Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

1 May, 2018

Banking & Financial Services

By Nathan Stovall and Chris Vanderpool

Community bank balance sheets stand in even stronger position than their larger counterparts to comply with a new accounting provision that will change the way banks reserve for loan losses.

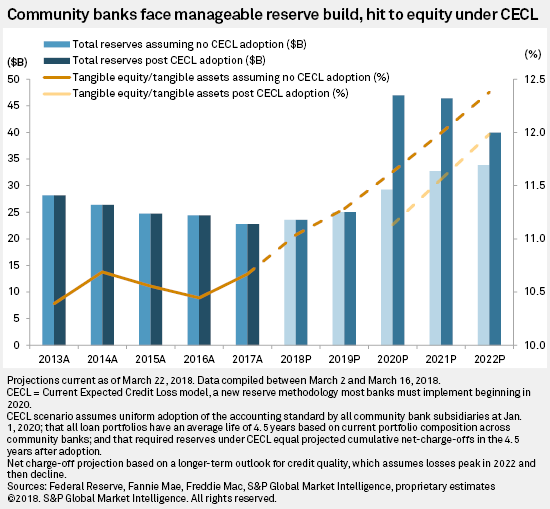

Community bankers have been some of the most vocal market participants decrying the complexity of complying with the Current Expected Credit Loss model, or CECL. CECL will require banks to set aside reserves for lifetime expected losses on the day of loan origination. While the adoption will result in a sizable capital hit for community banks, we do not expect the balance sheet impact to be as severe for smaller institutions, as they continue to report superior credit quality.

S&P Global Market Intelligence estimated the capital impact to community banks as part of our updated five-year outlook for institutions with less than $10 billion in assets. We found that pulling forward expected loan losses could allow community banks to earn their way through a downturn, which could begin when banks adopt the methodology in 2020. Community banks are expected to respond to the capital charge, however, by raising prices on loans and slowing their balance sheet expansion. That in turn should allow the institutions to record even smaller increases in deposit costs.

CECL's capital hit less punitive for community banks

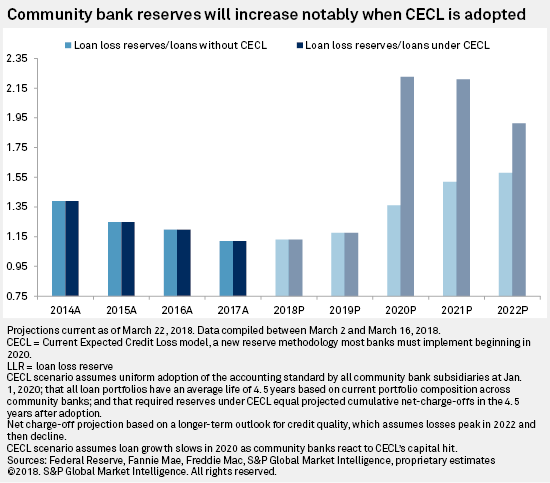

CECL becomes effective for many institutions in 2020 and will mark a considerable shift in practice. Banks currently set aside reserves over time, whereas the new provision requires them to substantially increase their allowance for loan losses on the date of adoption. If that adjustment exceeds retained earnings, the change will result in a capital hit to the industry.

Community banks' tangible equity-to-tangible assets ratio could fall to 11.13% in 2020, assuming uniform adoption of CECL by all community banking subsidiaries at that time. That level is 50 basis points below projected capital in our baseline scenario, which assumes that banks continue operating under the existing incurred loss model. We believe the banking industry in aggregate would experience a far larger hit to capital due to CECL, with its tangible equity-to-tangible assets ratio falling to 8.25%, or 127 basis points lower than our baseline scenario.

Our analysis was based in part on a white paper co-authored by Joshua Siegel and Ethan Heisler that estimated CECL's impact on banks with less than $50 billion in assets. Siegel is the managing partner and CEO of StoneCastle Partners LLC, and Heisler is president of the Bank Treasury Newsletter, which highlights industry trends for bank treasurers. They assumed that loans were originated at year-end and that the required reserve build would equal cumulative net charge-offs in the five years after adoption.

We assume that CECL reserves would match charge-offs over the life of loans, estimated at 4.5 years for community banks, beginning in 2020, and accordingly projected that the required reserve build for community banks could reach $17.7 billion, or 1.6x the level of reserves projected under the incurred loss model.

Major CECL scenario assumptions

-Loan portfolios have a weighted average life of 4.5 years, based on the current loan composition across community banks.

-Reserves equal cumulative net charge-offs in the 4.5 years after adoption.

-All community bank subsidiaries uniformly adopt the provision at January 1, 2020.

-Average life of loans: mortgages seven years; multi-family loans six years; commercial and industrial loans 1.6 years; commercial real estate credits 3.8 years; and consumer loans two years.

-Average life of loans rises modestly over the next few years, continuing a trend exhibited by community banks in recent quarters as institutions reach further out the yield curve to bolster income.

