Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY — Feb 01, 2024

Global manufacturing supply chains lengthened in January for the first time in a year, according to PMI survey data. Disruptions to shipping in the Red Sea compounded supply delays linked to constrained traffic in the Panama Canal and adverse weather in the US. Raised shipping costs fed through to price hikes.

However, even in economies most badly affected by the Red Sea crisis, notably the UK and Eurozone, the extent of supply delays and the impact on prices has so far been far less marked than seen during the pandemic. Globally, output also rose, albeit marginally, for the first time in eight months.

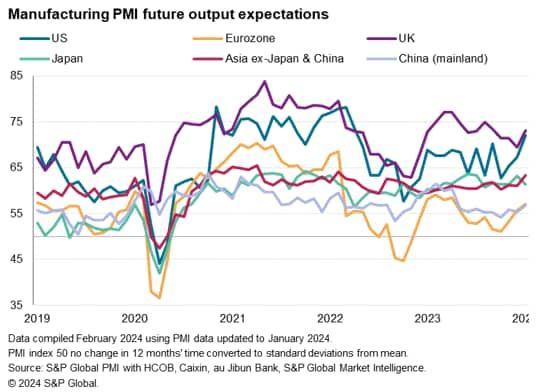

While there remains scope for Red Sea and wider Middle East tensions to intensify in coming months, the situation witnessed so far in January failed to deter manufacturers to become more optimistic about the year-ahead outlook. Confidence lifted worldwide to its highest since last April and moved above its long-run average. Despite the supply concerns, manufacturers are looking to stronger demand and a shift in the inventory cycle to boost growth in 2024.

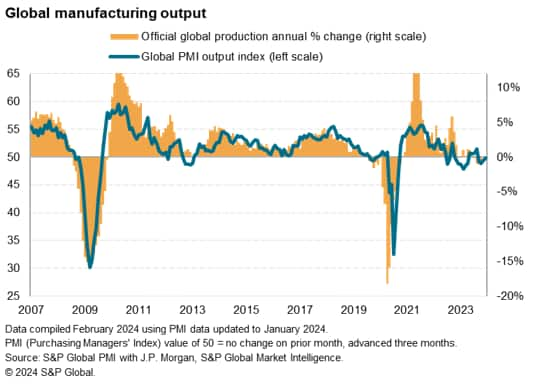

Global manufacturing output edged higher in January, ending a seven-month downturn, according to the latest PMI surveys compiled by S&P Global and sponsored by JP Morgan.

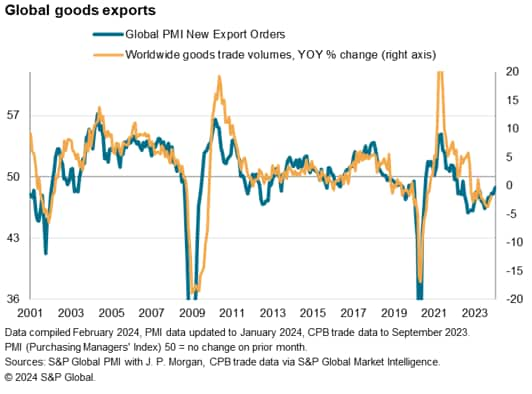

The January survey also brought some news of the demand downturn moderating. Although new orders fell for a nineteenth successive month, the decline was only marginal and the smallest recorded over this period. Similarly, while new export orders fell for a twenty-third straight month, the latest deterioration was the smallest seen since June 2022.

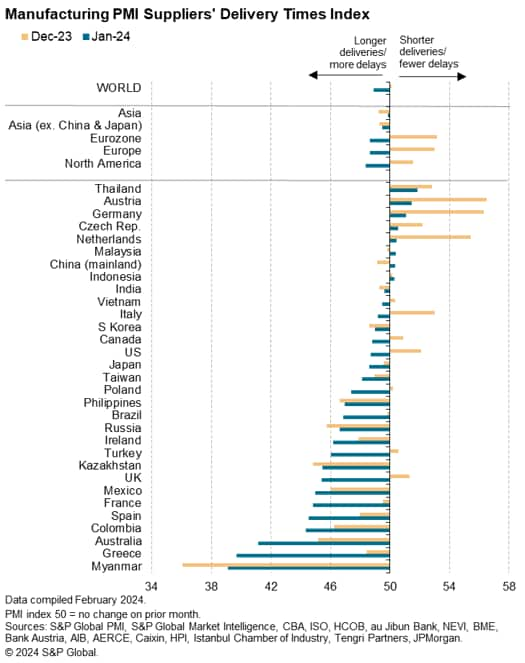

Global manufacturing output rose despite a deterioration in global supply chains. Average supplier delivery times lengthened worldwide in January for the first time in a year, with companies often linking delays to the diversion of shipping away from the Red Sea, with additional supply constraints attributed to the adverse weather in the US and the throttling of traffic through the Panama Canal.

