Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Research — 18 Oct, 2022

Introduction

The glimmer of recovery that rejuvenated the market in early summer got all but snuffed out as autumn ominously rolled around. By the time the seasons had changed, the earlier concerns about a possible economic recession had solidified in tangible steps against a downturn: cutting costs, slowing expansion and laying off employees — all things that go directly against M&A.

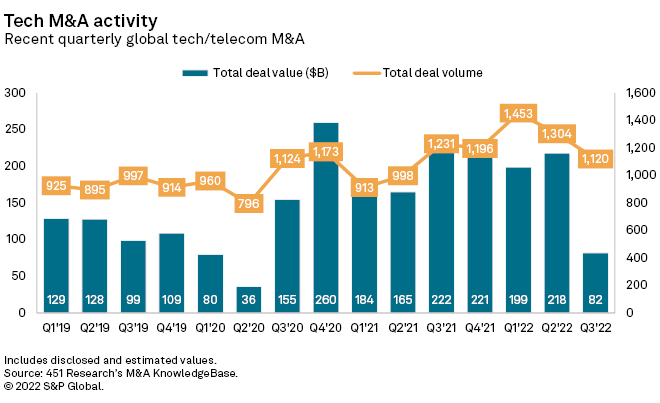

Tech acquirers got the message in the third quarter. They pared back purchases, dropping spending on deals around the world to only about half the amount they had doled out in any quarter since emerging from the sharp contraction due to the COVID-19 outbreak, according to 451 Research's M&A KnowledgeBase. The value of third-quarter deals did not even make it back to pre-pandemic levels.

* Spending on tech transactions announced in the June-September period plunged to just $82 billion, the M&A KnowledgeBase shows. That compares with a quarterly average of slightly more than $200 billion since mid-2020 when tech led the broader economy out of the pandemic-induced recession.

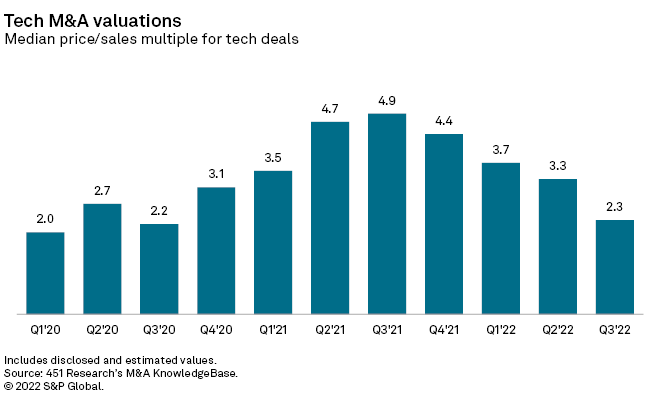

* Recent deals have been sharply discounted, with the prevailing price-to-sales multiple in the third quarter dropping to pre-COVID-19 levels. Our data indicates that tech M&A valuations, which peaked during last summer's bull market at 5x sales, have plunged uninterruptedly to just 2x now.

Emerging from the pandemic, tech dealmakers took advantage of a once-in-a-generation opportunity as the industry led the way out of the sharpest economic contraction in U.S. history. Spending on tech acquisitions shattered records. Since mid-2020, for instance, there were eight individual months in the M&A KnowledgeBase where deal value topped the aggregate spending for all three months of the just-completed quarter.

But the days of hand-over-fist spending are over. As the autumnal activity in the just-completed third quarter indicates, tech acquirers are figuring out how to do deals in a downturn.

From handshakes to wave-offs

Since the midyear point, 2022 has not looked anything like 2021, which featured historically confident acquirers paying record prices and spending record amounts. Deals that would have breezed through approvals from boards of directors or investment committees last year are now getting tabled. Negotiations that would have previously led to handshakes and on-the-dotted-line signatures instead get dismissed with a terse: "Now's not the time."

As an indication of the red-hot to ice-cold shift in the tech M&A market, consider two of the largest transactions from the just-closed quarter. The blockbusters would have fit in 2021's high-flying M&A market but look out of step now.

* Strategic: In the third quarter's biggest single acquisition, Adobe Inc. said it will pay $20 billion for Figma Inc. The deal roughly equals the combined spending of the third quarter's next three largest transactions in the M&A KnowledgeBase. Wall Street was not only concerned about the size of the deal. Many investors sold their shares in the enterprise software vendor because it is paying the richest-ever valuation in a significant software-as-a-service, or SaaS, purchase just as its own growth drops to half of what it had been.

* Financial: Despite having snapped up more tech providers than any other private equity firm in the M&A KnowledgeBase, Vista Equity Partners Management LLC took an unusually light-handed approach in its latest buyout effort. Vista put forward a $4.2 billion offer for cybersecurity training specialist KnowBe4 Inc. but did not fully make it legally binding. Investors did not know what to make of the bid, which is technically a non-deal deal. Shares of KnowBe4 initially spiked to nearly the level of Vista's mid-September offer but dropped steadily to close out the quarter at a mid-teens discount to the bid.

More broadly, buyers — and, indeed, much of the rest of the economy — basically gave up on the idea of a "soft landing" for the economy from the decades-high inflation and started bracing for a much more jarring impact. But how much more jarring?

