Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY — Dec 07, 2023

Globally, output price inflation edged higher in November, according to PMI® data compiled by S&P Global across over 40 economies and sponsored by JPMorgan, though remaining among the weakest seen over the past three years.

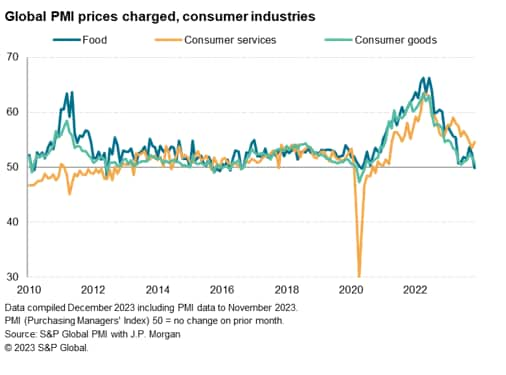

Goods selling price inflation remains especially low by historical standards, with food prices notably falling for the first time since early 2020. However, service sector inflation continues to run somewhat elevated, in part linked to wage effects.

Importantly, the surveys indicate that the overall demand environment remains subdued, and global demand-pull price pressures have now consequently fallen close to their long-run average. Employment growth has meanwhile stalled as firms grow concerned about excess capacity, which should cool wage growth.

These are therefore trends which hint at weaker core inflation pressures in the months ahead, albeit with the inflation trend looking more stubborn in the UK than in the US and Eurozone.

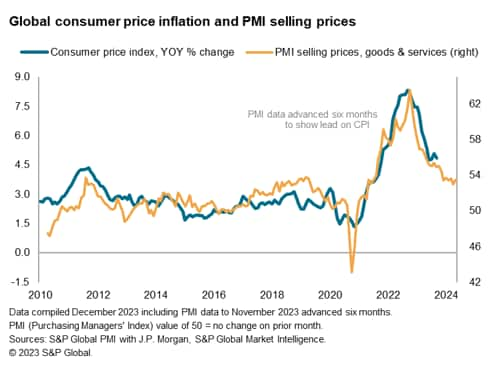

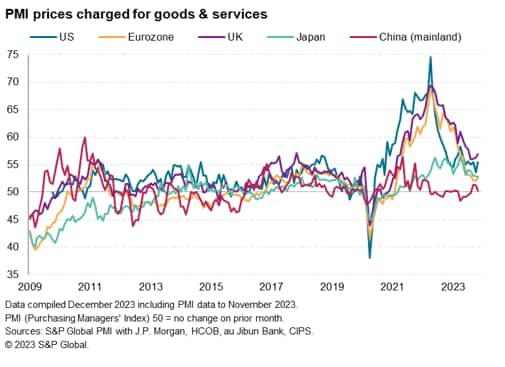

Average prices charged for goods and services rose globally at a slightly increased rate in November, though the pace of inflation remained among the weakest recorded over the past three years. The global PMI selling price index - compiled by S&P Global and covering prices charged for both goods and services in all major developed and emerging markets - edged up from 53.0 in October to 53.5, which compares with an all-time high of 63.5 back in April 2022 but remains somewhat elevated compared to the survey's ten-year pre-pandemic average of 51.2.

