Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

BLOG — Nov 09, 2021

By Todd C. Lee

A common assertion in the business and financial press analyzing the Chinese property developer Evergrande's liquidity crunch is that the real problem Evergrande has exposed is China's flawed and unsustainable economic development model that depends on the property sector as a growth driver. This assessment is erroneous, as it mistakenly identifies causality between China's economic and property sector developments. China's property sector is not a growth driver of the Chinese economy, but a growth passenger. The sector has simply ridden the wave of China's remarkable economic rise, which was the result of structural economic reforms that lifted productivity growth. The unique characteristics of the Chinese economy have further fueled the Chinese property sector's expansion and caused it to become excessively large.

Why property sector is China's "growth passenger", not "growth driver"

The fact that China's property sector rode the coattails of the rapidly growing economy rather than driving economic growth can be explained by the Balassa-Samuelson effect, a theory developed by economists Bela Balassa and Paul Samuelson to explain why the price levels in advanced economies are higher than in developing economies. The Balassa-Samuelson effect postulates that advanced economies' labor productivity is higher than that of developing economies in sectors engaged in international trade, while the labor productivity differential in the non-tradeables sector between advanced and developing economies is marginal (For example, labor productivity of the US aircraft manufacturing is much higher than Sri Lanka's labor productivity in textiles, but the productivities of barbers in the US and Sri Lanka are roughly the same). Advanced economies' higher productivity in the tradeables sector leads to higher wages and higher production costs for non-tradeables - and hence higher non-tradeables prices. This explains why non-tradeables such as haircuts, restaurant dining, and housing are much more expensive in the US than in Sri Lanka. The rapid ascent of China's housing prices is thus driven by the Chinese economy's persistently high productivity growth unleashed by the reform and opening-up policy launched in 1978. Sustained urbanization also supported the housing market's expansion. In 1998, when China's welfare housing system was dismantled, 33.4% of the population lived in urban areas, and by 2020, 63.9% of the population resided in cities.

China's financial system and fiscal arrangement led to property sector's excess expansion

Besides these fundamental factors supporting China's housing sector development, the country's underdeveloped financial market has further boosted the housing market's rapid rise. That is, as the Chinese financial markets offer few viable investment options to Chinese households, housing has become an investment vehicle of choice. Housing accounts for around 60% of Chinese urban households' assets, compared with 30% of US households' assets held in housing. China's fiscal system also created incentives for local governments to favor housing market development. The supply of land in China is controlled by local governments and selling land-use rights to property developers is the sole direct revenue source for local authorities. More than 40% of local government revenues are derived from land sales. Local governments' heavy dependence on land sales creates incentives for them to focus their economic development policies on the real estate market. Moreover, the heavy fiscal dependence also incentivizes local governments to restrict land supply to ensure high land sale prices, and thus maximize land sale proceeds. This land scarcity further exerts inflationary pressure on China's housing prices.

