Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY — Jun 07, 2022

The pace of global economic growth remained among the weakest seen so far during the pandemic recovery period in May, according to the latest PMI data compiled for JPMorgan by S&P Global. The rate of growth inched higher, however, as the severe downturns that have afflicted the economies of mainland China and Russia showed signs of moderating. At the same time, looser COVID-19 restrictions helped drive growth rebounds around the world.

Soaring prices nonetheless took some of the heat out of economic growth in many economies, notably in the US and Europe, with companies also continuing to report business activity levels to have been constrained by shortages of both materials and labour.

The outlook is mixed, as service sector recoveries look likely to lose some further momentum in coming months as the initial boost from pent-up demand fades, while inflation remains elevated and monetary policy is expected to further tighten. On the other hand, demand growth could revive - and global supply chain issues diminish - as China starts to reopen its economy from Omicron-related restrictions.

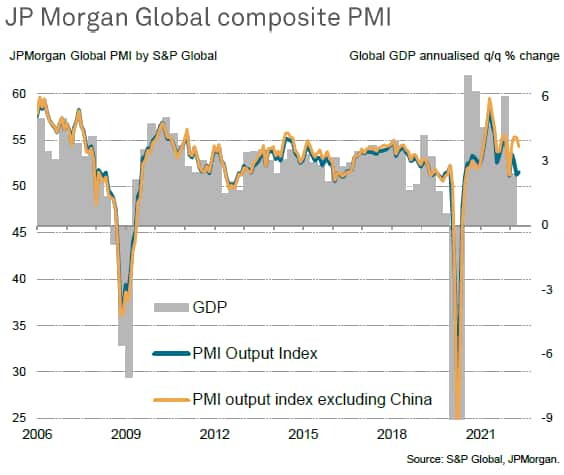

The JPMorgan Global Composite Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™), compiled by S&P Global, registered 51.5 in May, up slightly from 51.2 in April but still indicating the third-weakest global expansion seen since July 2020. So far in the second quarter, the global PMI has been running at a level broadly indicative of worldwide GDP rising at a sluggish annualised rate of just 2.2%.

However, this subdued performance can largely be attributed to a steep downturn in mainland China amid lockdown restrictions designed to curb the spread of COVID-19. Note that, if China is excluded, the global PMI registered 54.3, down from 55.3 in April but indicative of a more impressive annualised GDP growth rate of approaching 3.5%.

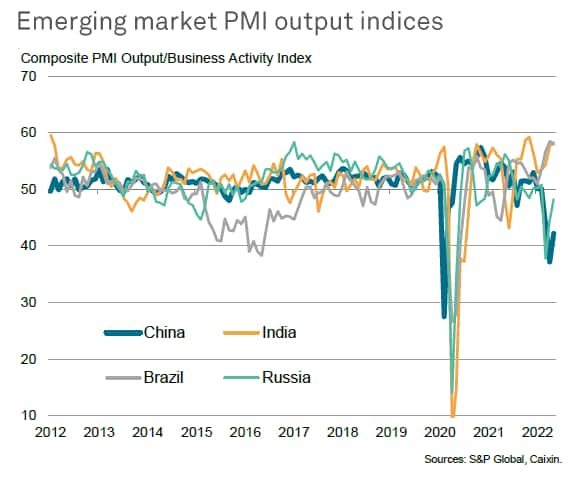

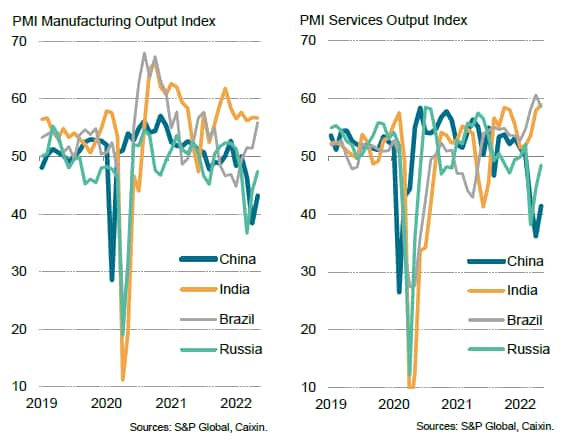

At 42.2, the Caixin composite PMI for mainland China, compiled by S&P Global, rose from 37.2 in April thanks to easing downturns in both manufacturing and services, but remained in deep contraction territory. The survey has now signalled the most severe three-month period of contraction in the history of the China PMI, which extends back to 2004.

