Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Blog — 27 Jul, 2021

Introduction

For years, a debate has been raging: Which is the cheapest option, the public or private cloud? As with most things, the answer isn't binary, and depends on a variety of things. But the hyperscalers are in a position to squeeze costs more than most, and may have an upper hand in the future. How should smaller service providers and tech vendors face this challenge?

The 451 Take

As a longer-term strategy, private cloud service providers and vendors should focus on two key messages: integration of the private cloud in a hybrid strategy (particularly with regard to a unified consumption model), and the value of a private cloud in a regulated and compliant world. At scale today, private clouds can be cheaper, but as time goes on, it will be increasingly difficult for private cloud deployments to be cheaper than public clouds because of economies of scale that require vast capital and aggregated demand that aren't accessible to enterprises. There is no need to fret about this inevitability. The short- and long-term value of the private cloud is as a vital component in hybrid cloud and multicloud deployments, and when regulation, compliance and peace of mind are worth paying a premium for.

The great debate will reach a conclusion

The great debate over public vs. private clouds has gone on for a decade. Established tech vendors, concerned at seeing workloads moving to new disruptive cloud providers, have often led the argument that private clouds can be cheaper than public clouds. In fact, for a number of years, 451 Research's Cloud Price Index found this to be the case: at a certain level of scale, private cloud resources can be cheaper than public cloud.

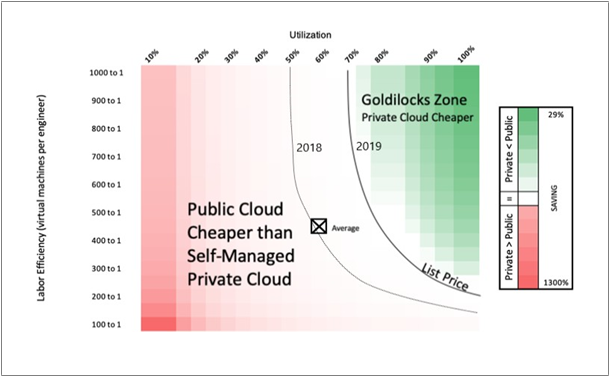

Figure 1: Breakeven Heatmap of On-Premises Cloud vs. Public Cloud

Source: 451 Research Cloud Price Index: The Economics of Private Cloud Colors show savings achieved in that combination of labor efficiency and utilization. Average shows average utilization and labor efficiency for enterprises in 2019.

This has led some to talk of 'repatriation' – i.e., the movement of public cloud workloads back to private clouds as deployments grow. Sometimes this does take place, the classic case being Dropbox, which moved from AWS to its own servers in 2016, and saved $75m over two years. But how many other cases of such large-scale migrations have taken place since then? The fact that Dropbox's migration was five years ago and is still referenced today shows similar examples are few and far between.

The COVID-19 outbreak certainly hasn't validated the repatriation hypothesis – 19% of enterprises have accelerated public cloud migration, while just 2% are moving away from public clouds, according to our Voice of the Enterprise: Cloud, Hosting & Managed Services, Vendor Evaluations - Quarterly Advisory Report. Repatriation does happen, and when it does, enterprises report they have made great savings, but these are edge cases rather than standard occurrences.

Hyperscalers are incentivized to squeeze costs

There are some technological improvements that, over time, will benefit buyers of both public and private clouds. Moore's Law, for example, should mean more workloads can be squeezed on a server, reducing unit costs for hardware, as well as electricity and space. For server and chip manufacturers, it's worth investing in increasing capacity and lowering the cost of their products because the investment will pay off due to their large market shares.

This increased capability and lower cost is passed on to enterprises and smaller service providers that, to some degree, get more for less (or at least the same). The buyer benefits from the economies of scale of the manufacturer. But the enterprise has limited economies of scale of its own. Even massive companies have limited economies of scale for infrastructure because they are

focusing on their own demands, rather than aggregating demand from multiple entities. Obviously, aggregated infrastructure demand across multiple enterprises is going to be bigger than the demand of a single enterprise.

Hyperscalers take aggregated demand to the nth degree. They are the brokers of infrastructure across hundreds of thousands of entities. They are in a position to invest huge amounts on squeezing every cost across the network, datacenter, hardware, software and labor force.

The hyperscaler is able to squeeze infrastructure costs more than is imaginable for an enterprise: building its own supply chain with its own standardized server design, architecting a state-of-the-art datacenter facility with low waste, building renewable energy sources, leveraging longer-term contracts to purchase low-cost power, and automating at every opportunity. The hyperscalers are always going to be in a strong capital position, where it is financially viable to research and implement cost-saving innovations, even if they only make a tiny difference. Others just don't have the economies of scale to make such innovations worthwhile, or even feasible.