Importantly, the overall incidence of delays remains far short of those typically seen during the pandemic. While any reading of the suppliers' delivery times index below 50 signals longer lead-times than a month ago, the January reading of 48.9 hints at few issues on a global scale when compared with a record-low of 34.7 in October 2021 and an average of 39.8 over 2021 and 2022.

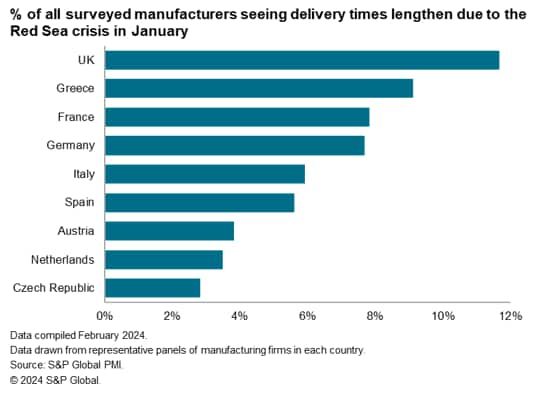

Some economies have naturally been harder hit by the Red Sea disruption than others. Analysis of the reasons cited by PMI panel member companies reveals that the Red Sea crisis had an especially marked impact on European companies in January, which makes sense as it is the diversion of ships from Asia to Europe that are primarily affected by the Houthi militia attacks in the Red Sea. Instead of passing through the Suez Canal, many of these ships are being re-routing around the Cape of Good Hope, which adds almost two weeks for most Asia-to-Europe trips.

Out of the European countries monitored, UK producers were the worst impacted by the Red Sea crisis. In total, 12% of the manufacturing PMI survey panel reported that delivery times had worsened due to the crisis, swiftly followed by Greece (9%), France and Germany (both 8%).

Supplier delivery times consequently lengthened in the UK and eurozone to the greatest extent since November 2022, albeit even in these cases to far lesser extents than seen during the pandemic. Delivery times even continued to shorten in Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and the Czech Republic, though to lesser degrees than prior months.

However, additional issues - notably adverse weather in North America and drought-related shipping restrictions in the Panama Canal - meant supplier delivery times also lengthened in the US for the first time since December 2022 and extended to Canada. Australia was also hit harder than average by global shipping related issues.

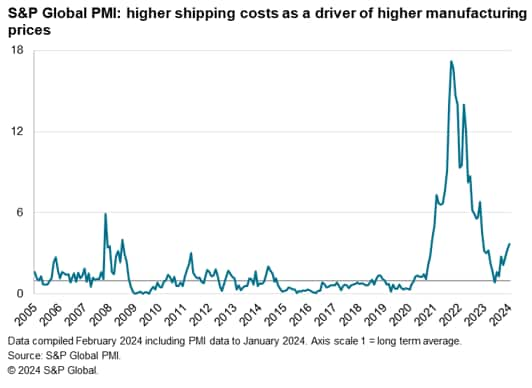

Although modest overall in January, these shipping issues fed through to some upward price pressures. Comments tracked in PMI survey responses reveal that the number of companies worldwide reporting that they have raised their selling prices due to increased shipping costs is running at 3.7 times the long-run average. Although far from the peak price pressures from shipping seen during the pandemic, this represents the highest upward trend since 2008 if pandemic months are excluded.

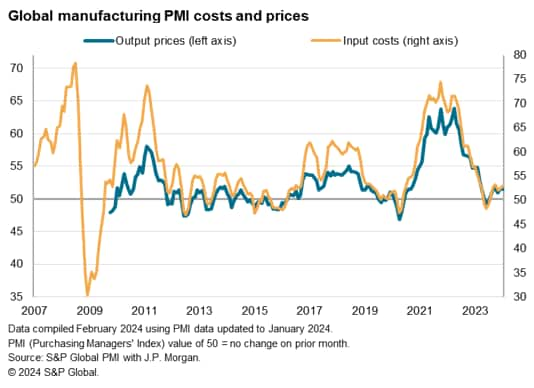

Measured overall, manufacturing input costs consequently rose globally for a sixth straight month in January (having fallen in the three months to last July), increasing at the fastest rate since last October.

These higher costs in turn fed through to a sixth consecutive month of rising factory selling prices. However, in a sign that the inflationary impact of the shipping issues remains contained, for now at least, the rate of selling price inflation was unchanged from December and only marginally above the survey's pre-pandemic average. The latest increase hinted at only modest price growth, especially when compared to the price spikes seen during the supply disruption of the pandemic.