Meanwhile, with sanctions continuing to be applied amid the ongoing war in Ukraine, Russia also remained in a downturn for a third month running, suffering its steepest three-month period of contraction since the global financial crisis. This is with the exception of the initial pandemic collapse, albeit with the rate of decline moderating sharpy in May. Russia's composite PMI rose from 44.4 in April to 48.2 in May, despite its export index remaining in especially steep negative territory in a reflection of war-related sanctions.

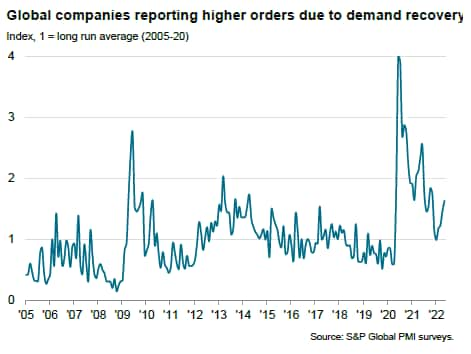

In contrast, especially strong expansions were recorded in other emerging markets such as India and Brazil, where growth rates were among the highest seen over the past decade supported by robust output growth of both manufacturing and services as COVID-19 restrictions were eased. India's composite PMI hit a six-month high of 58.3 as its service sector surged at a rate not seen for 11 years. In Brazil, the composite PMI fell from 58.5 to 58.0 but remained the second-highest recorded since 2007, likewise led by a rebounding services economy.

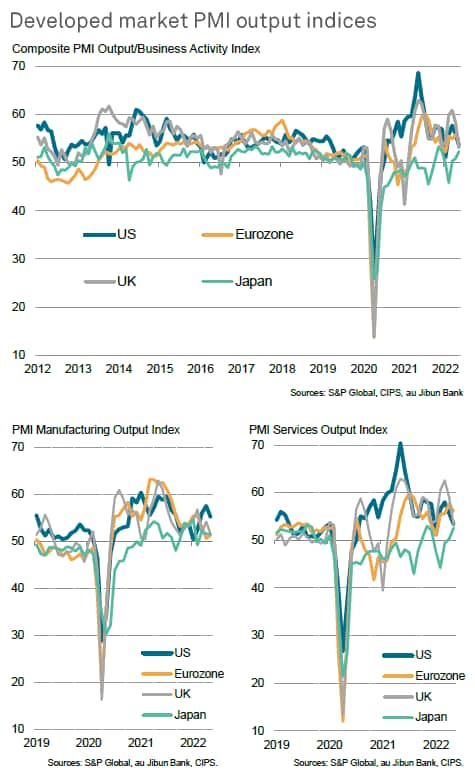

Similarly, robust growth was seen on average in the eurozone, and most notably in France, due principally to improved service sector performances following the relaxation of pandemic restrictions in recent months. The Eurozone, with a PMI reading of 54.8 consequently outperformed the US and UK, despite the index cooling from 55.8 in April due to the service sector rebound losing some momentum. Manufacturing output remained subdued across the single currency area due to shortages and soaring costs.

Growth rates meanwhile eased in the US and UK, linked primarily to more severe losses of momentum in the service sectors compared to the eurozone, as well as slower manufacturing expansions amid ongoing supply-side constraints, both in terms of materials and labour. The US composite PMI fell from 56.0 to a four-month low of 53.6, while the equivalent index for the UK slumped from 58.2 to a 15-month low of 53.1.

Bucking the major developed world economy slowdown trend was Japan, where the au Jibun Bank composite PMI rose from 51.1 to 52.3, its highest since December, thanks in particular to a resurgent service sector.

