Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

ECONOMICS COMMENTARY — May 19, 2022

The new export orders index from S&P Global's PMI business surveys tracks foreign demand for both goods and services. The data can be used to gauge export demand over time across countries and sectors.

The new export orders index can also be aggregated to provide a useful and timely guide to global or regional trade flows, allowing insights into changing demand conditions well ahead of comparable official data.

Purchasing managers participating in S&P Global's PMI business surveys, conducted in 44 countries, are asked how the volume of new export orders has changed compared to the prior month on average. The precise question wording is:

"Is the level of new orders received for export this month higher, lower or unchanged on average than one month ago?

"This refers to the volume of new orders/business (in units/volume terms) from customers outside of your country."

Companies are also asked to provide a reason for any change, if known.

The identical question is asked in both the manufacturing and services PMI surveys, as well as in the construction PMI survey where conducted.

Note that the question refers to the flow of new business received from abroad via orders, not actual physical shipments in each month. The latter will typically occur with a lag, or lead time, depending on the availability of the product and the necessary arrangements for fulfilment and shipping.

In a manufacturing company, goods exports are readily quantified as those to be shipped to non-domestic customers. In a service sector company, exports will vary depending on the sub-sector, but will include activities such as consultancy work provided to foreign customers as well as many travel and tourism related activities and financial services activities.

Note that services exports will often be harder for survey respondents to quantify in volume rather than value terms.

The percentage of responses are weighted to derive a 'diffusion index' as follows:

INDEX = (percentage of survey panel responding 'higher') + (percentage responding 'no change'*0.5)

Hence readings of 50 indicate no change in new export orders on the prior month, readings above 50 indicate an increase and readings below 50 indicate a decline.

The index is also seasonally adjusted to strip out normal variations in demand for the time of year (we utilise the widely used US Census Bureau X-12 ARIMA software for removing seasonality).

To ensure the survey data are as representative as possible, in each country the panel of companies is carefully selected to accurately represent the true structure of the chosen sector of the economy as determined by official data.

A weighting system is also incorporated into the survey database that weights each response according to the size of sector in which a company operates, and by its workforce size. The survey panels therefore replicate in miniature the structure of the sector being monitored.

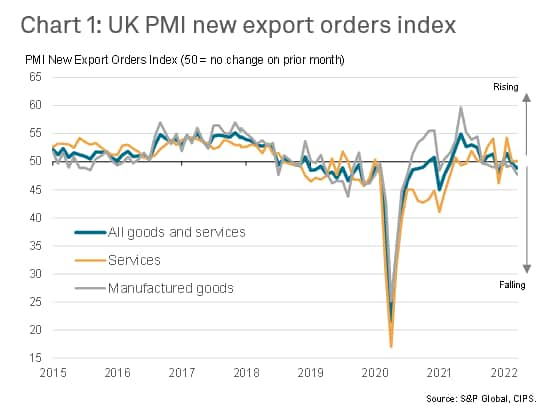

The PMI new export orders index allows us to track international demand for a country's goods and services on a timely, monthly, basis. As an example, chart 1 shows the composite new export orders index for the UK, along with its two major components of manufacturing and services, up to April 2022.

In the example of chart 1, strong growth of UK exports of goods and services was recorded from mid-2016 through to mid-2018, after which exports first stalled and then fell into decline; a downturn which accelerated sharply - to an unprecedented degree - during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. UK exports of goods recovered early in the pandemic, though the recovery was volatile amid new waves of the virus. Services exports only started to recover to any noteworthy extent in late-2021 and early-2022, with the Delta and Omicron waves resulting in faltering upturns.

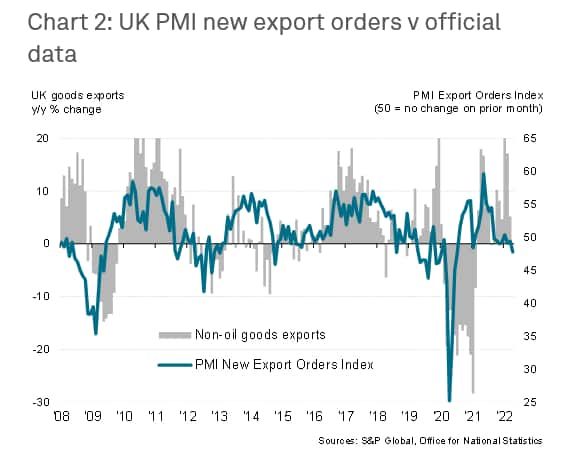

The survey data can therefore help us to understand the changing direction of official data on trade for any given country, with the PMI signals having the advantage of being available almost two months ahead of most comparable official updates. Often there are no high frequency official data on trade in services.