The projected reserve build assumes that credit quality will begin to deteriorate more significantly in 2020, after economic growth proves too weak for institutions to lever the additional capital created by tax reform, resulting in heightened competition for loans. Banks will likely compete on price, but some institutions likely will loosen loan structures. That would follow two consecutive years of more banks easing rather than tightening underwriting standards, according to the OCC.

Competition could pick up just as regulatory pressures ease. The Trump administration and Republican-controlled Congress have pushed to soften many rules passed in the aftermath of the credit crisis, and the rolling back of regulations could invite further easing of underwriting standards. This would occur as interest rates increase, leading to more expensive debt service and pushing some borrowers to the brink.

Even with those headwinds, community banks should once again maintain stronger credit quality than their larger counterparts. Community banks have greater exposure to real estate lending than larger institutions, and while valuations have risen considerably since the depths of the credit crisis, there are reasons to believe that smaller institutions' credit quality will hold up far better through the next downturn. The lack of a housing bubble and massive overbuilding in the residential real estate sector as well as heightened regulatory scrutiny over elevated commercial real estate lending concentrations should help prevent history from repeating itself.

We expect community bank net charge-offs to eventually peak at 0.79% of average loans in 2022 under the CECL scenario. Projected losses are considerably higher than current levels, but peak losses are projected to be about half the level witnessed during the Great Recession.

As CECL comes online, community banks expected to rein in growth

CECL could leave community banks better prepared for a downturn, assuming the credit cycle bottoms two years after the adoption of the provision. Since CECL requires banks to reserve for the full life of loans, much of the required reserves in future years will have already been set aside in 2020. That means additional increases in reserves would be minimal in 2021 and 2022, resulting in far lower provisions for loan losses than would have been recorded under the current reserve methodology, and accordingly, higher returns.

Community bank returns will be further supported by higher rates on newly originated loans, particularly longer-dated real estate credits that will require a larger reserve build under CECL. We have incorporated that change into our CECL scenario and assumed the community bank group’s loan yield will be a few basis points higher after adoption.

We assumed that loan growth will be slower than it would have otherwise been as banks with thinner capital ratios hoard cash and work to rebuild their capital bases. We also assumed that community banks' deposit costs would not increase quite as quickly given that their funding needs would not be as great.

If the cycle does bottom after CECL's adoption, the new accounting provision might work as intended since community banks will have built reserves well ahead of a downturn. This, of course, assumes that community banks will adopt our outlook for credit quality. Some institutions might rely on broader economic models and historical information when projecting losses for years beyond CECL's implementation date, which could result in smaller increases in reserves at 2020.

If institutions' assumptions are less severe, but net charge-offs reach our expected levels, community banks will need to continue building their reserves as losses peak, leaving them on weaker ground when the cycle turns.

Scope and methodology

Scope and methodology

S&P Global Market Intelligence analyzed nearly 10,000 banking subsidiaries, covering the core U.S. banking industry from 2005 through 2017. The analysis includes all commercial and savings banks and savings and loan associations, including historical institutions as long as they were still considered current at the end of a given year. It excludes several hundred institutions that hold bank charters but do not principally engage in banking activities, among them industrial banks, nondepository trusts and cooperative banks. The analysis divided the industry into five asset groups to see which institutions have changed the most, using key regulatory thresholds to define the separation. The examination looked at banks with assets of $250 billion or more, $50 billion to $250 billion, $10 billion to $50 billion, $1 billion to $10 billion, and $1 billion and below.

The analysis looked back more than a decade to help inform projected results for the banking industry by examining long-term performance over periods outside the peak of the asset bubble from 2006 to 2007. S&P Global Market Intelligence has created a model that projects the balance sheet and income statement of the entire industry and allows for different growth assumptions from one year to the next.

The outlook is based on management commentary, discussions with industry sources, regression analysis, and asset and liability repricing data disclosed in banks' quarterly call reports. While taking into consideration historical growth rates, the analysis often excludes the significant volatility experienced in the years around the credit crisis.

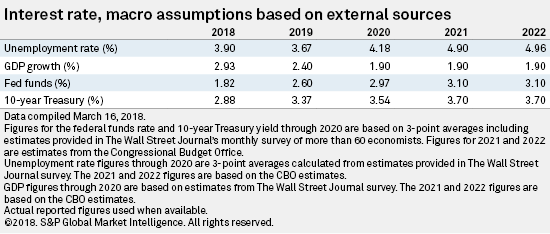

The projections assume future Fed funds rates and 10-year Treasury yields based on a monthly survey of more than 60 economists conducted by The Wall Street Journal. Interest rate assumptions for 2021 and 2022 are based on the Congressional Budget Office's annual outlook. S&P Global Market Intelligence does not forecast changes in interest rates or macroeconomic indicators and aims to project what the banking industry will look like if the future holds what most economic observers expect.

The outlook is subject to change, perhaps materially, based on adjustments to the consensus expectations for interest rates, unemployment and economic growth. The projections can be updated or revised at any time as developments warrant, particularly when material changes occur.