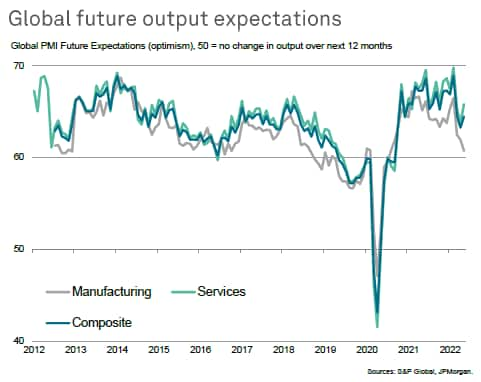

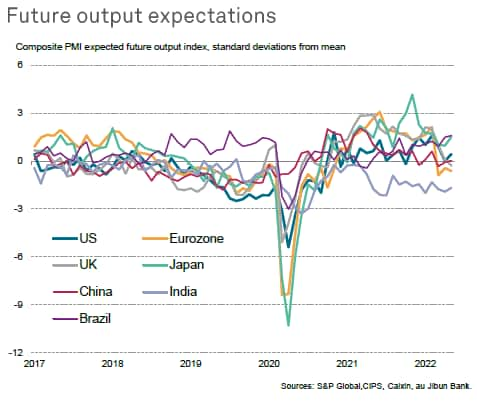

The May PMI surveys meanwhile saw global business expectations about growth in the next 12 months lift higher for the first time in three months, albeit with the improvement limited to services and remaining overall at one of the lowest levels seen over the past two years.

Future expectations remain especially weak by historical standards in India and the eurozone, and have now dipped below the long-run average in the UK. Sentiment in the US and China has picked up but merely remains close to long-run averages, leaving Brazil and Japan as the world's largest economies with the highest degree of future business sentiment once long run trends are taken into account.

This beckons the question as to whether growth will show signs of improvement in the second half of 2022. While services business confidence has lifted higher, the goods producing sector has yet to show signs of a turnaround as the global economy eagerly awaits the easing of disruptions from the Omicron virus' impact on China and, eventually, with the Ukraine war.

The differing world growth rates in part reflect timings in relation to the easing of COVID-19 containment measures following the Omicron wave. The UK and US had opened up earlier from their Omicron waves and have since reported this rebound losing some impetus. In contrast, later waves in the eurozone and Japan mean Omicron-related restrictions had been relaxed later than the US and hence are now seeing more growth momentum for services. The suggestion is that eurozone and Japanese growth, as well as the growth spurts seen in India and Brazil, could likewise start to moderate as this boost from pent-up demand wanes. However, at the same time, growth could soon revive - potentially strongly in the near term - in China as restrictions are relaxed. Given the sensitivity of global growth to China's impact, this could mean some improvements in the months ahead, though the supply effects should also be considered.

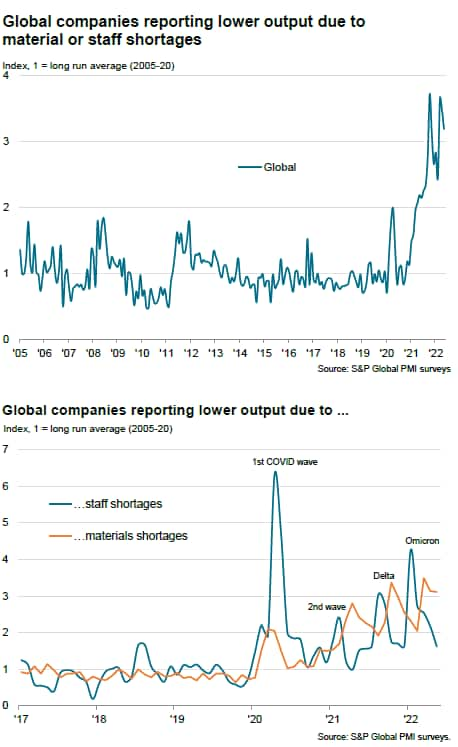

The survey data also point to global supply chains continuing to be hit hard by the twin effects of the war in Ukraine and China's latest lockdowns, which should ease to some degree once China's restrictions are loosened. May saw the proportion of companies worldwide reporting that output had fallen due to material supply shortages running close to an all-time high still, reflecting the accumulating impact of bottlenecks in recent months.

Perhaps more encouraging is the labour supply picture. Although many companies continue to report labour availability problems and staffing shortages linked to illness, most notably in the US, the proportion of companies reporting output to have fallen due to staff shortages has fallen sharply since the Omicron peak at the start of the year.

The supply chain and labour supply constraints emanating from the pandemic could therefore play a reduced role in curbing economy recovery in coming months, while at the same time taking some of the heat out of inflation on a global scale. That said, it is also important to consider that while the easing of virus disruptions in China may have a primary effect of boosting demand and supply conditions, thereby supporting output, the release of pent-up demand could feed into higher price pressures in the short-term and induce further monetary policy and safety stock buying tendencies, altogether a delicate equation to weigh.

Sign up to receive updated commentary in your inbox here.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, S&P Global Market Intelligence

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@spglobal.com

© 2022, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

Location