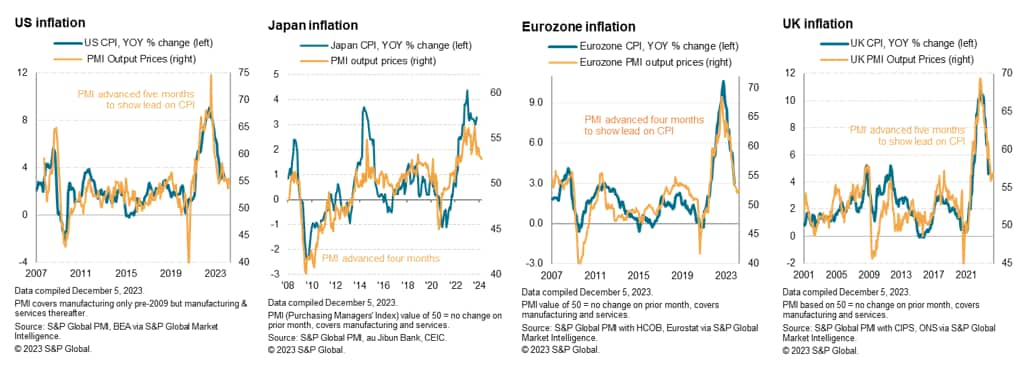

The leading-indicator properties of the PMI mean that global inflation is signalled to cool further to around 3.5% early in the new year, though to then remain at this rate in the near-term. That compares with a pre-pandemic ten-year average of 2.6%.

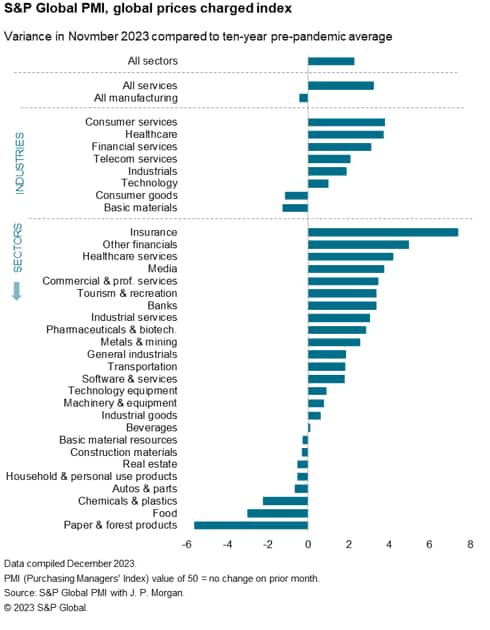

Looking at sector divergences, average selling price inflation for goods fell further below its long-run average, reflecting healed supply chains, inventory reduction and recent falls in oil prices.

However, the rate of service sector inflation remained elevated by historical standards, and even accelerated slightly - albeit still running at one of the lowest rates seen over the past three years and far below recent highs.

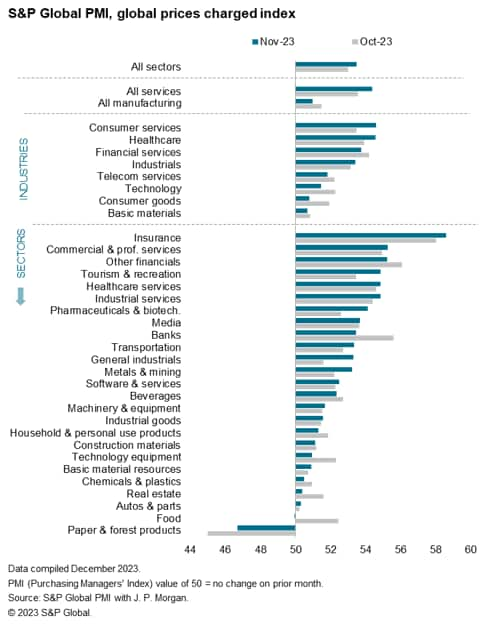

Looking in more detail, at a broad industry level, consumer services and healthcare reported the joint-strongest rise in prices charged during November followed financial services. The softest rate of inflation was seen for basic materials, which is a sector that has suffered especially weak demand in recent months, followed by consumer goods.

At a more granular level, prices fell in only two of the 25 sub-sectors covered by the PMI - forestry & paper products and, to a lesser extent, food - but rates of increase cooled in a further nine sectors. The steepest price hikes were seen in insurance, commercial & professional services and 'other financials' (which encompasses all financial services excluding banking, insurance and real estate).

Looking at the latest data compared to the average rate of inflation seen in the decade prior to the pandemic, eight sectors are seeing the Prices Charged Index now print below the pre-pandemic average, and only 13 are now seeing the PMI selling price inflation index more than onc index point higher than the pre-pandemic average.

