Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

BLOG — Feb 02, 2023

No one remotely familiar with container shipping, when they first saw the Jan. 25 announcement of the breakup of the 2M alliance, failed to recognize the thunderclap it represented for the industry and supply chains more broadly.

The immediate recognition of seismic significance echoed that of the June 17, 2014 rejection by China of the proposed P3 alliance among Maersk, Mediterranean Shipping Co., and CMA-CGM, a stunning announcement at the time that confirmed China's global influence and led directly to two of those carriers — Maersk and MSC — joining up in the 2M for the past eight years.

This time, it wasn't just that the two largest carriers by deployed capacity had decided to end their alliance in 2025 after 10 years, a development many analysts greeted with minimal surprise given the vastly different styles, cultures, and strategies of the two entities.

Rather, in going their separate ways, it pulled back the curtain on yet another industry era when concentration of market share among the largest carriers had reached an inflection point, such that the largest of them now have the ability to operate at scale outside of a formal alliance. The potential impact on factors such as long-term pricing can't be underestimated.

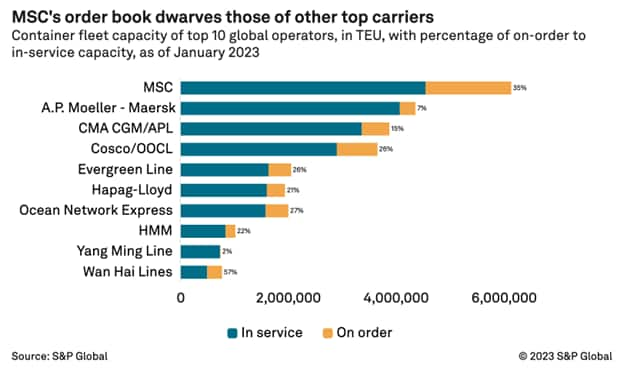

MSC did not say outright that it has no plans to re-join a formal east-west alliance, only that its fleet provides it "with the scale we need for the most comprehensive ocean and short-sea shipping network in the market." Its fleet is already the world's largest and will be further bolstered in the coming years after a spree of new ordering and the largest secondhand tonnage acquisition spree in shipping history, according to Alphaliner.

"Every move that the Swiss-Italian carrier made in the past two years has apparently already been aligned with MSC's new alliance-free strategy," Alphaliner said.

Maersk was clearer in disavowing alliances, with ocean product head Johan Sigsgaard telling the Journal of Commerce, "we have come to the conclusion that a more standalone Maersk network is a better response to the coming years than it was in the past."

But irrespective of what actually happens in two years, the mere possibility that Maersk or MSC could operate alone is a historic change. Contrast this moment to an earlier era, when the industry was far less consolidated and vessel-sharing agreements (VSAs) much more limited in scope.

In that environment, carriers, unlike in the modern alliance era, had little ability to blank sailings in the face of sagging demand, as that could mean up to a two-week gap between sailings, which even back then would have alienated customers. "Flexibility to withdraw ships and services in response particularly to temporary changes [in demand] is limited," then-APL CEO Flemming Jacobs said in the first TPM opening keynote speech in 2001.

Alliances offer scale, agility

As VSAs and later full-fledged alliances evolved, the situation changed: The scale and agility of the combined networks within the 2M, Ocean, and THE alliances evolved to the point where capacity for the first time could be pulled on short notice without catastrophic disruptions to service. That was nothing less than a breakthrough for an industry that had suffered for decades with inadequate returns on capital invested. Even in 2001, Jacobs made reference to "the low return carriers receive for the capital invested," a reality that persisted until the onset of COVID-19.

Mass blanking of capacity was a turning point. It enabled the industry to envision more stable and acceptable returns when prior to that the only lever carriers had in their control to impact the bottom line was cost reduction, often achieved through M&A activity. Alliances allowed the carriers via their partners to build extensive service networks, distribute and lower the costs of deploying tonnage, increase utilization, and engage in capacity management on a scale that had never been seen before. Maritime analyst Linerlytica reported last week that services operated within alliance arrangements enjoyed a 6 percent utilization advantage over independent services.

The breakup of the 2M Alliance and the two largest carriers potentially going it alone throws all of that into question.

It opens the door to a few possibilities. One is that the industry — especially as it enters a potentially extended period of overcapacity — reverts to a competitive scramble for market share, driving down profits and forcing yet another round of M&A, especially if regulators move against alliances. When MSC has taken delivery of all the tonnage it has on order, it will be 30 to 35 percent larger than Maersk, capacity the company will ensure does not go unutilized, according to several analysts. MSC operating on its own "could lead to aggressive pricing," Jefferies noted in a research note.

In that scenario, rate levels would return marginal profits to ocean carriers while carriers would blank sailings when they are forced to in order to stop bleeding cash.

"When there's over-capacity, freight rates will be roughly the cost of providing the service. If the freight rates do not increase, carriers will have to close down services and lay up vessels," said Alan Murphy, CEO of Sea-Intelligence Maritime Analysis. That, in turn, "should lead to freight rates increasing again."

Hardly a convincing recipe for an industry again in search of a profitable formula.

Subscribe now or sign up for a free trial to the Journal of Commerce and gain access to breaking industry news, in-depth analysis, and actionable data for container shipping and international supply chain professionals.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.