Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

BLOG — Mar 24, 2023

By Thea Fourie

Inflation is expected to remain elevated longer in Sub-Saharan Africa than in other regions.

In line with the global trend, central banks of major African economies including South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, and Kenya tightened their monetary policies in 2022, leading to higher interest rates. Interest rates are, nonetheless, expected to decline in Angola, Ghana, Mozambique, and Uganda during the second half of 2023.

Access to global financial markets has become more difficult, especially in countries experiencing debt distress such as Ghana, Malawi, Ethiopia, and Zambia. The region also saw increased requests for multilateral support and debt restructuring.

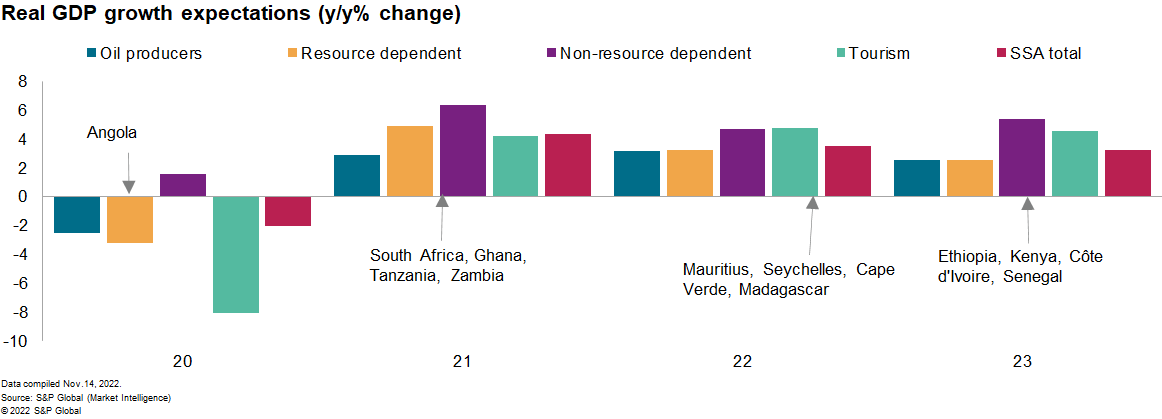

Real GDP across Sub-Saharan Africa is expected to drop to an average of 3.3% in 2023, as global growth slows to 2.2% from around 3% in 2022.

The cancellation of COVID-19 policies in mainland China—a key regional trading partner and the world's largest consumer of commodities such as food and oil—could support overall emerging market growth, expected to rise marginally to 3.8% in 2023 from 3.6% in 2022. Economic recovery is now anticipated in mainland China, and along with low inventory levels across multiple commodities, global commodity prices are expected to stabilize from second half 2023 onward.

Headline inflation in Sub-Saharan Africa will average 10.3% in 2023 compared with 13.1% in 2022. This level exceeds the region's five-year average of 9.2% and discourages any rapid movement toward loosening monetary policy.

Also supporting regional economic growth is investor interest in natural gas, especially in Mozambique, Tanzania, Republic of the Congo, and Cameroon/Guinea-Bissau as Europe cuts off Russian gas imports. Senegal is expected to become one of the best-performing countries in the region in terms of GDP growth during 2023 with the commencement of natural gas exports.

Debt consolidation stalled

The surge in global commodities prices in 2021 gave room to Sub-Saharan Africa countries to adopt fiscal consolidation measures as tax proceeds, particularly from the mining sector, boosted government revenue. But government policies enacted to address high food and fuel costs—including fuel subsidies, price caps on food products, and cash transfers—stalled fiscal consolidation around the region.

Consequently, the fiscal deficit in 2022 is expected to reach 5% of GDP, an increase from 4.1% in 2021. Moreover, public sector debt levels have continued to rise. This contributed to the decision of such countries as Nigeria, Senegal, Côte d'Ivoire, and Kenya to delay their issuance of Eurobonds in early 2022.

Slower GDP growth in 2023, together with lower commodity-related income windfalls, will further slow efforts to decrease debt levels. Furthermore, higher debt servicing costs will damage fiscal balances following the steep depreciation of local currencies against the US dollar and sharp increases in local government bond yields.

Debt restructuring and reprofiling is likely in low-income and debt distressed countries during 2023, although disorderly debt default is deemed unlikely. Countries such as Ghana, Nigeria, Malawi, and Mozambique have a high—if not imminent—risk of debt restructuring.

Social stability and security

Militancy and elections remain major sources of instability across the region.

In East Africa, the Ethiopian government and the Tigray People's Liberation Front—the dominant party of the insurgent Government of Tigray—signed a cessation of hostilities agreement in November 2022. The commencement of heavy weaponry disarmament by the insurgent Tigray Defence Forces (TDF) indicates and progress towards the formation of an interim administration for Tigray make continued commitment to the peace process there likely, and re-escalation to conventional conflict unlikely.

In Nigeria, President Muhammadu Buhari is stepping down after two terms. Newly elected President Bola Tinubu will be confronted by numerous and urgent challenges. These include Nigeria's unsustainable fiscal position, with more than half the 2023 budget to be financed with new debt, and its precarious security situation.

Decision-making capacity in countries such as Angola, Mozambique, Senegal, and South Africa may be constrained by contentious elections, political infighting, and popular protests driven by socioeconomic factors. Other coastal West African countries, particularly Benin and Togo but also Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana, have a heightened risk of jihadist attacks by groups that are taking advantage of continued instability in Mali and Burkina Faso to move further south.

Rwanda is further building its reputation as a key regional partner for Western countries, with military deployments aimed at promoting their energy (Mozambique) and security (Benin) priorities, and "offshore" migrant processing agreements (United Kingdom and Denmark) aimed at enhancing their regional political profile.

Energy sustainability and security

In November, Egypt hosted COP27, which focused a spotlight on how African countries relate to sustainability concerns.

One of the most important topics at the event was climate finance for developing countries. It is estimated that between 2020 and 2030, African countries require in aggregate $280 billion annually to realistically implement their Paris Agreement nationally determined contributions. Between 2016 and 2020, however, only around $20 billion was provided to Africa in total.

Given this, African countries are expected to continue advocating for greater levels of climate finance, especially grants and concessional loans, which do not exacerbate debt service or fiscal sustainability risks. Countries may also pressure finance providers to follow in the example of South Africa's $8.5 billion Just Energy Transition Partnership.

African countries are also increasingly likely to seek ways to monetize financial instruments such as carbon credits, green-, social-, blue- and sustainable bonds or debt-for-nature swaps. In these areas, Gabon and Seychelles lead the way in Africa and globally.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.