Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

18 Jul, 2016 | 13:00

Highlights

China's NPL problem has been understated and the NPL ratio would be higher if Western accounting norms were applied. The situation will get worse with a slowing economy and supply-side reform…

The potential NPL ratio is higher if we factor in the bad debts from shadow credit…

While official bad-debt numbers in China are rising fast as its economy weakens, risks in the country's banking system probably remain greatly understated.

With China's GDP growing at the slowest pace in more than two decades, the aggregate nonperforming loan ratio of the nation's commercial banking sector rose to 1.81% at the end of June, the highest since the global financial crisis, from 1.75% three months earlier, the China Banking Regulatory Commission said July 15.

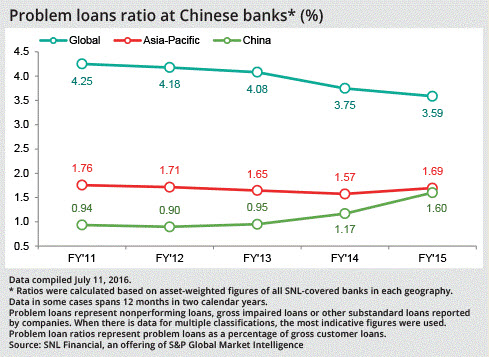

China's rising problem loan ratio is still low by global standards — at the end of 2015, when the metric for SNL Financial-covered Chinese banks rose to an asset-weighted average of 1.60% from 1.17% a year earlier, it was still far below the worldwide level of 3.59%.

Now that signs of troubles abound in China, such as idle capacity in some industries, questions are arising about whether data from lenders and the government reliably illustrates how well-equipped the nation's banking system is to face any bad-debt crisis. Under one extreme scenario, mapped out by independent brokerage and investment group CLSA, banks would need new capital equal to more than 15% of China's GDP, the world's second-largest in nominal terms.

Some outside estimates based on corporate profitability suggest that the situation is far more alarming than indicated by official figures, which can be skewed because of differences in the way NPLs are recognized in China and elsewhere. Further complicating matters, shadow banking, which is hard to capture fully in China, is rampant in the country.

"The official NPL ratio at commercial banks is definitely an underestimate," Chen Shujin, a banking analyst at DBS Vickers (Hong Kong), said in an interview.

For the treatment of bad debt, the standard international practice is to classify loans as nonperforming if they are overdue for 90 days or more, according to CLSA. In China, banks tend to delay the recognition of NPLs longer than the norm, since most corporate loans are made to state-owned entities, with the government effectively acting as the ultimate guarantor of their debt, CLSA analysts Francis Cheung and Alec So said in a May report.

"China's NPL problem has been understated and the NPL ratio would be higher if Western accounting norms were applied. The situation will get worse with a slowing economy and supply-side reform," they wrote.

CLSA estimates that China's NPL ratio could be as high as 19%, based on an analysis of financials of listed companies for 2015. The firm arrived at that worst-case scenario by expanding the scope of NPLs to any debt held by companies with insufficient EBITDA to cover two times interest expenses.

CLSA then used the proportion of loans held by the troubled businesses as a proxy for the status of all commercial bank credit, an estimated 80% of which has been extended to corporates including nonlisted firms.

In its April Global Financial Stability Report, the IMF used a similar approach to assess China's banking system. Just counting companies whose liabilities exceed profit by any margins, the multilateral lender cautioned that 15.5% of all corporate loans in China are at risk.

Any such figure is "a very high NPL ratio," Cheung at CLSA said in an interview. "It, of course, implies a big risk."

Shadowy NPLs

Further muddying the waters in determining the true extent of China's bad-debt problem is shadow banking, which is not covered by the estimated NPL ratios from CLSA and the IMF.

"The potential NPL ratio is higher if we factor in the bad debts from shadow credit," Cheung said.

With the broader economy slowing, Chinese companies, especially those in sectors with excess capacity, such as steel and cement, are having a harder time obtaining credit through official channels. As a result, such borrowers are increasingly turning to informal financing.

Commercial banks in China, particularly small and midsized ones, are actively lending under the radar through complex arrangements to skirt credit rules. Shadow loans are estimated to have ballooned to 21 trillion yuan, about 10% of total bank assets, as of the end of the first quarter from 6 trillion yuan as of Dec. 31, 2012, growing at a compound annual rate of 46%, Deutsche Bank estimates show.In a fast-growing type of shadow lending, a bank uses an intermediary such as a trust company, a brokerage, an insurer or a mutual fund to set up a special purpose vehicle. That entity makes a loan to an unhealthy company and uses it as the underlying asset for an investment product that the same bank purchases with its own funds. The bank then books the holding as an investment receivable, which carries lower risk weightings than a credit asset and is not subject to the domestic reserve requirement for loans.

|

“The official NPL ratio at commercial banks is definitely an underestimate” |

Lending disguised as interbank transactions is another type of financing lumped into investment receivables, which can also include holdings not tied to shadow banking.