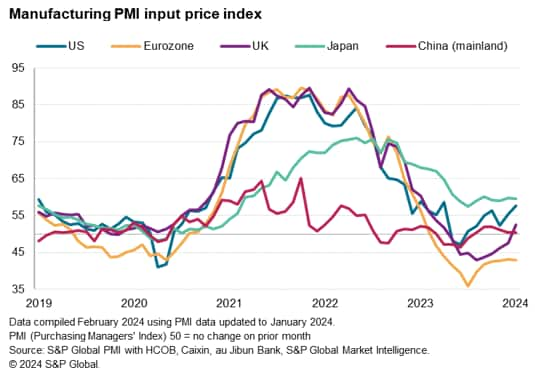

There are some hot spots in terms of cost and price growth, in part reflecting the regional variations in supply delays, which are worthy of further mention and monitoring. Input cost inflation picked up notably in the UK (where costs rose for the first time since last April) and the US (where prices rose to the largest extent since last April), though further price falls were noted in the eurozone. Input cost inflation meanwhile edged lower in Japan and prices barely rose in mainland China for a second consecutive month.

The January PMI data therefore hint at only a modest impact from the disruption to shipping in the Red Sea both on supply chains and prices so far, albeit with some economies - notably the UK - seeing a somewhat more material impact than others. The exacerbating impact on global delivery delays from adverse weather in the US is meanwhile a factor that should fade in coming months.

The concern is that tensions around the Israel-Gaza war are likely to disrupt shipping in the Red Sea at least into the second quarter, and any potential escalation of the war in the Middle East may drive up energy prices.

There is also the potential for the Red Sea-related shipping delays to cause problems further down the line, in terms of ships and containers being unavailable due to port congestion and changes to schedules, causing problems for other countries beyond Europe.

Any protracted shipping disruption could therefore add to global price pressures at a time when central banks are considering the appropriateness of lower interest rates, especially if energy prices also move higher. Although these are supply side factors which are in theory not influenced by monetary policy, policymakers are keen to ensure inflation expectations remain anchored, and hence may see the need to at least delay rate cuts if goods prices continue to rise through the first half of 2024.

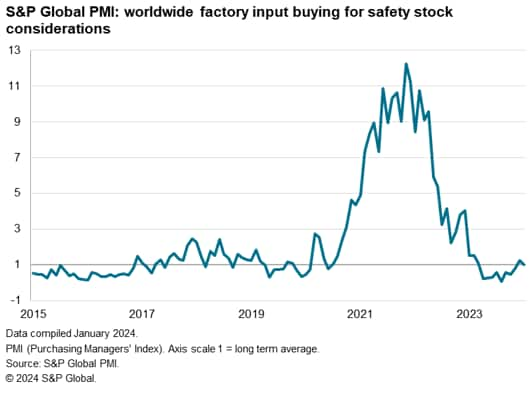

Encouragingly, however, as of January there are few signs that manufacturers are overly concerned by the shipping issues. Importantly, the anecdotal evidence provided by PMI contributing companies found no signs of factories building safety stocks, hinting at few fears of supply disruptions causing problems with future fulfilment of orders. This constraint on production had been a key mechanism of price rises during the pandemic.

Similarly, rather than becoming gloomy due to the shipping problems, firms' expectations of output growth over the coming year picked up in January to reach the highest since last April.

It's also worth noting that even some of the economies hit hardest by the Red Sea disruptions, specifically the UK and eurozone, also reported improved business prospects for the coming year.

While the Red Sea attacks are clearly adding a fresh area of concern to those manufacturers reliant on shipping, the survey is therefore recording broader areas of optimism among producers, notably surrounding improving global growth prospects amid the easing cost of living crisis (and associated cut to interest rates) but also from a shift in the inventory cycle.

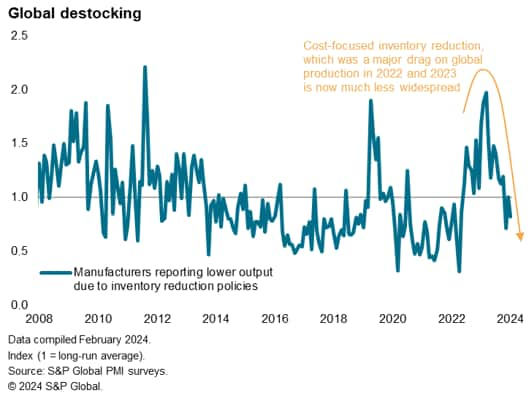

The uplift in global future expectations was accompanied in January by the global PMI survey's forward-looking orders-inventory ratio edging up to its highest since May 2022. At the same time, the number of companies deliberately reducing inventories due to cost considerations has fallen sharply in recent months. While inventory reduction was a major drag on production from late 2022 through much of 2023, the three months to January have seen some of the lowest incidences of this inventory-driven drag since mid-2022.

This shifting focus away from inventory reduction suggest that the inventory cycle will be more supportive to manufacturing growth in 2024, barring any setbacks to global demand. It will be important to assess the developing trends in supply, demand, inventories and prices through the PMI surveys in the coming months to see whether manufacturing will indeed prove resilient to the shipping disruptions.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, S&P Global Market Intelligence

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

© 2024, S&P Global. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI®) data are compiled by S&P Global for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

Location