Chinese property sector expansion is increasingly hollow

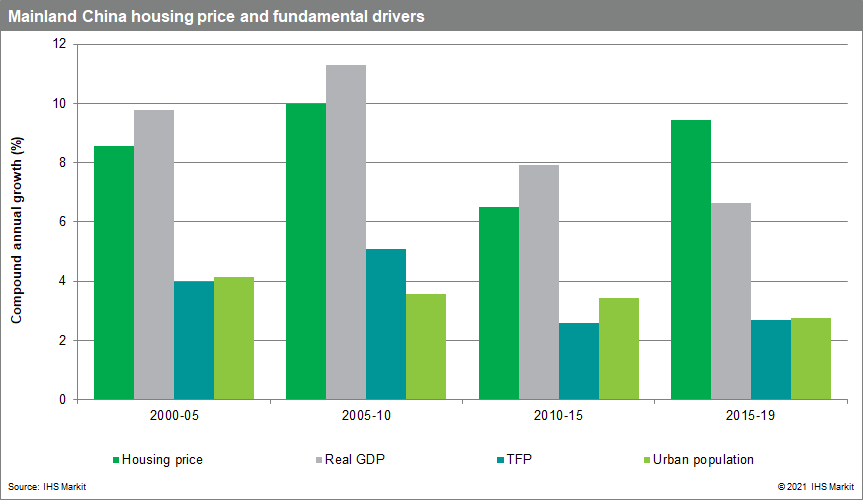

From 2000 to 2015, China's housing market expansion was largely in line with fundamentals, as housing prices rose at 8.3% in compound annual growth rate (CAGR), while real GDP grew by 9.7% CAGR. Growth of total factor productivity and urban population during this period was also solid, at 3.9% and 3.7% CAGR respectively. Since 2015, however, the fundamental underpinnings of housing demand have deteriorated - but housing prices continued to soar. From 2015 to 2019, the national average housing price rose by 9.4% CAGR, while the CAGR of real GDP, total factor productivity, and the urban population fell to 6.6%, 2.7%, and 2.8% respectively. Housing sector expansion began to deviate from fundamentals after the 2008-09 global financial crisis. To stave off the economic downturn caused by the crisis, Beijing unleashed massive fiscal and monetary stimuli. Real GDP growth was propped up by loose credit-fuelled investment expansion, rather than driven by solid productivity growth. In fact, total factor productivity growth began to decline after the global financial crisis, as boosts from earlier economic reforms waned and new reforms stalled.

Real risks of the Chinese property sector

The real risk that the Evergrande crisis has exposed, therefore, is that the Chinese property sector - owing to the increasingly hollow expansion - could collapse under its own weight and exact severe damage on the economy, given the sector's immense size and reach.

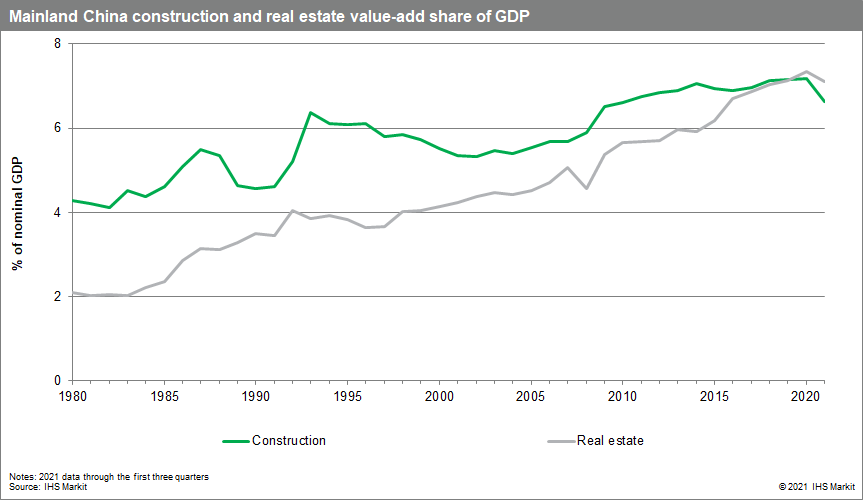

Since China dismantled its welfare housing system in the late 1990s, housing market-related sectors have significantly expanded their footprint in the economy. Value-added generated by the construction and real estate sectors accounted for a combined 9.9% of GDP in 1998, and by 2020 the two sectors accounted for 14.5% of GDP. Housing also accounts for an increasingly larger share of China's investment spending. In 1999, residential real estate investment accounted for 8.8% of China's total fixed asset investment. By 2020, housing investment's share of fixed asset investment rose to 19.8%. The property sector is also a major employer of the Chinese economy. The construction and real estate sectors together employed nearly 16% of urban workers, up from 7%-plus in the late-1990s. Besides its massive footprint in the real economy, the property sector has also grown to carry enormous weight in China's financial system. Property loans accounted for 28.9% of bank loans at the end of 2020.

The central government's latest property market tightening policies have suspended the sector's excess growth and lowered the risk of a housing market crash. However, unlike previous policy cycles of property sector tightening, China's economic growth is no longer brisk and robust, and able to quickly absorb the sector's past bloated expansion. If the Chinese government continues to put off economic reforms, China's true growth driver, productivity growth will continue to slow and economic growth will further grind down. In that scenario, the weight of the property sector - the outsized growth passenger - could become unbearable.

Posted 09 November 2021 by Todd C. Lee, Chief China Economist, S&P Global Market Intelligence