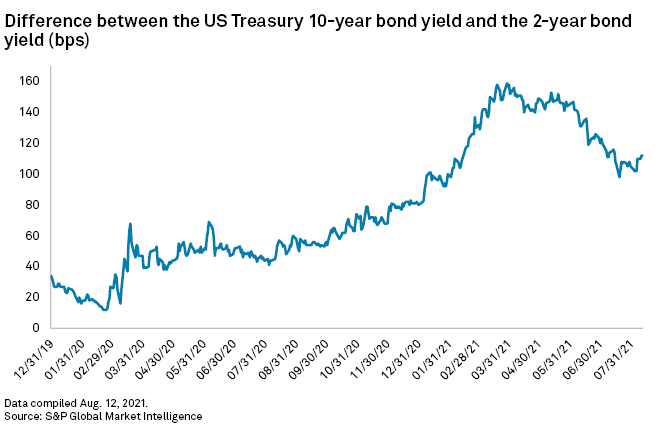

The spread between the benchmark U.S. Treasury 10-year bond yield and the two-year yield, a key indicator of the yield curve's shape, climbed to nearly 160 basis points at the end of March. The widening spread was propelled by a Democrat-controlled Congress pushing through more fiscal stimulus and climbing vaccination rates.

Bond yields move inversely to bond prices. Falling yields indicate an increased investor demand for the relative safety of bonds over riskier assets such as equities.

Stagflation risk

By early April, the yield curve began to flatten on slowing vaccination rates, stagnant unemployment, a global supply bottleneck, and fears of the impact of COVID-19 variants.

By mid-July, the spread was below 100 basis points.

"If the curve doesn't steepen in the weeks and months ahead, that will be a problem for markets," said Tom Essaye, founder and president of Sevens Report Research, in an Aug. 12 note.

A flatter curve will signal that the bond market forecasts a loss of economic momentum and increases the likelihood of an era of stagflation, where inflation and unemployment remain high and economic growth remains slow, Essaye said.

But some bond strategists believe that the mid-July low may have been a bottom and the yield curve may be facing months of steepening.

Gennadiy Goldberg, senior U.S. rates strategist at TD Securities, said the curve will likely continue to steepen as the market prices in ongoing, rising inflation and a Fed gradually moving towards a rate hike. Inflation can diminish the future value of a bond. The risk of inflation rising also tends to push yields up as investors seek compensation for the potential loss of purchasing power.

"After the summer, we think a combination of stronger economic data, [quantitative easing] tapering discussions by the Fed, and additional fiscal policy should help drive rates higher and the curve steeper," Goldberg said.

The spread between the 10-year and 2-year yields has risen 15 basis points as of Aug. 12 since hitting its mid-July low. The spread between the 30-year and 5-year yields, another measure of the steepness of the yield curve, rose 9 basis points over the same stretch.

Since mid-July, longer-dated bond yields have trended upwards as a growing number of Fed officials have signaled that a taper of its monthly purchases of $120 billion in Treasurys and mortgage-backed securities could begin as soon as this fall. Fed President Jerome Powell may outline the central bank's tapering plans in a speech later this month at the central bank's annual economic policy symposium.

Taper pace

The steepening curve shows that the bond market believes that the central bank's monthly bond purchases will be tapered at an acceptable pace to support the economic recovery, said Brian Luke, global head of fixed-income indices at S&P Dow Jones Indices.

Luke said this will likely prevent a faltering economy and a significant move from investors from riskier assets, like stocks, to safer assets like bonds. Instead, the Fed will gradually slow its purchases and yields will likely climb higher, Luke said.

Since July 19, the 10-year yield jumped 17 basis points to settle at 1.36% on August 12, its highest close in nearly a month. The yield fell to 1.29% on Aug. 13 following the release of early August data for the University of Michigan's gauge of consumer sentiment, which showed the measure dropped to its lowest level since December 2011.

Even at its high on Aug. 12, the benchmark yield was 38 basis points below its prior high in March, after bond yields collapsed while equity indexes continued to rally to new, all-time highs.

"The stock market remained confident in the recovery while I think bond yields went through a bit of a head fake from June to July," Luke said.

The shape of the yield curve depends almost entirely on the direction of the 10-year and other longer-dated yields since the 2-year and other yields with shorter maturities are largely anchored by the Fed's policy of keeping the federal funds rate at near 0%.

The 10-year yield declined from March as the bond market "pared its expectations" for economic growth and the Fed's target for raising rates,