Besides paper & forest products, the biggest disinflationary force relative to pre-pandemic standards is now emanating from food production, the rate of increase of which fell into negative territory in November for the first time since May 2020 (and prior to that, August 2016).

If sustained, falling food prices will help further alleviate upward pressure on household cost of living pressures, and also help cool cost growth in sectors such as hotels and restaurants.

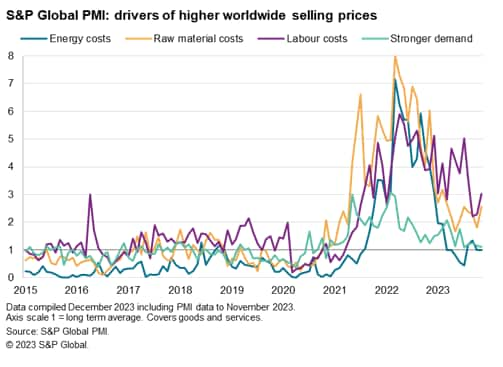

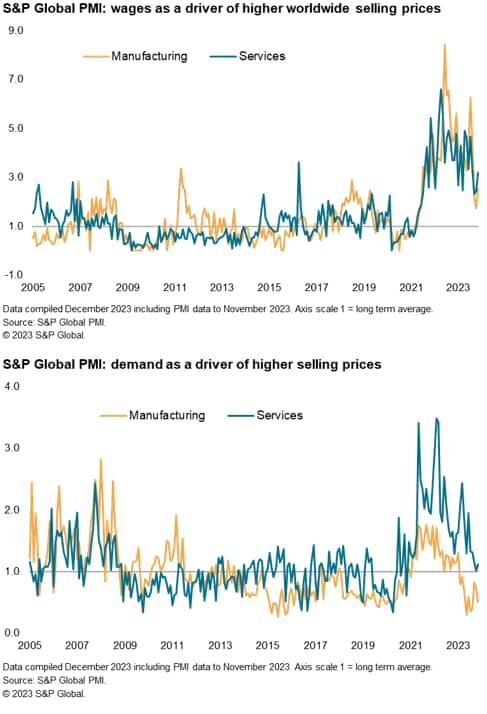

Analysing the most widely cited factors as having driven charges higher, labour costs remained the most commonly reported cause in November, with the incidence of wage-push price hikes rising on the prior two months yet running well below recent highs in both manufacturing and services.

Energy meanwhile remained the lowest upward price force, linked to lower oil prices.

Raw material price inflation edged higher, in part reflecting fewer cases of inventory-reduction linked to discounting and cases of tighter supply, but remained modest by recent standards.

Perhaps most importantly, demand-pull inflationary forces moderated. Lower final demand has eroded pricing power from manufacturers over the past ten months - as proxied by price pressures dropping below their long-run average. Upward demand pressure on prices in the service sector have also fallen close to their long-run average in recent months. The overall demand-pull effect on global prices consequently sank to the joint-lowest for three years, close to the long-run average.

Looking at price trend variations around the world, the stickiest inflation is evident in the UK, according to the PMI's composite selling price index. A further rise in the rate of inflation suggests headline CPI inflation could stick at just over 4% in the early months of 2024.

Better progress towards central bank 2% targets has meanwhile been signalled in the eurozone and US. The eurozone PMI's selling price index also lifted slightly in November, but remained broadly indicative of CPI running close to 2% as we head into the new year. Similarly, a small rise in the US index hinted at some stubbornness of inflation, but pointing to CPI only modestly above 2%.

In Asia, the PMI hints at inflation cooling below 2% in Japan in the coming months, while in mainland China the PMI selling price index remains indicative of stable prices.

Access the Global PMI press release here.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, S&P Global Market Intelligence

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

© 2023, S&P Global. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI®) data are compiled by S&P Global for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

Location