Both charts 2 and 3 plot manufacturing PMI new orders data against official export data, in these cases hinting at imminent slowdowns of exports out of the UK and Germany in the wake of the Ukraine war.

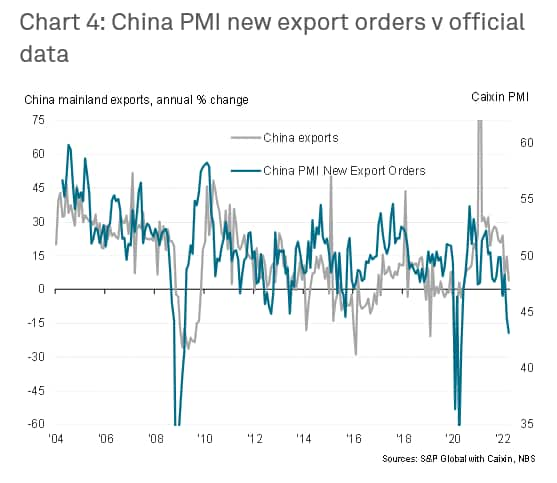

Chart 4 meanwhile plots the PMI for mainland China, produced by S&P Global for Caixin, against comparable official data. The PMI data point to a steepening downturn in exports in April 2022 amid lockdowns designed to inhibit the spread of the Omicron variant.

Some caution is often needed when comparing survey data with official numbers.

Frist, bear in mind that the PMI excludes energy and agriculture, so try to compare like-for-like where possible.

Second, the PMI data tend to show smoother trends than the official data, the latter being susceptible to large swings due to changes in certain high value sectors (such as aircraft shipments or precious items). Therefore, the PMI is often best used as a gauge of the export trend, rather than a precise guide to month-on-month variations.

Third, official data tend to get revised after first publication - sometimes quite significantly.

Fourth, remember that the PMI records export orders, not shipments, as it is the latter which is measured by the official data.

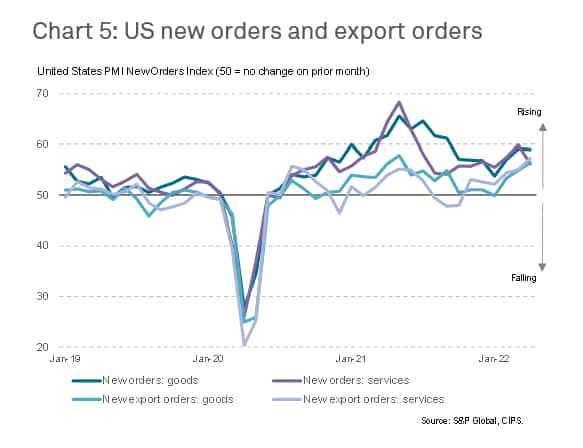

It is also useful to compare the PMI new export orders index with the broader PMI new orders index, the latter tracking orders from domestic as well as export customers. As the example in chart 5 shows, after the initial pandemic downturn in demand seen in early 2020, growth of export orders has lagged overall new orders growth for both goods and services in the US. Exports of services have been especially subdued (attributable to pandemic travel restrictions limiting scope for exports of more labour-oriented services and curbing tourism and leisure). However, in early-2022, exports of services have revived amid looser pandemic restrictions. A commensurate slowing in overall new orders growth for services therefore hints at domestic demand for services having weakened.

