Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

S&P Global Offerings

Featured Topics

Featured Products

Events

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

Financial and Market intelligence

Fundamental & Alternative Datasets

Government & Defense

Professional Services

Banking & Capital Markets

Economy & Finance

Energy Transition & Sustainability

Technology & Innovation

Podcasts & Newsletters

BLOG — Dec 05, 2023

An El Niño weather event has been developing in the second half of 2023. El Niño describes a natural phenomenon where the surface temperature of the central Pacific Ocean rises above average. This changes climate patterns and leads to drier conditions in some geographies and wetter conditions in others.

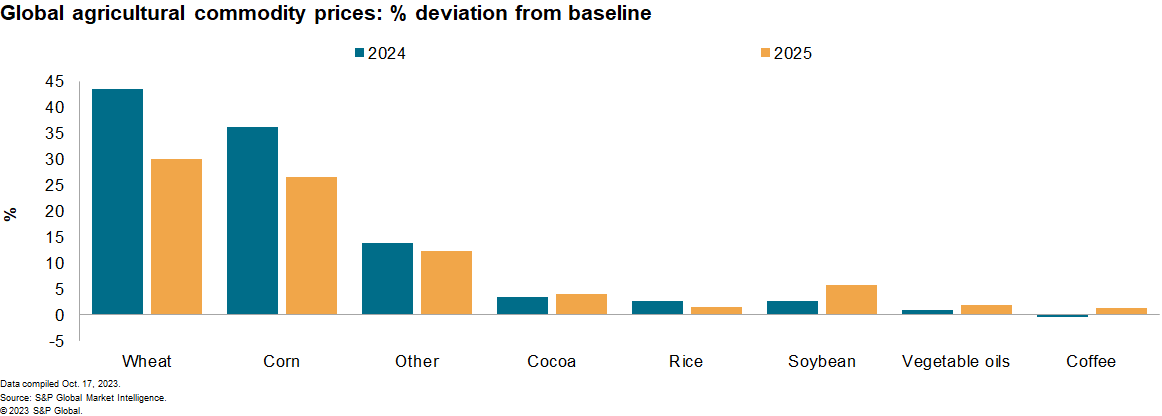

A variety of agricultural commodities will likely come into short supply in the next 12-18 months. Demand for these commodities will evolve as usual, leading to higher prices and affecting industries that rely on these inputs. Electricity generation is also likely to be impacted in areas where hydropower is commonly used, impacting economic activity and manufacturing output.

Although El Niño tends to peak in November to February, the implications for food inflation, fiscal budgets, monetary policy, GDP, and trade last longer. In the countries directly affected by El Niño events, central banks will need to keep policy rates higher for longer to combat more-persistent inflation, keeping government borrowing costs elevated.

Listen to our podcast episode on water stress

Agricultural impact

Palm oil, a water-intensive crop and the world's most consumed vegetable oil, is a particular concern. While both Indonesia and Malaysia hold large palm oil inventories as of September 2023, they are located in Southeast Asia, a region that will face the brunt of El Niño. Weak production growth prospects have the potential to reduce the stocks quickly, eventually creating a shortage. Buyers in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and mainland China boosted palm oil imports throughout the third quarter of 2023 to prepare for potential El Niño-related shortages.

Another water-intensive crop is rice, whose output is largely concentrated in South and Southeast Asia. Concerns about rice shortage have led the government in India to ban exports of non-basmati white rice since late July, while Indonesia is providing its farmers with more incentives to boost domestic production.

One agricultural commodity could see output being spurred by the changing climate patterns in the wake of El Niño: soybeans. This is because the great soybean-growing regions — southern Brazil and northern Argentina in particular — are expected to receive greater-than-average rainfall during the El Niño period.

Water stress will hurt livestock production. Australia and India are major beef producers — India produces beef from water buffaloes — with both countries representing a quarter of global exports.

In sub-Saharan Africa, a severe El Niño phenomenon is likely to cause a 30% contraction in regional agricultural output in 2023-24.

Industrial impact

The segments using more agricultural inputs in their production processes, such as food, wood, fishing, accommodation services and textiles, will more likely suffer from price increases and supply disruptions. The timing of this impact will vary; segments using agriculture as a direct input, such as food, will react more quickly, while those using it as a relatively indirect input, such as textiles, will have a more delayed response.