Loans appearing as investment receivables in total surged more than 15-fold to make up almost 70% of banks' shadow financing as of March 31 from the end of 2012, according to Deutsche Bank.

Evergrowing Bank Co. Ltd., the 20th-biggest SNL-covered commercial bank by assets in China, is among institutions fueling that growth. Its investment receivables, which have surpassed proper loans, surged more than 10-fold in the four years through Dec. 31, 2015. The company said last year that all of its investment receivables are practically tied to shadow credit, according to Reuters. Attempts to contact the bank for comment by telephone were unsuccessful.

Postal Savings Bank of China Co. Ltd., the sixth largest, has warned investors about risks associated with shadow assets as it prepares for a Hong Kong IPO. The lender's interbank investments jumped to 12.4% of total assets as of the end of the first quarter from 2.7% in December 2013, the company said in a draft prospectus filed with the Hong Kong stock exchange in July.

"We may not be able to recover the principal of and interest on these investments in special purpose vehicles if the financial condition of the ultimate borrowers materially deteriorates," the bank said.

Other forms of shadow banking in China include funds channeled to businesses through sales of off-balance-sheet wealth management products, which are offered by banks to ordinary investors as high-yield alternatives to deposits.

A lack of comprehensive data makes it difficult to get the full scope of how much of shadow banking credit in China is turning bad. If a 15% NPL ratio is applied, CLSA estimates that there is 4.6 trillion yuan of soured debt in that space, or 4% of GDP. Using a similar top-down approach, the IMF calculated that losses from shadow products for banks could be US$98 billion, or about 656 billion yuan.

Doomsday scenarios

The cost of a full-blown bad-debt crisis in China, however unlikely, could be exponential. Under CLSA's most-daunting scenario, if 20% of formal loans go bad at the same time, banks will need new capital amounting to 6.6 years of profit, or 15.6% of GDP, even if they all cut provisions to 100% of NPLs from a required 150% and lower Tier 1 capital ratios to 8.5%, the brokerage said in its May report.

With a bad-debt coverage ratio at the regulatory minimum, 4.1% is the highest NPL level China's banking sector can withstand without fresh capital, CLSA said.

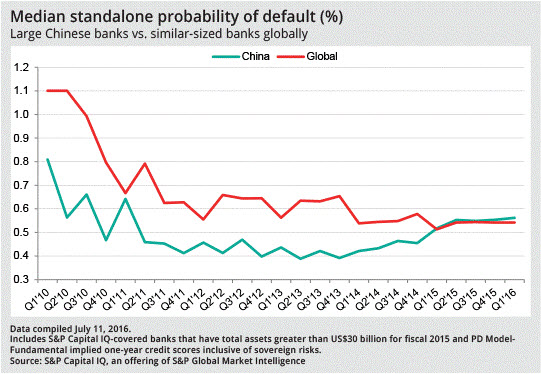

Small banks that are less likely to receive government support than large institutions in times of distress could be particularly vulnerable. Without state aid, the one-year probability of default for a typical small bank in China would jump to 4.3% from 0.5%, if it had a 15% NPL ratio, and if all soured credit assets were written off, according to an S&P Global Market Intelligence analysis.

For now, such situations remain a remote possibility. The chances of a company defaulting immediately after making a loss for one year, the timeframe used by CLSA and the IMF, are low, Chen said.

Also, if stress in the banking system reaches a dangerous level, the government is highly likely to come to its rescue. The state has been taking steps to help banks deal with NPLs as well, such as creating asset management companies that buy bad debt and allowing select lenders to securitize soured credit.

The median standalone probability of default for Chinese banks with more than US$30 billion in assets was 0.57% at the end of March, compared to 0.54% for similarly sized banks worldwide, according to S&P Capital IQ data.

Yet, Beijing's top focus is still on economic expansion, which involves companies taking on more debt. The government has set its 2016 growth target at a range of 6.5% to 7%, compared to 6.9% in the prior year. It also aims to boost so-called total social financing, the broadest measure of credit in China, including some shadow banking instruments, by 13%. The goals indicate "pro-growth and less reform," CLSA said.

That bias means bad-debt risks are continuing to loom large for Chinese banks.

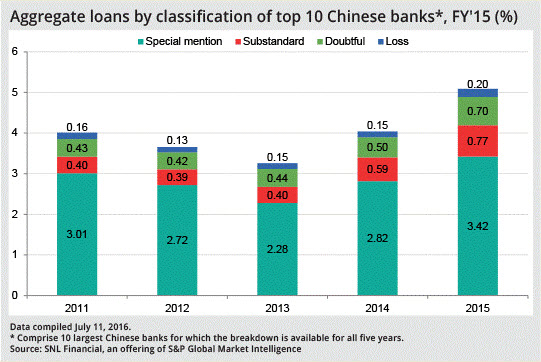

NPLs at the 20 largest Chinese banks swelled 107.32% in the two years to the end of 2015, according to SNL data. In addition, what they reported as special mention loans — loans overdue for less than three months and backed by collateral — increased 83.64% over the same period.