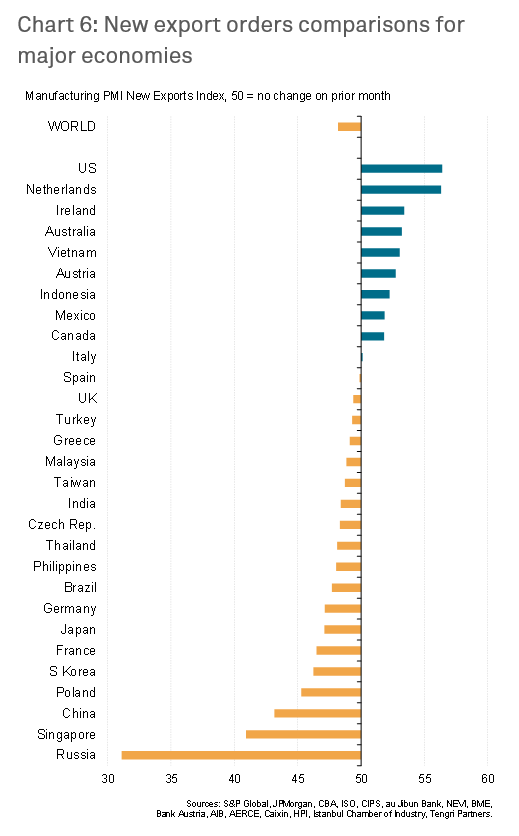

The use of the same PMI survey methodology in each country facilitates international comparisons of export performance. For example, chart 6 ranks countries by their manufacturing new export orders performance.

Chart 6 illustrates how the US was reporting the strongest growth in new export orders in April 2022 of all the economies covered by the S&P Global PMI series, followed very closely by the Netherlands. In contrast, Russia reported the steepest decline, followed by Singapore and mainland China.

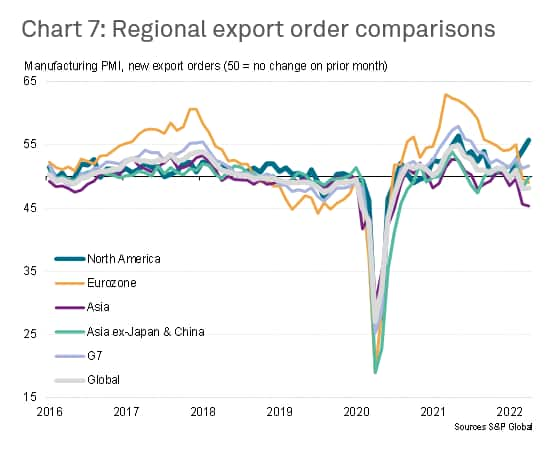

The use of identical national methodologies also facilitates the aggregation of data into international, regional and global indices by weighting each country's new orders index by the size of their GDP.

Hence, export trends can be compared and tracked by region of the world, as demonstrated by chart 7. Note that eurozone exports include intra-regional trade between the member states.

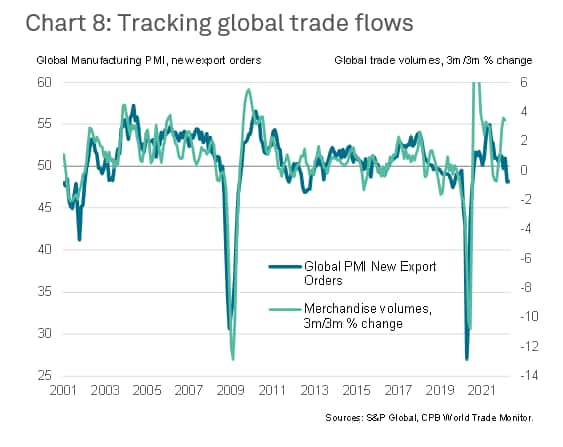

The aggregating of the PMI data into an index of global export order trends is in fact one of the most widely used applications of the data. Chart 8 plots the global PMI new orders index against official trade volume data, as compiled by the CPB World Trade Monitor from individual national statistical agencies. The PMI acts as an accurate leading indicator of changes in global trade volumes, proxying the rate of growth in advance in all bar the most extreme occasions such as the pandemic, and even in such unusual times the PMI provides an early indication of turning points in the trade cycle.