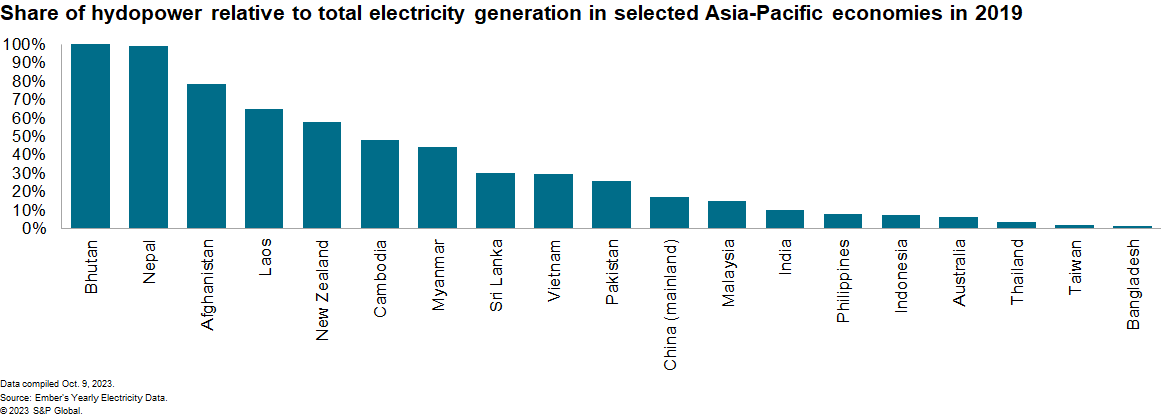

A severe El Niño weather event would likely result in lower overall rainfall in the Asia-Pacific region, and could trigger drought conditions in some nations, affecting hydroelectric power generation, industrial production and mining output. In regions of sub-Saharan Africa where El Niño events tend to bring heavy rainfall, mining production is likely to be negatively impacted.

Manufacturing subsectors such as the making of computer components including semiconductors and chemicals face production risks through water stress and electricity disruption. Out of the Asia-Pacific manufacturing powerhouses at risk from a harsh El Niño, Vietnam and Malaysia stand out as having the highest dependency on hydropower. Significant electricity supply constraints would also be likely in Zambia and Zimbabwe, both of which rely heavily on hydropower.

On the service-sector side, hotter and drier weather will likely hurt tourism activities in the Asia-Pacific region.

Economic impact

In sub-Saharan Africa, El Niño is likely to curtail GDP growth through weak crop production and livestock losses and through reduced hydroelectric power-generation capacity and supply chain disruptions due to infrastructure damage. This is likely to create food-price and generalized inflation. Based on our model's predictions, the average annual inflation rate will rise by 22.7 percentage points in Zimbabwe, 8.3 percentage points in Ethiopia, and 7.3 percentage points in Ghana over 2023-24.

The export of several mineral and other products is likely to be disrupted severely if an El Niño phenomenon results in intense flooding affecting port infrastructure in South Africa and Mozambique on a more severe scale than during the period after 2019.

Countries that are especially vulnerable to this year's El Niño event already have significant debt burdens, large twin (external and fiscal) deficits, and an agricultural sector representing a large share of GDP. Risks are higher for countries that are more exposed to swings in food and energy prices and production, as they often have smaller fiscal buffers, which reduces their ability to cushion the impact of El Niño.

South Africa appears to be the least vulnerable of sub-Saharan African countries exposed to El Niño-induced events this year. However, countries within sub-Saharan Africa with more-fragile economies could lose a significant share of their GDP, with millions of citizens facing food insecurity and displacement. Countries in the region that face the most severe adverse risks in the coming months include Ethiopia, Kenya and Mozambique.

In sub-Saharan Africa countries, food typically comprises around 30% to 40% of spending on consumer goods and services — double the figure for developed economies. Therefore, the severity of the El Niño event will have a significant impact on inflation in sub-Saharan Africa countries, which remains elevated in a number of countries in the region and could push food inflation in affected countries back into double-digit percentages in 2024.

Political risk outlook

Some countries may be more vulnerable to domestic political risks associated with El Niño shocks. In Indonesia, for example, continuing high rice prices would be detrimental to the electability of two presidential candidates associated with current President Joko Widodo — Prabowo Subianto and Ganjar Pranowo — while benefiting Anies Baswedan, who is campaigning as a change candidate.

Listen to our podcast episode about upcoming elections in Asia

Central banks may be forced to keep policy interest rates higher for longer to combat more persistent inflation, increasing the risk of protests largely attributable to the cost of living over the next 12 months in countries such as Ghana and South Africa.

Sri Lanka's economy is still recovering from shortages of foreign exchange reserves and high inflation after securing an IMF bailout package in March 2023. With elections upcoming in 2024, opposition political parties are likely to criticize the current administration for its failure to manage water resources during a severe El Niño. Protests would also be likely from farmers' organizations demanding compensation, with the government's willingness to distribute compensation payment constrained by ongoing austerity measures required to secure further IMF disbursements.

If there are higher-than-usual levels of flooding in parts of Ethiopia and Kenya, this would be likely to generate population displacement, raising the risk of inter-communal violence, particularly in densely populated rural areas.

-With contributions from Lerato Ntuli

Learn more about our data and insights

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.