Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

7 Nov, 2016 | 09:45

Highlights

The SEC is nearing a decision that could threaten the business model of exchange operators or boost their growth by condoning higher market data fees.

The SEC is nearing a decision that could either threaten the business model of top exchange operators or accelerate their growth by condoning higher market data fees, adding more costs onto trading and other firms requiring live quotes.

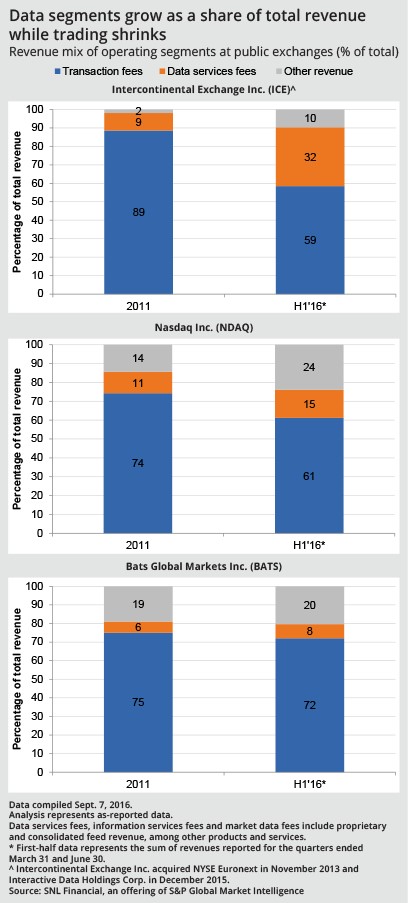

While trade execution services have dominated the top line for Intercontinental Exchange Inc., Nasdaq Inc. and Bats Global Markets Inc., the data feeds they provide to brokers and traders have driven revenue growth over the past several years.

The shift toward data is the result of two prevailing forces. More trades have occurred in alternative trading systems and dark pools, which enable institutional investors and traders to buy and sell large blocks of securities anonymously, eating into the business of the exchange operators. Meanwhile, exchanges have sought subscription-based revenue rather than volume-sensitive per-trade income.

Much of that recurring revenue has come from high-margin market data feeds, which broker/dealers rely on to parse supply and demand trends and build trading strategies.

For years, investment banks, trading firms and others have challenged the price of market data sold by Nasdaq and ICE's New York Stock Exchange, arguing that the rising costs indicate monopoly power.

Broker/dealers and the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association have opposed fee increases through lawsuits and eventually asked an SEC administrative court to review the data fees. The judge ruled in favor of the exchanges in a decision unsealed June 28, but SIFMA asked the SEC to review that decision on July 19. The commission agreed, and a final reply brief is due Dec. 7.

A reaffirmed SEC decision for the exchanges could open the door to more fee hikes. But if SIFMA's appeal succeeds, data customers could respond by demanding lower prices or even refunds.

Equity Dealers Association CEO Chris Iacovella described widespread frustration with data fees. "You really have the entire industry on the other side of the exchanges," he said in an interview.

Nasdaq declined to provide a detailed statement on the case or its market data feeds. In an email, a spokesperson for the NYSE said the company is "pleased" with the administrative judge's decision and "will continue to offer competitively priced market data services that customers value and demand." A spokeswoman for Bats Global Markets declined to comment.

SIFMA's argument has hinged on the idea that each exchange's feed provides a different data set, meaning no one feed is a true substitute for another. That, they have argued, allows an exchange to price its proprietary feed without competitive pressure, in effect creating a system of discrete monopolies.

Some data prices have risen dramatically at both NYSE and Nasdaq since 2014. In one instance, on Jan. 1, NYSE unbundled its Openbook Real-Time direct feed, which had an access fee of $5,000 per month, into four products with combined access fees of $12,000 per month. In January 2015, Nasdaq began charging subscribers who also operate ATSs up to $15,000 per month, unless they already paid at least that much in other depth-of-book fees.

At times the higher fees applied to third parties that pay to redistribute the data, including Thomson Reuters Corp. and S&P Global Inc., the parent company of S&P Global Market Intelligence.

The need for feeds

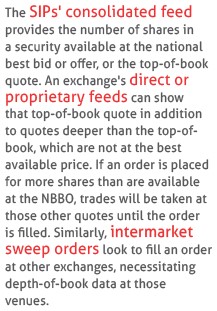

Selling market data is nothing new. When Regulation NMS established a national market system for equities trading in 2005, it proposed a consolidated data feed that would show the national best bid or offer, or NBBO, on a stock to all participants. The NBBO would be crafted by securities information processors, or SIPs, by taking trading data from the exchanges and re-issuing it in a consolidated format.

The SEC hoped the SIPs would ensure equal access to trade information for all investors. But because the three SIPs, two run by NYSE and one by Nasdaq, process data from different sources, they are inherently slower than the direct feeds, which exchanges continued to offer separately.

Traders who pay for an exchange's proprietary feed can access bids and offers for a stock earlier than the SIP. Exchanges cannot submit the data to their own proprietary feeds before the SIP, but direct feed customers see more timely quotes, rather than the "stale" SIP quotes, because the data has a nonstop path and uses faster infrastructure. That higher speed is usually augmented through co-location, in which traders' machines are placed in the same server banks as the exchanges'.

