Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Research — 22 Nov, 2023

By Xylex Mangulabnan and Harry Terris

Sentiment on bank stocks remains stuck in a rut even after a couple of strong weeks in November that brought a measure of relief to the sector.

Stocks, and especially bank stocks, have been trading in tandem with bonds lately. Bonds rallied in late October and most of November so far, as the yield on 10-year Treasuries tumbled 54 basis points from a recent peak to 4.44% at Nov. 17.

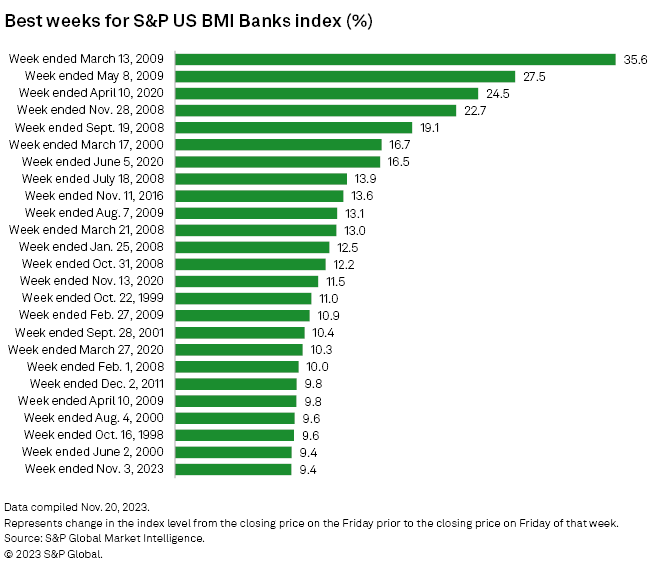

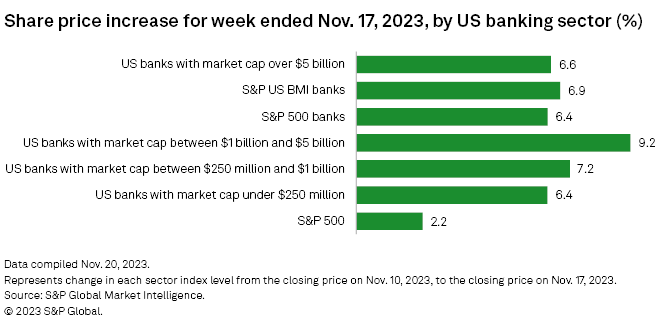

The S&P US BMI Banks index, meanwhile, scored one of its 25 best weeks since 1990, posting a 9.4% gain for the week ending Nov. 3. It added another 6.9% in the week ended Nov. 17. Still, those moves only modestly changed the overall picture after a swoon in March following the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. The banks index was down 7.3% for the year at Nov. 17, compared with a gain of 17.6% for the S&P 500.

A number of analysts said sentiment on banks will not shift until there's more clarity around rising credit costs.

"The reason why portfolio managers are not taking advantage of these valuations, bank stock valuations relative to the broad market, is nobody wants to own a lot of bank stocks — whether it's large cap or mid-cap — ahead of a credit event, ahead of a recession," UBS analyst Erika Najarian said at a conference on Nov. 16.

If confidence around the credit trajectory is the key to a fuller recovery in bank stocks, the analyst offered a hopeful note reflecting the growth of nonbank lending in various commercial and consumer markets over the last decade or so.

"We've had, with the exception of credit card, a pretty significant risk transfer since the global financial crisis," Najarian said. "If we ever get this recession, the upcoming credit cycle, I actually think the peaks will be lower than even other mild recessions."

Movers

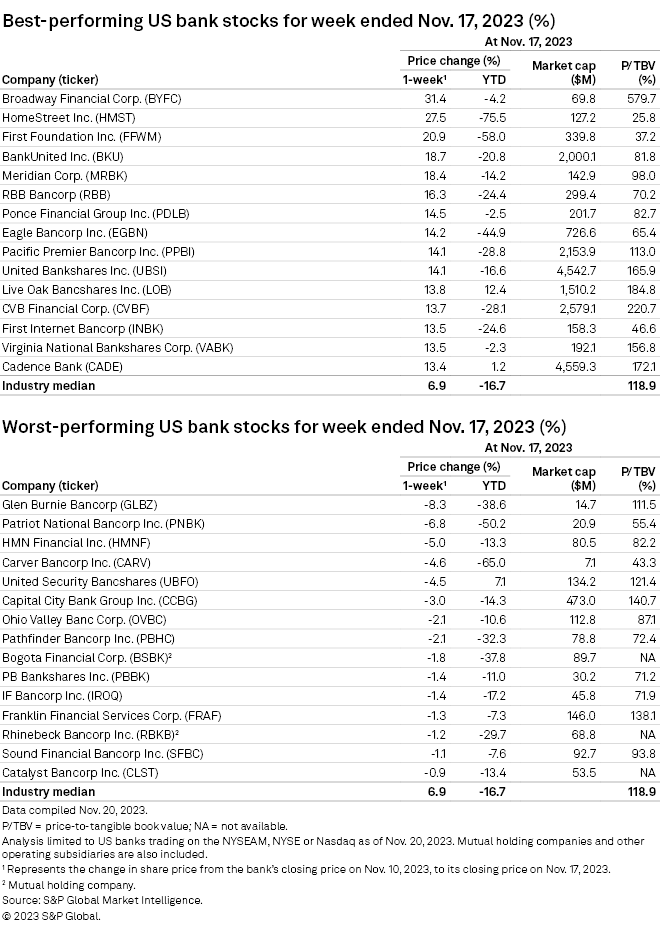

The rallies in November did deliver particularly strong rebounds for some banks that have been among the cheapest in the sector, including HomeStreet Inc., First Foundation Inc. and Eagle Bancorp Inc.

While those banks posted gains of 14.2%-27.5% during the week that ended Nov. 17, they still remained down 44.9%-75.5% for the year.

Net interest margins (NIMs) at HomeStreet and First Foundation have been hammered in the current cycle. NIMs fell to 1.78% in the third quarter from 3.39% in the fourth quarter of 2021 at HomeStreet, and to 1.65% from 3.18% at First Foundation, according to data from S&P Global Market Intelligence.

The rates link

A decline in interest rates relieves pressure on funding costs for banks, and also helps to unwind damage to the fair value of their holdings of bonds and loans that were added to balance sheets when rates were even lower.

With the Federal Reserve at or near the end of its rate hikes for the cycle, many banks have forecast near-term troughs in NIMs.

"We do think NIMs bottom" by the first quarter of 2024, Piper Sandler analyst Stephen Scouten said in a note on southern banks on Nov. 13. Still, "we expect that investors will need to be able to ring-fence the credit cycle before the group can move consistently higher."

The rate relationship is not necessarily straightforward. Among big banks, Bank of America Corp. has disclosed among the largest hits to the fair value of its balance sheet, while also giving guidance that fewer rate cuts than markets anticipated for next year would help its net interest income.

Some analysts argue that higher interest rates are structurally better for banks, at least compared to the very low interest rates that prevailed for most of the 2010s.

"There's actually nothing more disruptive to the banking industry than a zero interest rate policy for a long time," Najarian with UBS said.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.