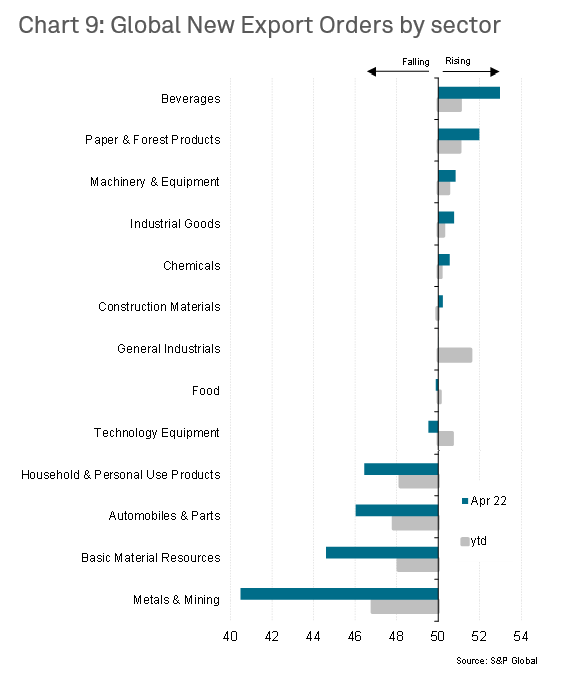

Further insight in trade flows can be gleaned from the PMI detailed sector data, which track new export orders for individual sectors at the global, US, European and Asian levels. This allows the cross-sectional analysis of trade at any given time, as shown by the global sector rankings in chart 9.

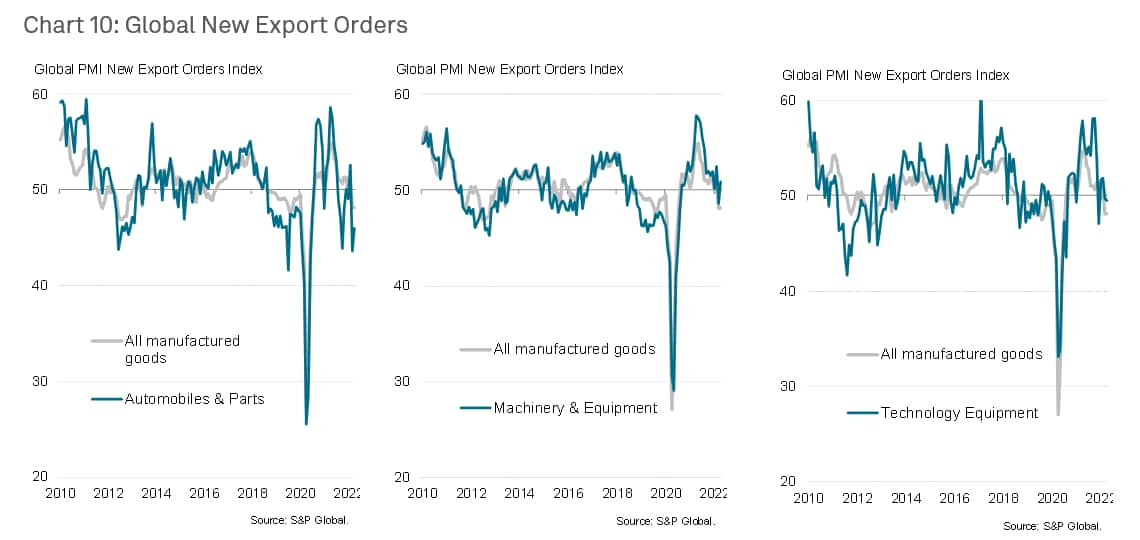

Alternatively, the sector PMI data can be used for time series analysis, as illustrated by global exports of specific products over time, as in chart 10, with the broader global all-manufacturing new export orders index providing a readily-available benchmark for relative industry performance.

Chris Williamson, Chief Business Economist, S&P Global Market Intelligence

Tel: +44 207 260 2329

chris.williamson@spglobal.com

© 2022, IHS Markit Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited.

Purchasing Managers' Index™ (PMI™) data are compiled by IHS Markit for more than 40 economies worldwide. The monthly data are derived from surveys of senior executives at private sector companies, and are available only via subscription. The PMI dataset features a headline number, which indicates the overall health of an economy, and sub-indices, which provide insights into other key economic drivers such as GDP, inflation, exports, capacity utilization, employment and inventories. The PMI data are used by financial and corporate professionals to better understand where economies and markets are headed, and to uncover opportunities.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

Location