Direct feeds also provide depth-of-book data, in addition to a top-of-book bid and offer quote for a stock. That depth-of-book data shows quotes outside the best price and with different numbers of shares, essential context for the high-speed firms that act as market makers and provide much of the market's liquidity.

"What's happening three levels down, five, and sometimes 19 levels down, is as important or more important than the NBBO," Virtu Financial Inc. CEO Douglas Cifu said during a SIFMA conference panel in April. "The SIP is a completely worthless product to Virtu."

The faster proprietary feeds allow firms to "synthetically create" a better NBBO to trade on, Eric Hunsader, a trading software developer and critic of high-speed trading, said in an interview. Hunsader won a whistle-blower award earlier in 2016 for proving that NYSE sent data to its direct feed before the SIP, resulting in the first SEC fine ever levied on a stock exchange.

"Do [market makers] need to take the proprietary feed from most of the big exchange groups? Yeah, they do," Andrew Upward, head of market structure at investment bank Weeden & Co., said in an interview.

The question facing the SEC, however, is whether firms need to take every proprietary feed. The commission's final decision could curb this lucrative business' growth or give exchanges more leeway to raise prices.

"If the decision is upheld, obviously the exchanges will have a clearer path to continuing or exercising pricing pressure," said Daniel Connell, managing director of market structure and technology at Greenwich Associates. On the other hand, he said, raising prices too much could bring another wave of unwanted focus on the exchanges.

The M-word

If each separate direct feed provides a unique data set, a high-speed trader needs each feed to make markets effectively across the different trading venues. Otherwise, a firm could substitute one for another.

But if, as SIFMA and its allies have argued, the feeds are not substitutes, they function outside of the competitive forces that ordinarily keep prices in check.

The exchange groups have denied that characterization, but Nasdaq CEO Robert Greifeld at a conference in April used the word "monopoly" in a discussion about exchanges' ability to set market data prices. Channeling broker/dealers' complaints, the event's moderator asked Greifeld why data fees continue to rise. Greifeld responded by describing a new, lower-cost feed product, Nasdaq Basic. (Nasdaq notes on its website that Basic is not meant for active traders who need depth-of-book.)

"People still complain," the moderator said.

"I hear you," Greifeld responded. "And I think exchanges that have monopoly positions have pricing power, and it's not just in data." When asked to comment on Greifeld's statement, a Nasdaq spokesperson said the company does not claim to have a monopoly in any part of its business.

SEC Chief Administrative Law Judge Brenda Murray's ruling in favor of the exchanges was disclosed June 28. A SIFMA spokeswoman had no comment beyond the organization's petition for reviewing Murray's opinion.

In her decision, Murray wrote that the largest depth-of-book customers are able to pressure exchanges into setting competitive prices by threatening to send their trade orders, the "life blood" of an exchange, elsewhere.

In an email to Nasdaq from one trading firm, whose name was redacted in the court document, the firm warned it would pull its significant order flow if Nasdaq went through with a depth-of-book price increase. When Nasdaq raised the price, the trading firm stopped routing orders there. But, as SIFMA's lawyers noted, that threat did not actually prevent the price increase.

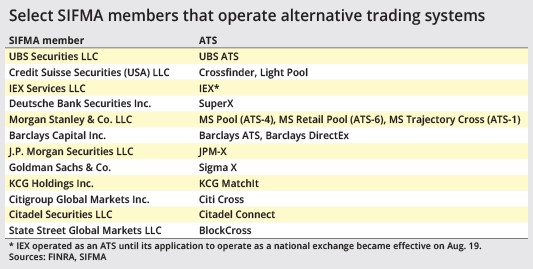

Conflicts of interest

About 100 "large banks and electronic trading firms" conduct more than 90% of all trading on Nasdaq's equities venues, one of the post-hearing briefs states. Those banks and traders are also among SIFMA's largest members, Nasdaq's lawyers pointed out in the same post-hearing brief, and some operate the alternative trading systems that have siphoned trading activity away from exchanges in recent years. Such firms have a clear self-interest in undermining established venues, the exchanges have argued.

Because its members directly compete with the traditional equities exchanges for trading business, SIFMA's attempts to handicap the exchanges' market data businesses should be viewed as a conflict of interest, Nasdaq wrote. "When rivals make anticompetitive use of antitrust law or other regulatory frameworks to impair rivals, the public interest is disserved," its legal team argued.

Meanwhile, SIFMA and its supporters point out that the committee charged with overseeing data prices is composed of the exchanges themselves in their capacity as self-regulatory organizations.

Some believe the issue could be partly resolved by requiring exchanges to route their proprietary direct feeds through the same servers and infrastructure they use for the SIP. "If you remove the latency difference, at least you make the top-of-book feeds far more compelling," said David Lauer, a former high-speed trader and the chairman of the Healthy Markets Association.

Another way to make the faster direct feeds less advantageous could be to speed up the SIPs. In October, Nasdaq migrated its SIP to new hardware that drastically reduced the feed's latency; it also proposed a new price schedule to accompany the upgrade. Bats Global Markets called the fees unnecessary in a comment letter to the SEC, writing that they only served to pad revenue for Nasdaq.

Nasdaq's plan to improve its SIP should help, Weeden & Co.'s Upward said before the upgrade took place. But it would take structural change to address the root problem.

"No matter how fast NYSE or Nasdaq makes their SIP feeds, they're always going to be slower than the proprietary feeds," he said.