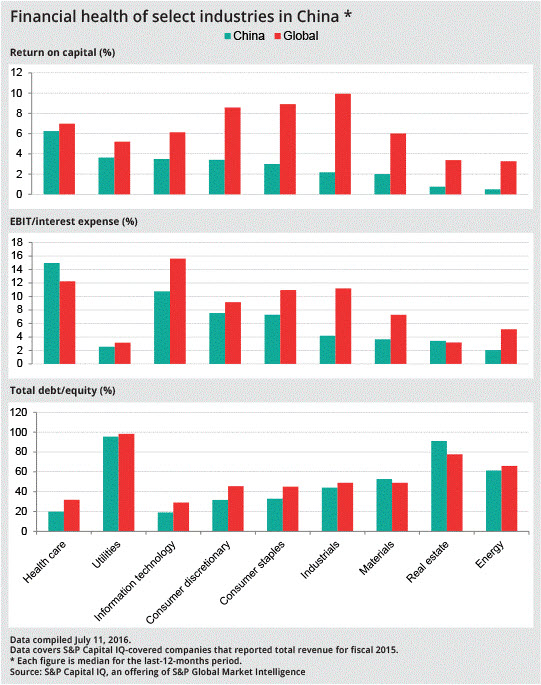

Companies in China are less leveraged than their peers in other countries, but they have weaker profitability, with their overall return on capital across nine key industries trailing the global level, an S&P Global Market Intelligence analysis shows.

Energy bad debt

By that measure, energy is the weakest sector in China. Energy-related companies earned a median return on capital of 0.51% in their latest annual reporting periods, compared to 3.27% globally. The industry's median EBIT-interest expense ratio for the 12 months was 2.05%, less than half the 5.16% worldwide.

Stress in the sector is showing up on the books of some lenders.

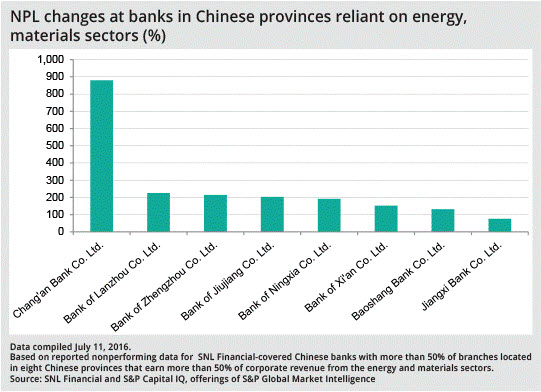

Take Chang'an Bank Co. Ltd. The lender is based in the capital of Shaanxi province, where the energy industry accounts for more than 60% of corporate revenue, and all of its branches are in that region. NPLs at the bank ballooned more than ninefold at the end of 2015 from two years earlier, according to SNL and S&P Capital IQ data. Phone calls to the lender's headquarters to seek comment went unanswered.

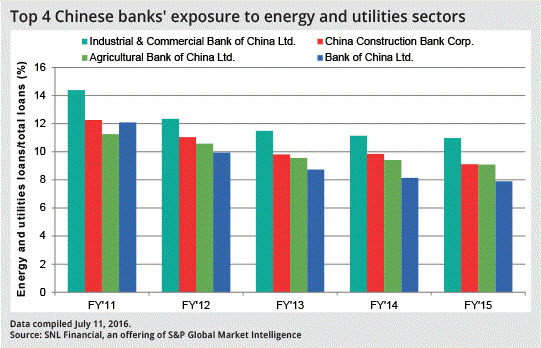

The four largest national banks, meanwhile, reduced their exposure to energy companies from 2011 to 2015. At Bank of China Ltd., credit to energy and utilities firms shrank to 7.9% of total loans at the end of 2015 from 12.08% four years earlier, according to SNL data. Industrial & Commercial Bank of China Ltd. cut the figure to 10.96% from 14.38%.

Chinese banks may be turning cautious about lending to risky borrowers, but their asset quality will likely continue to deteriorate. Their reported NPL ratios will climb as defaults on existing loans gradually surface, said Leon Qi, head of research for financial institutions in Greater China at Daiwa Capital Markets. It could take as long as a year before a loan becomes nonperforming, he noted.

"The ability of many Chinese listed firms to service their debt obligations is eroding, with higher debt and declining earnings capacity," the IMF said in its April report. "Structural weakness and cyclical stresses are becoming more evident."