Private clouds can be cheaper at scale, and this will always be the case. What will change over time is this definition of scale. The hyperscalers' cost base is inevitably going to decline faster than others because it has the economy-of-scale advantage as a result of aggregated demand. As the hyperscalers grow bigger, their ability to squeeze costs (and the benefit in doing so) will grow bigger than can be matched by any enterprise datacenter, colocation facility, service provider or tech vendor.

And even if this wasn't the case, the hyperscalers have enough margin to take the hit by slashing margins, and still be comfortably profitable. AWS, for example, reported $13.5bn in operating profits for 2020, an operating margin of 30% on its revenue of over $45.3bn. We don't know the figure for its gross margin, but it's clear AWS is making a fair bit of cash from every vCPU and gigabyte it sells.

If AWS really did face substantial price pressure from repatriation, it has lots of margin wriggle room to cut its prices. Its constant growth in revenue (up 30% 2019 to 2020) would somewhat offset this price cut, although obviously, growth would not be as expected by its shareholders. The point is, it could survive quite comfortably if it had to take a hammer to its prices to quell the so-called repatriation from public clouds. And of course, it could take this step at any time.

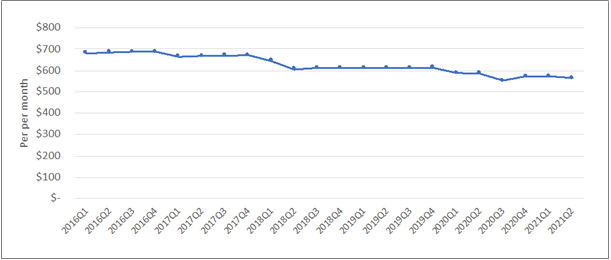

AWS doesn't have to take this step just yet (if ever). The hyperscalers have cut prices over the last year (see Figure 2), but there is no evidence this is impacting profits – it continues to innovate on squeezing costs. The same applies to Google and Microsoft. They are in a position to cut costs more effectively than others, and still have the backup option of cutting margins if need be. Vendors and service providers could cut their prices too, but they aren't in a position to squeeze costs like a hyperscaler, nor do they have significant margin wiggle room. It will be increasingly difficult for private clouds to compete with public clouds on cost, as time goes on.

Figure 2: Cloud Price Index Large Basket Benchmark for US-East

Source: 451 Research Public Cloud Price Index: Q2 2021 Country Benchmarks and Tools

As the heatmap in Figure 1 shows, the breakeven shifted right from 2018 to 2019 (we discontinued this study in 2020 due to lack of reliable data suitable to make conclusions). From 2018 to 2019, the 'scale' at which enterprises needed to operate (in terms of labor efficiency and utilization) increased. In other words, it became effectively harder for enterprises to make private clouds cost less than public clouds.

Who cares anyway?

Cloud costs can be substantial. And if they are substantial enough, they can of course significantly impact profitability and even market capitalization. So it makes sense to squeeze costs where you can. But to squeeze costs to the detriment of flexibility defeats the point of the cloud. To view the cloud purely as a cost-saving measure does away with all the value it brings.

The whole point of the cloud is to enable rapid scalability, to allow organizations to grow and shrink applications to changing demands with no notification, paying only for the resources consumed. This allows businesses to grow capacity when needed so opportunities aren't missed, to quickly enter new markets, to change business models and launch new products, and to take risks and experiment.

This ability was never so important as it was during the COVID-19 pandemic. As we increasingly relied on web applications for education, shopping, health, home working and entertainment – cloud scalability enabled it. Although new private cloud pay-as-you-go models are significantly aiding scalability and flexibility, public clouds have an edge here, in that vast capacity is accessible in minutes to anyone with a credit card.

Sure, a one-time increase in operating profits because of cost savings as the result of repatriation is probably going to attract attention from investors, by short-term kowtowing to shareholders. But is it going to attract as much attention and confidence as smaller increases in revenue and market share over a longer period, as a result of the rapid flexibility enabled by public clouds? For example, by a company being able to gain a first-to-market advantage, or to enter a new region within weeks not years, or being able to pivot its business model rapidly as the result of an unexpected event (like a pandemic).

So is the private cloud doomed?