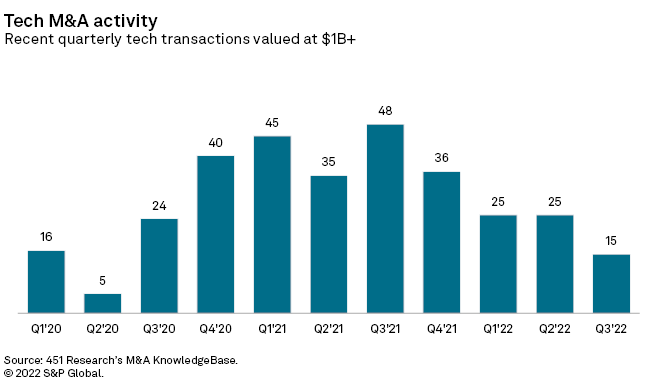

Overwhelmingly, institutional investors surveyed by S&P Global's Investment Manager Index predicted that the U.S. would tip into a mild recession. Still, with that amount of bearishness about the overall economy, it is hard to be bullish about doing deals, particularly anything with a lot of zeros in the price. The M&A KnowledgeBase shows that over the past three months, acquirers announced just 15 transactions valued in the billions of dollars — only about one-third of the quarterly average from last year.

Brought low — and bought low

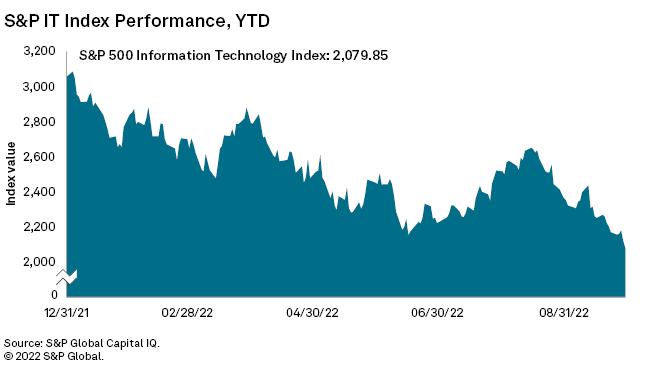

Persistent worries about a recession, which have hit the tech industry harder than most, created discounts that have not been available during the two-year rebound following the COVID-19 outbreak. (On Wall Street, most of the major indexes closed out the third quarter on pace for the deepest year-to-date losses since the Great Financial Crisis more than a decade ago, according to S&P Global Capital IQ.) In M&A, once highly valued companies have been brought low — and bought low this summer.

* With its shares having lost 90% of their value over the past half-decade, Micro Focus International PLC agreed to consolidate its shrinking business with Open Text Corporation at a valuation of just 2x revenue.

* ironSource Ltd., which began its post-special purpose acquisition company, or SPAC, life valued well north of $10 billion, agreed to sell to Unity Software Inc. for just $4.4 billion in stock. Since it announced the purchase, Unity's shares have dropped 20%.

* Amid declining sales and red numbers, iRobot Corp. sold itself to Amazon.com Inc. for just 1x trailing sales. That is the lowest valuation Amazon has ever paid in a significant transaction in the M&A KnowledgeBase.

If anything, the downward pressure on valuations intensified on deals that came below the top end of the tech M&A market. In particular, two types of smaller transactions, which are becoming increasingly common as the economy tanks, are compressing multiples: "soft landings" for venture capital-backed startups and divestitures by major tech vendors.

Both deals are variations of capitulation, essentially giving up on a business because of dwindling prospects. (Those strategic decisions — whether by investors or executives — are part of the "painful" process that U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell warned about in mid-September, as he continued the Fed's unprecedently steep interest rate hikes to bring down decades-high inflation.) With both capital and growth becoming harder to find in the tech industry, expect even more of those low-multiple transactions.

As early examples of this trend, the previous quarter saw Uplogix Inc. — a network management startup that had raised close to $50 million in funding — sell in September for just $8 million, or 1x trailing sales. Similarly, serial acquirer Singapore Telecommunications Ltd. in July unwound its decade-old purchase of advertising software provider Amobee Inc. at a significant discount to the original purchase price and, especially, the valuation.

Overall, according to our data, tech M&A multiples have been more than cut in half over the past year. Valuations have declined every quarter since last summer, falling to roughly where they were before the pandemic. After peaking in last summer's bull market at just under 5x sales, the median price-to-sales multiple in the third quarter came in at just above 2x sales.

Getting through, if not getting ahead

M&A activity in the just-completed quarter lines up more closely with the period coming out of the Great Financial Crisis than the head-spinning snap-back from the initial COVID-19 outbreak. A decade ago, the economy barely crawled out of the financial meltdown, with spending on tech transactions taking roughly four years to reclaim previous levels. The market's recovery from the pandemic, with free money flowing and confidence building from a tech-led rally, did not even take four months.

But the initial upswing out of the lockdown has reversed — and tech has been a pacesetter for both moves. It led the way up and, by several measures, is leading the way down, too. For some tech companies, it's just a matter that they have given back the gains they made during the pandemic's ephemeral "digital transformation" trend, while for others, the current economy is bringing more serious challenges. In either case, though, neither is in the mood to shop.

* Microsoft Corp.: The veteran vendor came into COVID-19 growing at a low-teens percentage rate but accelerated that to a high-teens rate in 2021. In its recent quarters, however, the company is barely hitting the teens, according to S&P Global Capital IQ. As growth has dipped, Microsoft has all but stopped acquiring. It has inked just three prints in 2022, putting it on pace for its lowest annual total (by far) since the recession-plagued year of 2010.

* Meta Platforms Inc.: For the first time in its history, the company formerly known as Facebook shrank this summer. In response, the company, which had nearly tripled revenue over the previous four years, instituted a hiring freeze along with other cost-cutting measures. M&A appears to be on that list. Meta has only announced a single deal so far in 2022, compared with the pace a decade ago when it was averaging an acquisition every month.

A significant reacceleration of tech M&A activity seems unlikely as long as the overall market remains weak. Pinched by persistent worries about inflation and recession, growth will be difficult for an industry that benefited from two years of exceptional expansion — both organic and inorganic. That record run ended this summer.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.