Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

BLOG — Apr 13, 2023

Following the spectacle of ocean container shipping being thrust into public view during the COVID-19 pandemic, thanks in no small degree to chiding from President Joe Biden, the legislative impact still lingers. The long-term impact of container shipping's moment in the sun — and in the crosshairs of regulators — will come down to which of two starkly divergent versions of reality carries sway in Washington, DC, in the coming months.

Congress is considering legislation to strip carriers of antitrust immunity that, if passed, would likely shake up the industry structure by making it harder to operate in alliances or even vessel-sharing agreements. The debate will be framed along these lines: Are ocean carriers indeed the malevolent actors they are made out to be — "cartels" that were engaged in collusion and price gouging that jacked up freight rates and achieved historically high profits for themselves at the expense of American businesses, and by extension, consumers?

Or were the unprecedented rates and profits seen during the pandemic, however extreme they might have been, merely the result of the same forces that have always determined results in the industry, good, bad, or ugly? In other words, was this simply a case of demand exceeding supply?

But for many within the industry watching this debate play out, it's not a question of which of the two divergent views hold the most merit. The real question is a more fundamental one: Will reality prevail over politics? Given that what is at stake is nothing less than the future structure of the industry, reality matters.

Many believe that a loss of antitrust immunity would trigger yet another round of industry consolidation as carriers withdraw from alliances and even vessel-sharing agreements to avoid legal risk, with the fleets of second-tier carriers being too small to compete with the top-tier carriers, forcing them to merge.

In other words, real world impact would result. But ever since Biden quipped last year that he wanted to "pop" carriers for raising rates ten-fold, reality was set aside as carriers proved a convenient scapegoat for problems such as inflation that threatened the Democrats' performance in the 2022 mid-term elections.

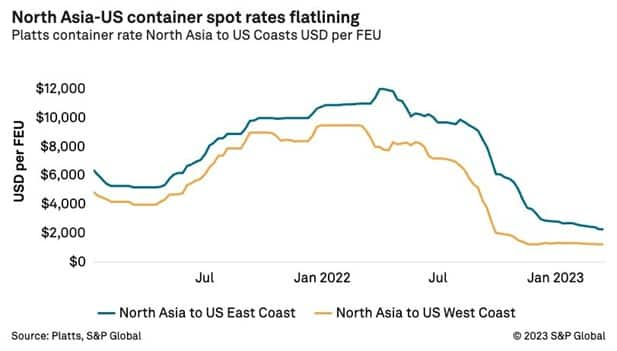

Not that it mattered, but the inconvenient truth was always very different and remains so today. Rates and profits spiraled upwards due to a consumer spending surge and capacity being removed from the market as ships were forced to wait for berths outside congested seaports. Of course, as soon as those conditions eased, rates promptly collapsed, falling over 90 percent in the trans-Pacific trade since last year, according to Platts, a sister product of the Journal of Commerce within S&P Global. Supply and demand drove the market up and then back down again.

"While prices have risen for ocean-borne shipping, this is largely a figment of simple supply and demand economics as cargo volumes have hit unprecedented levels during the pandemic," Greg Regen, president of the AFL-CIO Maritime Trades Department, said in a letter to the Senate last year opposing revocation of antitrust immunity. "It is not accurate to suggest that the ocean carriers have engaged in price fixing, or that agreements between carrier alliances include rate-setting schemes that would result in price increases."

But even the stated opposition of labor, an ally of Democrats, has not dimmed the zeal of legislators to punish ocean carriers for the pandemic disruptions. During his State of the Union address in January, Biden urged Congress to "finish the job," going beyond last year's Ocean Shipping Reform Act of 2022 (OSRA-22) by passing "bipartisan legislation to strengthen antitrust enforcement."

That call was answered in late March, with Rep. Jim Costa, D-Calif., introducing legislation to do exactly that. "For far too long, foreign shipping monopolies have manipulated the ocean shipping industry and employed unfair trade practices, hurting American exporters and consumers," Costa said in a statement following the bill's introduction. "Collusion" is one of the practices the legislation aims to prevent.

The only problem is it's not true. If collusion has occurred, it hasn't been visible to the agency with the most knowledge of the industry, the US Federal Maritime Commission (FMC).

The trans-Pacific trade "is not concentrated, and the increased rates in that market are the result of an extreme spike of consumer demand … that overwhelmed the supply of ship capacity," the FMC said in its Fact Finding 29 study release last May, which focused on the impact of COIVD-19 on containerized supply chains.

"Even after increasing our reporting and analysis, there's no evidence" of collusion or price fixing by carrier alliances, FMC Chairman Daniel Maffei told the Journal of Commerce's TPM22 conference last March.

If, in fact, carriers have been colluding, it's difficult to see how it did them any good. During the two decades from 1995 to 2016, shipping lines earned low-single-digit returns on invested capital, much lower than marine terminals, freight forwarders, truckers, or railroads, according to a Capital IQ and McKinsey analysis. Inadequate profitability drove a series of mega-mergers during that time period, resulting in the 10 largest carriers controlling more than 80 percent of capacity.

Furthermore, if there were collusion, the Department of Justice presumably would have found some evidence thereof. Although the DOJ is now believed to be actively investigating again, a multi-year grand jury investigation that included an FBI raid on a Box Club meeting of carrier CEOs in 2017 failed to yield indictments and is believed to have been wound down in 2019.

If shippers were concerned about ocean carrier behavior, it was more likely focused on the impact of too much competition, in the sense that chronically low rates would impact service or lead the industry to over-consolidate, reducing competition and choice.

"There is not anticompetitive behavior in the ocean container shipping industry," Jim Newsome, former president and CEO of the South Carolina Ports Authority, told the Journal of Commerce. "The major carriers have been well-scrutinized under European, Asian, and US regulatory regimes over the last 20 years as antitrust immunity for pricing was removed. The market will continue to define the level of rates."

We'll soon find out whether or not that matters.

Correction: A previous version of this story referred to Jim Newsome as president and CEO of the South Carolina Ports Authority; Barbara Melvin succeeded Newsome as president and CEO in July 2022.

Subscribe now or sign up for a free trial to the Journal of Commerce and gain access to breaking industry news, in-depth analysis, and actionable data for container shipping and international supply chain professionals.

Subscribe to our monthly Insights Newsletter

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

How can our products help you?