Absolutely not. In fact, it's the opposite: private clouds are going to be a fundamental part of enterprise deployments, particularly as a key component of hybrid clouds. 59% of enterprises are pursuing a hybrid approach to IT, using both public and private clouds, according to our Voice of the Enterprise: Digital Pulse, Budgets & Outlook 2020 survey. The crucial idea is that there is value in the private cloud, and it doesn't need to be dumbed down to be cheaper than public clouds. This is good news for tech vendors because this argument will be increasingly challenging to make. Below, we discuss two overlapping points.

The value of the private cloud, not the cost

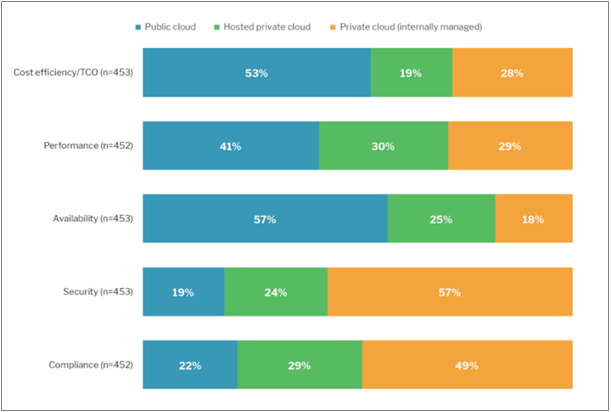

Most enterprises today rate public clouds as the best option for cost-efficiency, performance and availability. But the areas where private clouds stand out are security and compliance. These aren't 'nice to haves' – these are core, business-critical functions with huge implications.

This isn't an area where enterprises want to scrimp, because if things go wrong, the outcome is fines, loss of trust and worse. So why focus on undercutting public clouds? Instead, focus on why your private cloud offering addresses these major concerns and price appropriately, and add on managed services that enhance the inherent security of private clouds, with DevSecOps, monitoring and beyond.

Figure 3: Cloud Venue Perceived as Best for Achieving Outcomes

Source: 451 Research's Voice of the Enterprise: Cloud, Hosting & Managed Services, Budgets & Outlook - Quarterly Advisory Report

Hybrid provides the best of both worlds

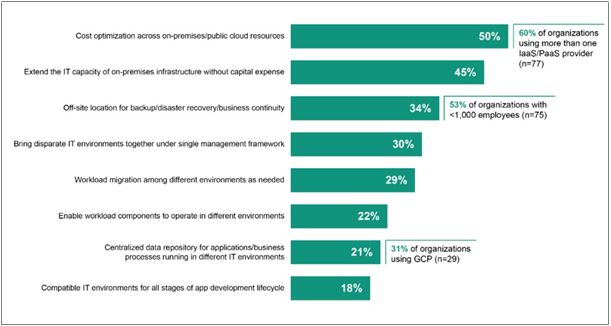

A hybrid approach is rated by 79% of enterprises as very or somewhat important to their choice of vendor (Voice of the Enterprise: Cloud, Hosting & Managed Services, Vendor Evaluations - Quarterly Advisory Report). Cost optimization is the top use case driving this model (see Figure 4).

The reason is twofold. First, a private cloud with a high level of utilization is more likely to meet the 'scale' factor that makes private clouds cheaper than public clouds. The benefit of being able to consume resources from the public clouds should private capacity be reached means the enterprise can fill the whole private cloud without worrying about reaching capacity, which lowers unit costs.

Second, the enterprise can choose which workloads are worth spending more on to protect security and compliance – public clouds for some workloads, and private clouds for workloads that need more assurance (even if it costs more). It is perhaps true that some workloads are being repatriated in a sense – but this isn't a permanent move, it's a more fluid dynamic in a hybrid cloud model.

This fluidity is important. Standardizing on a consumption model across different venues, public and private, elevates a hybrid cloud to be a more flexible, powerful and business-led model compared to public clouds. As shown in Figure 4, regarding avoiding capital being a driver of hybrid cloud, the combination of multiple venues, managed seamlessly together and billed together in a flexible manner, is compelling. And of course, there is an opportunity for managed services and professional services to manage the complex hybrid estate, from maintaining DevOps processes to optimizing for cost and other requirements.

Figure 4: Use Cases Driving Hybrid IT Deployment

Source: 451 Research's Voice of the Enterprise: Cloud, Hosting & Managed Services, Vendor Evaluations - Quarterly Advisory Report

Private clouds are not a commodity, because they are often the venue that drives the most important, business-critical workloads. Vendors and service providers shouldn't have to undercut public clouds. Rather, they should embrace public clouds as working hand-in-hand with private clouds, but with the latter deemed the superior option – in both quality and price.